On Wednesday 11 November 1665, Venetian public notary Angelo Maria Piccino received the last will of “Signora Ester Senior consort of Signore Josef Senior, Hebrewess,” penned by herself in the form of a sealed testament and handed to him, in person, in the house of her usual residence in the Ghetto Vecchio of Venice. In this document, which begins with the declaration of faith, “In the name of Adonay, Lord of Hosts, in whom I firmly believe”, Ester alludes to the material losses and childlessness that had affected her marriage; the existence of an absent sister, for whom she professed great love; and a nephew, identified as Manuel Aboab, son of her deceased brother. Among the pious dispositions, she makes bequests to her sister, her nephew, a child she had raised whom she names as “Abranelo”, and some relatives residing in Livorno and Aleppo. She also asks her executor to pay for a lamp which, in her intention, was to burn for a whole year in the holy city of Jerusalem (Fig. 1). The text of the will reflects the existence, around the middle of the seventeenth century, of a Jewish woman who died within the Sephardic community of Venice, but who, despite the company of her husband and a child she had adopted, expresses her feelings of uprootedness, recalling far-away personal ties that had nevertheless been fundamental to her throughout her existence.

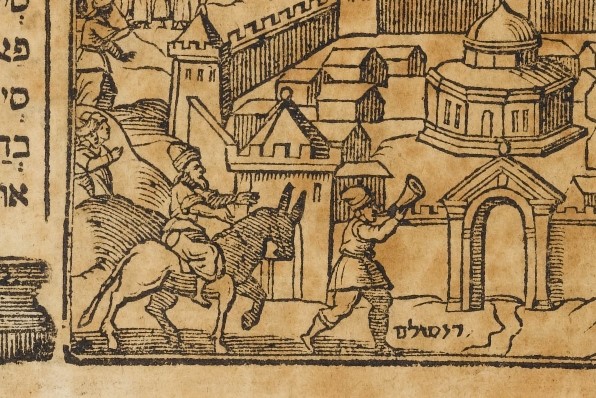

Figure 1: The Holy City of Jerusalem: Passover Haggadah, Venice (1624). Photo courtesy of Ets Haim – Livraria Montezinos (Amsterdam), all rights reserved

Ester Senior was born around 1613 in the city of Lisbon (Portugal) where she was baptized under the Christian name of Ines Henriques. Her parents were the businessman and slave trader Duarte

Dias Henriques and his wife Branca Manoel. This family of New Christians was completed by two siblings: Isabel, and Manoel Henriques, who died leaving a bastard son. All of them descended through the paternal line from Isaac Aboab, a Castilian rabbi, who in the expulsion of 1492 had received authorization from the Portuguese Crown to settle with a group of Jewish families in the city of Porto.

In 1616, in Lisbon, her sister Isabel Henriques married a first cousin named Duarte Coronel Henriques, originally from Baiona in Galicia, who would become his father-in-law’s business partner. In 1627, the family moved to Madrid, centre of the Hispanic monarchy to which the kingdom of Portugal still belonged, and the city where Duarte Dias Henriques died in 1631. On 14 August 1633, Ines Henriques, orphaned of both parents, married her third-degree relative Antonio Enríquez de Rivadeneira, who would later change his name to Josef Senior. After the death of Duarte Coronel Henriques, in 1651 the whole family fled to the free lands in Italy for fear of the Inquisition. The itinerary followed by Isabel Henriques is well known to us thanks to inquisitorial testimonies. She undertook the incognito trip by land from Madrid to Irún (Basque Country), where she crossed the French border to Bayonne, going from there to Marseille, taking a galley to Genoa (Italy), then to Naples, where she joined her sister Ines and her husband. In Naples, they all resided for a while with their relatives, the Counts of Mola. Then the two sisters’ paths diverged: Ester (Ines) continued to Venice with her husband, and Isabel went first to Rome and then to Amsterdam where she would assume the name of Gracia Senior. In Venice and Amsterdam, the sisters would meet relatives who also claimed to be descendants of Rabbi Aboab of Castile.

