There is no denying that the invention of paper was a major human accomplishment and a medium that had a profound impact on society. It turned the dissemination of information and record keeping into much easier tasks and thus had a great impact on human existence. Researchers often consult archival material for the written or drawn content to find answers for their research questions, but more often than not, paper as a material is disregarded. Paper itself, however, is a treasure trove of clues left behind by the mill manufacturer waiting to be investigated. Just like a burglar unintentionally leaves fingerprints behind, the mill manufacturer leaves behind watermarks, chain and laid lines produced by the moldmate. The thickness of the paper, appearance and material composition are also features that vary from one mill to another. While a watermark was incorporated intentionally to identify the manufacturer or the grade of paper, the other features were simply a result of the paper making process. Fortunately, advances in Artificial Intelligence technologies can aid in facilitating the “detective” work and identify the provenance of paper in terms of manufacturer and date using these discriminatory features.

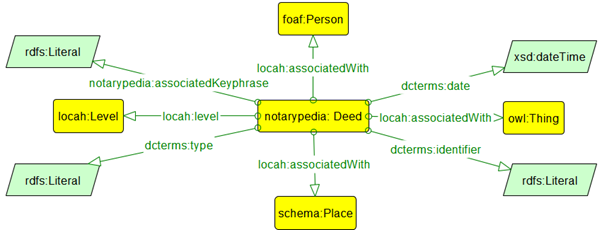

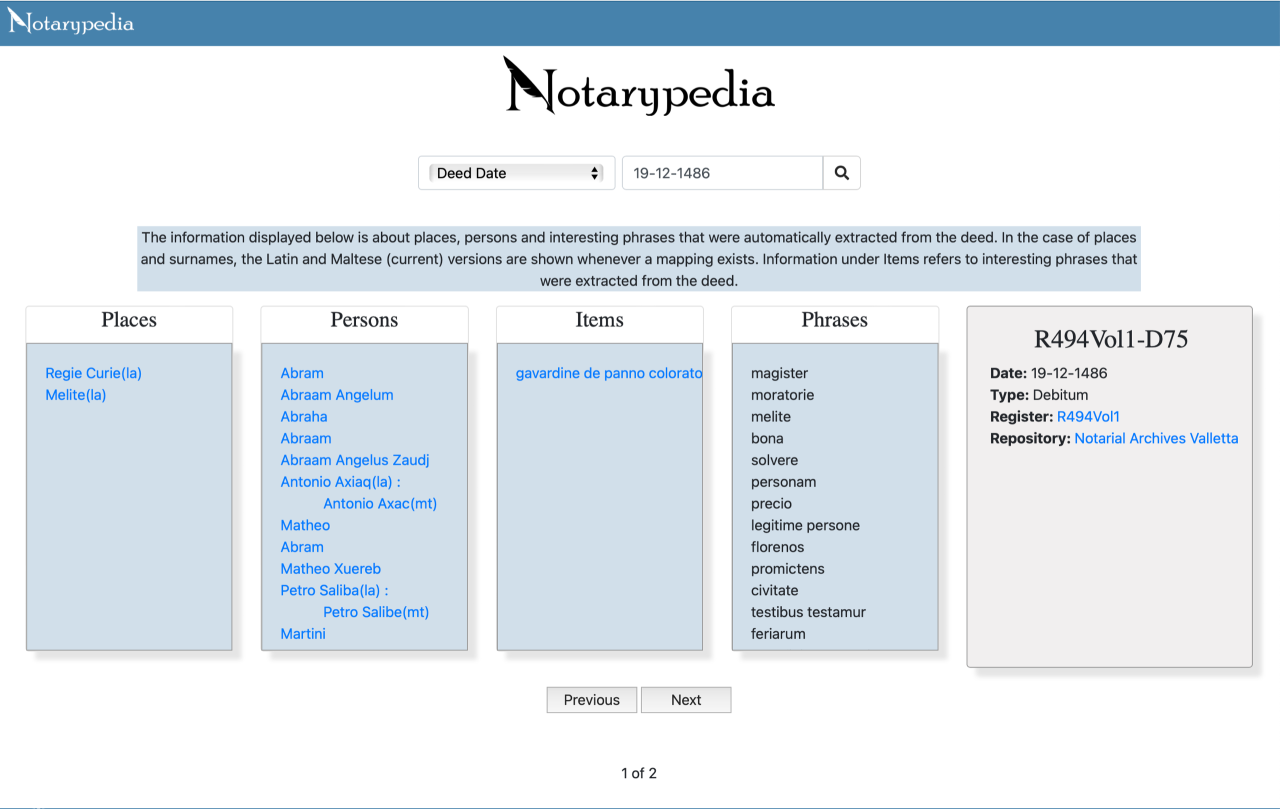

My research so far focused on the contents of historical notarial registers found at the Notarial Archives in Valletta, Malta. “Notarypedia: Knowledge Graph representation and Visualisation of Cultural Heritage Texts” [1] proposes a solution that extracts entities and relationships from the contents of medieval Latin manuscripts and represents them as a Knowledge Graph. Techniques such as Named Entity Recognition (NER), automatic keyphrase extraction and text classification were used to automatically extract entities including dates, people, places, deed types and keyphrases. Relationships between these entities including genealogical and geographical relationships were extracted and represented in the Notarypedia Knowledge Graph as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Notarial Ontology

