Cover Image: Nuevo manual del cocinero Criollo, book cover, 1903, Courtesy University of Miami Library, Digital Collections

In the cover image, we see a busty young woman with a tiny waist, a characteristic of female fashion illustrations of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, is depicted in the act of cooking. She is wearing a spotless apron over a fancy striped dress, and is shown in an apparently modern kitchen, stirring her meal at a stove decorated with colourful tiles and surrounded by exotic fruits including pineapples, bananas, papayas and a fish, along with kitchen containers.

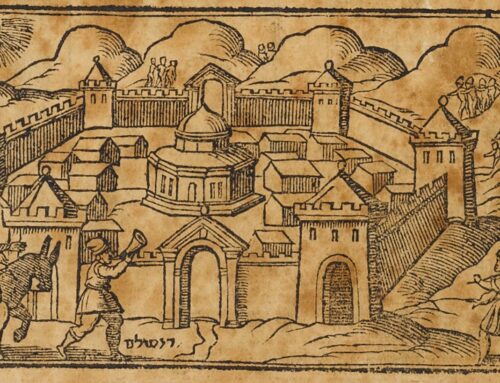

Figure 2: How they cook in Cuba, in The American Kitchen Magazine, 1898, Courtesy of the Hathi Trust Digital Library

This untitled photo portrays a woman and a man in a seemingly clean, modern kitchen. For hygienic reasons, the wood stove area is tiled. The kitchen has five if not six different wood stoves, all of them occupied by a kettle, two pans, a pot and possibly, on the right side, a fish kettle. The vast quantity of stoves and the various metal pots suggest that it was a hotel or a restaurant kitchen. However, in addition to the tools, the dark, grainy picture does not reveal any other key information on either the ingredients used or the dishes prepared.

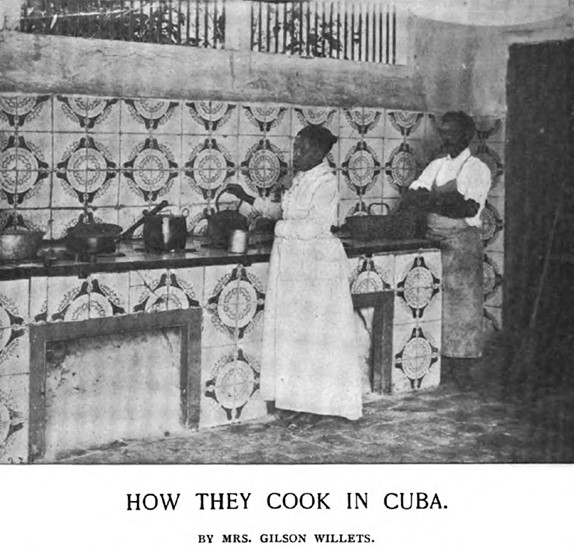

Figure 3: Kitchen and Cuban servants, in Neely’s Panorama of Our New Possessions, 1899, Courtesy of the Hathi Trust Digital Collection

The overexposed picture of Kitchen and Cuban servants shows two women, possibly cooks and/or servants, in an open-air kitchen set in a courtyard as was common for Cuban kitchens at that time. Even though it is not in an enclosed room but outside, on a patio, the kitchen is a modern space, as is shown by the tap and running water. There is a barrel and two buckets, one near the fountain, and the other one in the right hand of one of the cooks or kitchen attendants.

How useful can these three images be for historians? What can we learn about apparently banal processes, such as those which take place in the space of kitchen? Who were the cooks who fed the empires? While giving us the opportunity to shed light on various aspects concerning the circulation of people and ethnicity, we will see that analysis of these pictures raises more questions than the answers they provide, thus paving the way for further investigation in the fields of cultural and social history.

Empires and colonies are the main contexts giving historians the opportunity to examine mass migration, displacement and cultural transfers, and the kitchen is the background against which much of this mixing took place. Within this dynamic physical space, cooks were some of the key agents in this complex modification process (Berti 2021).

In political terms, for almost the whole of the nineteenth century, the United States had expressed its intention to acquire Cuba from Spain, whose empire who ruled over the island until 1898. Also, besides the Ten Years’ War of the decade 1868–1878, the late Spanish colonial period in Cuba was characterized by intense and rapid transformations, chiefly dependent on the main plantation crop – sugar cane. Despite the Spanish hegemony, a good number of US businessmen purchased plantations, established companies and forwarding agencies, provided credit and contributed to the development of a modern, technological communications and transport system. Cuba and its economy gradually became dependent on the United States and less bound to the Spanish Empire. Furthermore, due to the United States’ greater economic power, its proximity to the Cuban coastline, and the milder Cuban weather, starting from the second half of the nineteenth century, a large number of US residents and tourists began to reside for short periods on the island.