Gracia Senior alias Isabel Henriques in turn laid down her will in the city of Amsterdam before the notary Peter Padthuysen, on 30 August 1673, eight years after the death of her younger sister. The wills of both sisters have in common the fact that they were written (probably by the testatrixes themselves) in Spanish. This is relevant for several reasons: both sisters were undoubtedly of Portuguese origin and the family’s move to Madrid took place when both were already adults, therefore, Spanish was not necessarily their mother tongue; in the case of Ester’s will, at least, a translation was made into Italian (in the Piccino notary’s volumes there are in total two Spanish and two Italian versions of this document). At the same time, the context of both documents reflects the linguistic plurality of the environment in which the two sisters resided. Both testaments, written in the language of Castile, show the influence of words and linguistic turns from Portuguese and Hebrew, as well as from Italian in the case of the Venetian text. Furthermore, the materials attached by the respective notaries to the testamentary deeds not only included the Italian translation, but also other complementary texts in Italian, Latin and Dutch. All this documentation attests to the complex linguistic environment which the Western Sephardic communities inhabited during the early modern period after the expulsion from the Iberian Peninsula.

Among the close relatives who Gracia (Isabel) met in the Kahal Kadosh of Amsterdam around 1655 was her second cousin Matatya Aboab. Both knew each other very well, because the orphaned Matatya, at that time Manuel Dias Henriques, had grown up in Lisbon in the house of Isabel and Ines’ father, Duarte Dias Henriques. Moreover, before his settlement in Amsterdam, Matatya Aboab had carried out commercial activities in the New World, in Brazil and New Spain (present-day Mexico), thanks to the financial sponsorship of his uncle Duarte Dias Henriques, Angolan slave contractor for the Crown. In Amsterdam, after resuming the public practice of Judaism, Matatya and his family would become active members of the community. In particular, one of Matatya’s sons, Ishack de Matatya Aboab, would be an important sponsor of literary activities, promoting the translation and conservation of texts relevant to the construction of the Western Sephardic Diaspora’s identity. It would be Ishack who would undertake the important task of collecting family information in order to preserve the memory of the Aboabs. A large amount of the documentary material preserved in archives in Amsterdam, Hamburg and other cities of the Diaspora was the product of his work writing, preserving and editing texts relating to family and communal life. The aim of this article is to draw attention to one of these same texts.