An ontology including vocabulary to represent these entities and relationships was defined and enabled the user to traverse the data in a more intuitive way imitating the serendipitous thinking of humans, thus facilitating semantic search as shown in the prototype user interface shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Notarypedia Prototype

This methodology of representing manuscript metadata is scalable and highly flexible, thus enabling the representation of different metadata from different domains. So why not expand the initial idea of representing the contents of the manuscript, and also represent the manufacture of the paper in the manuscript? It is time to start looking at a manuscript as a material artefact with interdisciplinary data stored in a single storage hub where knowledge completion techniques can aid in aggregating data from different domains and sources using computational power and Artificial Intelligence techniques.

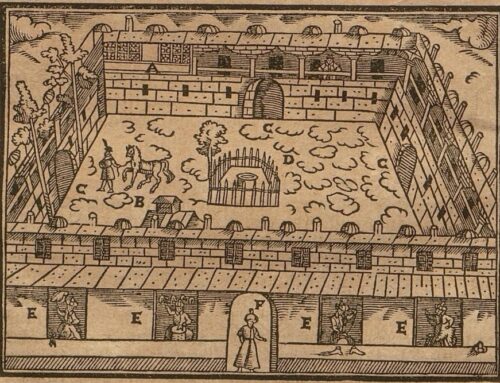

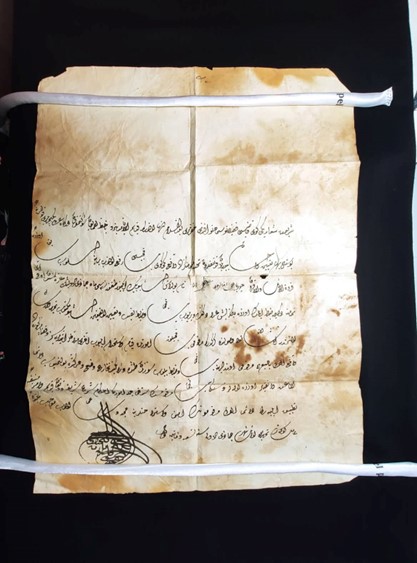

The Notarial Archives collection located in Valletta, Malta is of particular interest as it is an uninterrupted collection from the 15th century to the present day. Paper was most probably imported from other neighbouring countries. This can shed light on the trends of different paper used along the years and how paper technology developed over the years. Corsairing activities resulted in a small collection of seized Ottoman Turkish letters, as shown in Figure 3. The paper used in these letters may provide a comparative study of Islamic paper and European paper. This small dataset is part of research conducted by the conservator Chanelle Briffa who is recording a variety of paper features including discolouration patterns, visual qualities such as distribution of fibres, inclusions and translucency, paper characteristics including thickness, colour and burnish and mould construction with relevance to chain line characteristics and laid line characteristics. All these “new” recorded features may be important discriminatory features that aid in improving the accuracy of paper identification.