The images under discussion were produced when the Cuban slave society came to be abolished (1888), even though the same inequalities continued into the years – 1898 to 1903 – under analysis here.

Within this context, the three pictures of cooks produced by unknown observers that are discussed, compared and contrasted in this article come from a cookery book first published in 1903; the second is an 1898 photograph published in The American Kitchen Magazine; and the third and last one was printed in Neely’s Panorama of Our New Possessions (1899).

Even though there is not any evidence as to the identity of the artist who designed the first image shown, the book cover of the Nuevo manual del cocinero Criollo does give information on the author of the book. It was written by Spaniard José Triay and first published in the Cuban capital, La Havana, in 1903, while the cover shown here is from its 1914 edition.

We know that Triay’s parents moved within the area of the Spanish empire, migrating from Spain to Cuba during the early 1850s, and lived there all their lives. In Cuba, Triay became a writer, poet, journalist and, according to the prologue and the Dos palabras section of the Nuevo manual, he perceived himself and was perceived by his fellow citizens as a gourmet and a cook, too.

Due to the lack of information on the artist of the Nuevo manual book cover, it seems useful to focus on its possible readership, who also had the opportunity to look at its cover, too. Unfortunately, the Prologo written by renowned Cuban medical doctor, Gonzalo Arostegui y del Castillo, does not give a clear idea of the potential public for whom the recipe book was written. However, Arostegui observed that due to the increasing numbers of tourists visiting the island, there needed to be a renewal of Cuban cuisine and its flavours, his wish being for this to become part of a process described as the passage from the “need for food” to the “satisfaction of eating”. Therefore, we can deduce that chefs were the main intended readership, as well as the main observers of the Nuevo Manual book cover.

Besides the colours of the newly adopted Cuban flag in the word Manual, which is of interest for historians researching nations and nationalisms, here we focus on the woman in the picture. The observer of the book cover sees the image of an evidently happy, young female cook working in a safe, clean and pleasant environment.

Even if the ethnic origin of this fictional cook can only be guessed in part by her somatic traits, the main point is that she was not an Afro-American cook. However, neither her complexion nor her eyes and brunette hair allow us to determine her ethnic origin. The most plausible option is that she was an imaginary Spanish cook, and that she could have been from the United States, or from various other European or American countries. In order to avoid conjectures on where she possibly came from, it is also useful to turn to the book’s title, Manual del nuevo cocinero criollo, that is, Manual of the New Creole Cook. “Criollo” and “creole” are respectively the Spanish and English terms to define a person without any specific ethnic origin, or an economy, society, idea, language, culture, dish and much more besides, arising in, growing and changing in the Caribbean, and in the Americas in general, through encounters and entanglements in the colonial spaces. Therefore, the title of the cookery book leads us to suppose that the intention of the anonymous artist was to portray a Creole chef.

In order to acquire a deeper knowledge of the differences between the cook’s desired and imaginary ethnic origins and the reality, it is essential to compare and contrast the book cover of Nuevo Manual with a photograph that appeared in The American Kitchen Magazine published in 1898, just five years before the first appearance of Nuevo Manual and its book cover.

The photograph is taken from Mrs Gilson Willets’ How They Cook in Cuba. While it is clear who Mr Gilson Willets was – a journalist, author and screenwriter – there is scarce information on his wife, the lady who signed herself as Mrs Gilson Willets. The only information we have on her life comes from news published in the New York Times on 24 June 1896, the date that Miss Daisy May Van der Veer married Gilson Willets. At the threshold of the twentieth century, it was still commonplace for women to sign with their husband’s name, to use a pseudonym or to remain anonymous. Nevertheless, there is a coincidence that demonstrates that Mrs Gilson Willets was Daisy May Van der Veer: her article on cooking in Cuba was published in 1898 while Mr Gilson Willets was a journalist there covering the Spanish American War. We guess that Mr Gilson Willets came to Cuba with his wife who, thanks to her stay on the island, also had the opportunity to observe day-to-day local life, including food, cooks and kitchens.

Despite the lack of author and title, we can suppose that the photograph was taken by the same Mr Willets who, in 1898, also provided the pictures for Tennyson Neely’s Neely’s Panorama of Our New Possessions on Cuba, Porto Rico and Philippines. This hypothesis on Mr Willets’ authorship would make sense because the other photo shown here comes from another Neely picture book, Panoramic Views of Cuba, Puerto Rico, Manila and the Philippines, published in 1899 in which his name appears as photographer.

If we now shift our attention from the authorship to the people in the second and third pictures, we have a much clearer idea of their ethnic origins. The woman in the second picture is unquestionably an Afro-American cook while the man could also be Asian, Cuban or from another ethnic origin that was not Anglo-Saxon. Their position in the kitchen space and their non-verbal communication seem to imply that the person in charge of doing the physical work of cooking was the woman, while the man’s crossed arms could be a sign of his supervisory role. Both of them seem to be wearing clean clothes, and the man is also wearing an apron.