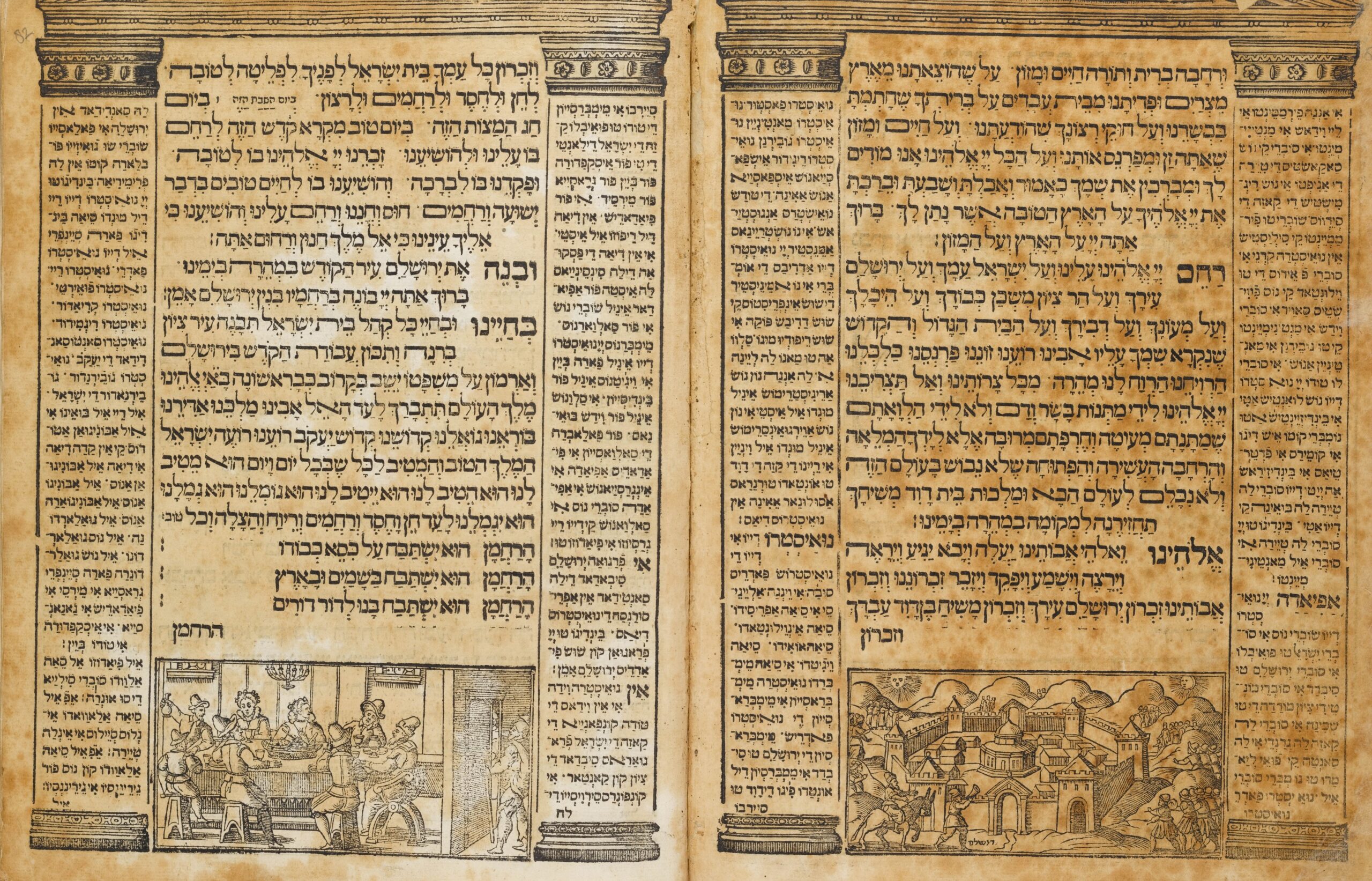

The manuscripts currently preserved in the Ets Haim Bibliotheek – Livraria Montezinos in Amsterdam include one which is indexed as EH 48 A 28. This document consists of a translation of the text of the Passover Haggadah from Hebrew into the Spanish used among the Sephardim of Amsterdam, by Ishack de Matatya Aboab himself with the help of Rabbi Isaac Saruco. The translators’ aim, as they state in the introduction of the work, was to enable the audience to better understand the questions that traditionally have to be asked in Hebrew during the reading of the Passover Seder. In addition, the manuscript EH 48 A 28 also includes the printed edition of the Haggadah which served as a guide for the translators (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Two pages from the Passover Haggadah, Venice (1624). Photo courtesy of Ets Haim – Livraria Montezinos (Amsterdam), all rights reserved.

This is a perfectly preserved exemplar of the famous edition of the Order of the Passover Haggadah (סדר הגדה של פסח) published in Venice in 1629 at the printing house of the Bragadin brothers and including a bilingual Hebrew-Ladino text. This work, which belongs to a publishing series initiated in 1609 by Hebrew publisher Israel ben Daniel Zifroni, would have a long textual and iconographic life within the most diverse Jewish communities.

This edition demonstrates multiple singularities, and in order to adapt its analysis to the original perspective of this collection of essays I have selected the woodcut for the Haggadah of Venice that represents the messianic Jerusalem (Fig. 3).

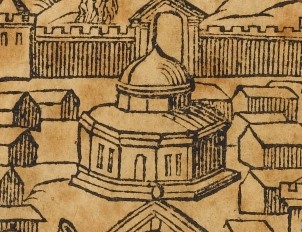

Figure 3: Messianic Jerusalem: Passover Haggadah, Venice (1624). Photo courtesy of Ets Haim – Livraria Montezinos (Amsterdam), all rights reserved.

It is an image that appears towards the end of the text, in the section where the blessing of the second cup of wine takes place, when the Haggadah alludes to the coming of the Messiah and the reconstruction of the destroyed Jerusalem. The engraving shows an idealized Holy City of Jerusalem with the Holy House in the centre (the original temple was actually located on the south side of the city). It is an octagonal building, according to the long tradition that represented it following the current design of the Mosque of the Rock (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Octagonal temple: Passover Haggadah, Venice (1624). Photo courtesy of Ets Haim – Livraria Montezinos (Amsterdam), all rights reserved.