Figure 3 Ottoman Turkish Letter (Notarial Archives, Valletta)

Figure 3 Ottoman Turkish Letter (Notarial Archives, Valletta)

X Shen et al. [2] already experimented with watermark recognition, publishing a dataset of watermarks from the Briquet catalogue. This is a starting point, where they achieved a 55% Top 1 Accuracy in their Top 5 matches predictions. They experimented with one-shot recognition, cross domain recognition and local features recognition. As previously discussed, the watermark is not the only discriminatory feature that distinguishes a manufacturer from another. This was recognised by Gorske et al. [3] whose research focused on moldmate identification in pre 19th-century European paper. They considered structural features of handmade laid paper including the watermark shape and placement, the chain line intervals and laid line density.

Although there are great achievements in AI modelling, this research area still presents several challenges. Large scale, curated, fine-grained public databases are scarce. Watermarks are difficult to visualise and record, as they are quite faint and often obscured by the presence of text or images on the paper. Traditionally, conservators hand-traced watermarks from old papers onto clear paper to record them. The Rijksmuseum’s Conservation and Science division is experimenting with electron radiography, thermography, low energy X-rays, and transmitted backlit photography. The UK National Archives [4] is investigating the materiality of historical documents in their collection using a new multispectral imaging (MSI) system, which involves illuminating the documents with a variety of LED lights (ultraviolet, visible, or infrared radiation) and using a very high resolution camera (150 megapixel) to capture the transmitted light, reflected light, or generated luminescence. In a time when the term “digitization” is the new buzz word in the archival domain, one should consider what data should be captured about each manuscript. Should documents simply be scanned to have an online copy where researchers can flip through the contents or should we start going the extra mile and represent every detail of the manuscript using these available technologies? It is indeed a tedious and time-consuming task, but is it worth the effort in case some kind of natural or man-made disaster occurs?

Of course, watermarks and chain and laid lines features can have only small variances which may be due to the continual use of the mold or the creation of a new mold with the same watermark. Wire patterns become gradually deformed. Tolerance values should be included by using the statistical standard deviation to measure the dispersion of the data. Data augmentation may be used to compensate for strong lighting effects, paper stains and tears. As expected, blank papers make the perfect candidates for dating and provenance identification, but this is not always the case. Heavily inked surfaces tend to occlude some of the features I have just mentioned and render them difficult to identify in photos. Metrics based on the use of a ruler are important in such photos in order to facilitate the extraction of ratios. The number of pixels is not a good metric as these vary from one resolution to another. The distance from which the photos are taken is also a contributing factor to scale issues. The way that paper is folded including bifolios, quartos and octavos along with paper cropping for different uses may result in fragmented watermarks and incomplete chain and laid lines.

Research efforts to overcome these challenges may result in higher accuracies. This is a highly interesting area of research which would be of great profit to archival hubs all around the world. Merging the results of paper identification with the content of the manuscript in a Knowledge Graph, will enable the possible use of Knowledge completion techniques such as inference models and link prediction. The current ontology can be extended to include vocabulary to record the features of each folio. By describing the structure of the knowledge in a domain, the ontology sets the stage for the knowledge graph to capture the data in it. Unlike taxonomies or relational database schemas ontologies express relationships and enable users to link multiple concepts to other concepts in a variety of ways.

Bibliography

| [1] | C. Ellul, C. Abela and J. Azzopardi, “Notarypedia: A knowledge graph of historical Notarial manuscripts,” in On the Move to Meaningful Internet Systems: OTM 2019 Conferences, 2019. |

| [2] | X. Shen. et. al, Large-Scale Historical Watermark Recognition: dataset and a new consistency-based approach, Milan: 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), 2020. |

| [3] | S. Gorkse. et. al, “Moldmate identification in pre-19th-century European paper using quantitative analysis of watermarks, chain line intervals, and laid line density,” International Journal for Digital Art History, no. 5, pp. 6.14-6.32, 2020. |

| [4] | P. L. Pardo, “Watermarks: New ways to see and search them,” 30 July 2020. [Online]. Available: https://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/watermarks-new-ways-to-see-and-search-them/. [Accessed 16 September 2022]. |