Likewise, the third picture shows two Afro-American women in charge of cooking, even though they are not actually cooking in the picture.

Considering that, at the end of the nineteenth century, people still had to pick a pose and maintain it for a few minutes, we should now reflect on the people portrayed. Due to their subaltern role, it is possible that they neither chose their pose and facial expression or their position in the space, nor the clothes that they were wearing. It is also plausible that they were not even cooks but other servants, chosen for various reasons to act this part. Nevertheless, in the conflict between reality and imaginary, we have to point out that observers play a key role in discriminating authenticity from fiction. Therefore, even though the people portrayed in the picture might not have been real cooks, they were credible representatives of that role.

From the style of the kitchens in which the cooks are working and from the quantity of instruments shown, we can also hypothesize that they possibly worked for restaurants, hotels or other institutions in charge of feeding a good number of people.

Another aspect common to the three images is linked to raising interest in modern hygienic cooking habits: they all portray cooks with spotless aprons; the first and second images also show easy-to-clean, tiled kitchens; the hair of both women in the third image is covered by a turban, in the second photograph, the cook’s hair is tied back, while the thick hair of the cook in the first picture is partially loose.

However, the task of comparing and contrasting these three pictures shows its weakness, too. While on one hand there are plenty of resemblances between the portrayed subject, the physical environment, the geographical space and the epoch, there are also some significant dissimilarities.

The first concerns the different means used to represent the cooks in their kitchens: the first picture under examination is a fictional one created by an anonymous artist, while the second and the third are photographs taken by a known author. Photographs should convey a more truthful aspect of life, while paintings are easily the stuff of invention, connected to a desired world far from experience. It goes without saying that images do not say enough about reality, but reveal a lot about the way a society intends to build and represent itself. Banal, everyday pictures can help historians question their sources and discover otherwise hidden aspects of our past. The comparative analysis of three different images of cooks casts light on the society that produced them and reveals complex relationships as well as the ambiguities between reality and imaginary, forcing us to reflect on the meaning of reality itself.

Following this discussion of a fictitious world, the second main difference in the three images shown concerns the ethnicity of the cooks. While on the cover of the cookery book the cook is a Creole woman, both photographs portray Afro-American cooks and kitchen servants.

The analysis of three images of cooks from within the same spatial and time frame raises other questions worthy of future investigation: To what extent can the dissimilarity between the cooks’ ethnicity be inserted in the colonial and imperial context? Did the ethnic differences depend on an idea of building a “whiter” society – so-called blanqueamiento – in the Cuban context? To what extent does the image on the book cover of the Nuevo Manual represent an idealized version of a cook? Were photographs a faithful representation of reality, especially in a context where cameras were slow and snapshots did not exist? What kind of meanings did the observers give to these images? Within which codes did they observe and contextualize the pictures? And finally, to what extent did images contribute to building a desired reality?

References

Ilaria Berti, “In the Kitchen. Slave Agency and African Cuisine in the Caribbean”, in Bartolomé Yun Casalilla, Ilaria Berti and Omar Svriz Wucherer (eds) American Globalization, 1492-1850. Trans-cultural Consumption in Latin America (Abingdon: Routledge, 2021), 169–92.

Christine Folch, “Fine Dining: Race in Prerevolution Cuban Cookbooks”, Latin American Research Review 43, no. 2 (2008): 205–23.

Frank Tennyson Neely, Neely’s Panorama of Our New Possessions (Chicago: F. Tennyson Neely Publisher, 1898).

Frank Tennyson Neely, Neely’s Photographs. Panoramic Views of Cuba, Puerto Rico, Manila and the Philippines (New York: F. Tennyson Neely Publisher, 1899).

Mrs Gilson Willets, “How They Cook in Cuba”, The American Kitchen Magazine, 1898.

José Triay, Nuevo Manual del cocinero Criollo (Habana: La moderna poesía, 1914 [1903]).

Acknowledgments

Ilaria Berti would like to thank funding support from Pablo de Olavide University and the Spanish Ministry of Universities under the program Maria Zambrano funded by the European Next Generation-EU and the kind and valuable comments received by the reviewers.

Biography

Ilaria Berti is a postdoctoral researcher at Pablo de Olavide University, Seville and member of the research project Historia de la Globalización: violencia, negociación e interculturalidad. Her research interests concern food and imperial and colonial history. Her recent publications include The “Offensive” and “Abominable” Spanish Garlic. American and Spanish Empires in Their Fight for Cuba (circa 1840-1880) (2021) and the coedited volume American Globalization, 1492-1850. Trans-cultural Consumption in Latin America (Routledge 2021), while her book, Colonial Recipes in the Nineteenth-Century British and Spanish Caribbean. Food Perceptions and Practice, is in press.