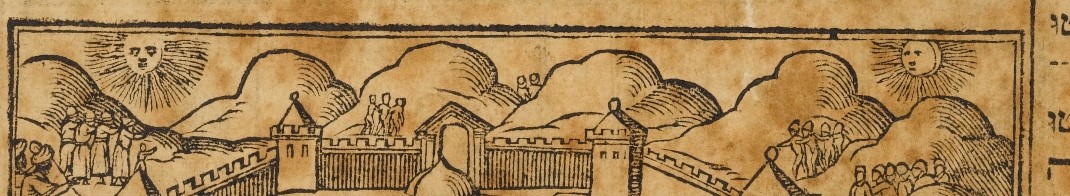

The octagonal model is replicated in the layout of the city walls, with their eight towers or gates. The city is surrounded by mountains, probably referring to Psalm 125:2. Various groups of pilgrims are seen in the mountains, heading towards the city. On the horizon, both the sun and the moon appear above the mountains, in a possible allusion to the day of the Messiah in which the distinction between day and night disappears (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: “The day that is neither day nor night”: Passover Haggadah, Venice (1624). Photo courtesy of Ets Haim – Livraria Montezinos (Amsterdam), all rights reserved.

In the foreground, the Messiah rides on a donkey, preceded by the figure of the prophet Elijah blowing the horn (שופר) to proclaim his triumphal entry (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: The Messiah and the prophet Elijah: Passover Haggadah, Venice (1624). Photo courtesy of Ets Haim – Livraria Montezinos (Amsterdam), all rights reserved.

The scene is loaded with references to biblical passages, rabbinical texts and traditional stories related to Jerusalem, the Messiah and the prophet Elijah. At the same time, it seems evident that, from a formal point of view, the iconographic programme is extremely similar to a second illustration of the same Passover Haggadah of Venice, namely a representation of the ark of the covenant (לַה אַרְקה דֵעל פֵירְמַאמְיֵינְטוֹ) in the Israelites’ camp in the desert of Sinai during the Exodus (Fig. 7).

Figure 7: The camp of the Israelites during the Exodus: Passover Haggadah, Venice (1624). Photo courtesy of Ets Haim – Livraria Montezinos (Amsterdam), all rights reserved.

In this illustration the ark is also in the centre of the image, surrounded by eight Levite priests, and then by the twelve tribes of Israel, organized in four groups (according to the cardinal points) around four banners. The similarity between the two iconographic programmes is confirmed by the presence of the sun and the moon on the horizon of the camp. The only difference is that, in the latter image, four emblematic miracles associated with the divine protection afforded as they wandered in the wilderness appear in the corners.

Both images most probably represent paradigms linked to the situation of the Sephardic Diaspora. This fact is evident in the case of the representation of the community of the people of Israel gathered around the ark in a context of transhumance. The wandering in the desert comes to signify the dispersion of Israel among the nations and the absence of a home (a dwelling place) in the concert of nations. The Sephardic tradition refers to this reality when it speaks of an “exile within the exile” (גלות בתוך גלות). The vision of messianic Jerusalem must also be seen as a kind of inspiration for life in the diaspora, aiming to give encouragement to the communities in their situation of exile.

The messianic longing for the earthly Jerusalem reached its maximum expression among the Western Sephardim during the seventeenth century by means of two distinctive phenomena: the events marking the enthusiasm of the communities of Venice, Livorno and Amsterdam among others (which reached its peak in the same year that Ester Senior wrote her last will) following the appearance of the pseudo-Messiah Sabbatai Zevi, and the constant migration of men and women to the Holy City of Jerusalem. This last human movement, which continued throughout the century as reflected in the records of the various communities, seems inspired by the desire to find a burial place in the valley of Jehoshaphat, facing the Temple of the Lord, in order to participate in the triumphal entry of the Messiah chosen by God at the end of time.

An eloquent example of these experiences appears in the letter that David Senior sent from Jerusalem to his relatives who had remained in the city of Amsterdam on 1 August of the Jewish year 5398 (1638):

… For the desires that your lordships have to know the particularities of this Holy City and our true homeland, since it was the mistress of the people and the joy of the whole earth. And today, because of our sins, it is deserted under the yoke of barbarian peoples, without the use of reason or any policy. And this is well stated in the pasuk [biblical passage] that says “the servants trampled on us,” because they were [servants of] ours and of other nations. And today, as the prophet Lord Nemiau [Nehemiah] says, “we are captives in the land that the God gave to our fathers.” But such are the holiness and privileges with which the Lord of the world endowed it above all other lands, that even though it is subjected and has toiled and almost lost its beauty and abundance, whoever attains this good of being in sight of the sanctuary of the blessed God and kissing its holy blessed stones, invoking the Holiness found in them, is still considered blessed. So that even if He should cast away the holiness of the house of God for a long time, by trusting in the divine mercy of he who taught us this Crown of ours, He will show us and all Israel [the house] raised and built by his holy hand… Today this Holy City is surrounded by stone walls. With very good towers, compared to others in Turkey. It will have a good circuit of half a league, and five very good, large gates. But two, which are closed, one next to the other, are much better; called the gates of piety, they are said to be from ancient times…

David Senior, the author of this letter, was the son of a first cousin of Duarte Dias Henriques, and therefore, a second cousin of Gracia and Ester Senior, as well as of their relatives Matatya and Isaac Aboab. In fact, in the same letter, David mentions Doña Reina, wife of Immanuel Aboab, Duarte’s brother and author of the Nomologia o Discvrsos Legales (Amsterdam, 5389/1629), as his relative. The opening section of the missive vividly alludes to the prevailing Western Sephardim imaginary relating to the Holy City: despite its present precarious state, scarcely reflecting its splendid past, imminent divine intervention is expected, which will change the fate of the city and of all Israel. In this sense, the modest physical appearance of the city is nothing other than a prophecy of the future gathering, thanks to the Messiah’s reign, of the dispersed people. Next, the author briefly describes the layout of the wall, mentioning five open gates and two closed ones. Strikingly, in the design of the Haggadah of Venice there are also two walled gates (Fig. 8).

Figure 8: The two walled gates of Jerusalem: Passover Haggadah, Venice (1624). Photo courtesy of Ets Haim – Livraria Montezinos (Amsterdam), all rights reserved.

According to David Senior, both gates bear the name of “gates of piety”. Perhaps in this mention we find a clue to the hope that propelled a daughter of the Hebrew nation in 1665 as she laid down her last will in her house in the Ghetto Vecchio, recommending that a lighted lamp be dedicated to her in the city of Jerusalem and putting her trust in the “name of Adonay, Lord of Hosts, in whom I firmly believe”.

Bibliography:

Imanuel Aboab, Nomologia o Discvrsos legales. Compuestos por el uirtuoſo Haham Rabì Imanuel Aboab de buena memoria, Eſtampados à coſta, y despeza de ſus herederos, en el año de la creacion 5389 (Amsterdam, 5389/1629).

Rafael Arnold, “Aus eins mach drei. Die Pessach-Haggada (Venedig, 1609) in Ladino, Italienisch und Jiddisch”, in Der übersetzte Gott, ed. Melanie Lange and Martin Rösel (Leipzig: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, 2015), 108–32.

Pamela Berger, The Crescent on the Temple. The Dome of the Rock as Image of the Ancient Jewish Sanctuary (Leiden: Brill, 2012).

Ignacio Chuecas Saldías, “Testamentos de judaizantes hispano-portugueses (1587-1673)”, Revista de Fontes 8 (2018): 7–32.

Israël Salvator Révah, “La relation généalogique d’I. de M. Aboab”, Boletim Internacional de Bibliografía Luso-Brasileira 2 (1961): 276–310.

Acknowledgements:

I would especially like to thank Heide Warncke, curator of the Ets Haim Library (Amsterdam) for her generous and positive response to my request to use the images of the edition of the Haggadah of Venice (1629) kept in her institution.

Biography:

Ignacio Chuecas Saldías is full professor in the Faculty of Humanities and Communications, member of the CIDOC research centre and director of the interdisciplinary doctorate programme in the Humanities at Finis Terrae University in Santiago, Chile. He is specialized in the Portuguese diaspora and especially in New Christian, converso and Judaizing identities. His works touch on aspects of social history (family networks and agencies) and material culture (circulation of knowledge and objects among the New Christian diaspora). He is currently principal researcher for the Fondecyt Initiation Project No. 11200876 “Portuguese between the Reynos del Pirú and the Great Kingdom of China (16th–17th Centuries)” and the “Praying to the God of Israel according to the Portuguese Tradition (16th–18th centuries)”, project sponsored by the “Alberto Benveniste” Centre of Sephardic Studies, Faculty of Arts, University of Lisbon, Portugal.