Preparing for the Immigration of New Subjects: A Sketched Map of the Zadar Hinterland (Early Seventeenth Century)

During the sixteenth century, Venetian Dalmatia had to deal with large waves of immigrants arriving from the Ottoman provinces of the inner Balkan peninsula. Searching for a more secure and stable place to live, individuals of different origins (Bosnian, Greeks, Vlachs, etc.) abandoned their homes, goods and routines and chose to move to territories administrated by the functionaries of the Venetian republic. Driven away by fear of the Turks, losses caused by wars or incursions for plunder, or hopes for a new life in better circumstances, large groups of people, identified by different ethnic labels and the status of ‘Ottoman subjects’ (sudditi Turchi), encountered the Venetian authorities and its administrative customs in Dalmatia.

During the sixteenth century, the hinterland administrated by Venice on the eastern coast of the Adriatic proved to be insufficient to host and accommodate the increasing numbers of newly arrived inhabitants. Sixteenth-century Venetian Dalmatia consisted of the major coastal cities of Zadar, Šibenik, Trogir and Split and their rural hinterland, whose extension varied according to the shifting borders, war conquests or uncertainties regarding the rightful owner/ruler of the villages. Given the permanent threat of Ottoman incursions and scarce resources for subsistence, Venice was determined to take some measures in order to relocate the immigrants in other provinces of the Stato da Mar. Most commonly, the individuals who arrived in Dalmatia were transferred to Istria, which, in its turn, was affected by depopulation caused by drought and war. The new settlers were attracted by the offer of lands and rights to build houses, as well as the chance to maintain their organisation and develop their traditional activities. They were granted exemptions from tax payments for a specific period of time (usually five years with the possibility of an extension) and from service as rowers on the Venetian galleys. In addition, they received seeds to start cultivating the lands and some sort of state protection. On their part, these new Venetian subjects had to learn and respect the rules of the specific administrative jurisdiction where they settled, to collaborate with the authorities (captains, counts, podesta, etc.; also, to name a few men to provide military services when/if required) and to sell their crops or products in specific places while respecting the customary rules. Obviously, the interactions and accommodation did not always go smoothly and countless letters sent to the Venetian Senate mention complaints from both the new settlers and the inhabitants forced to interact with them.

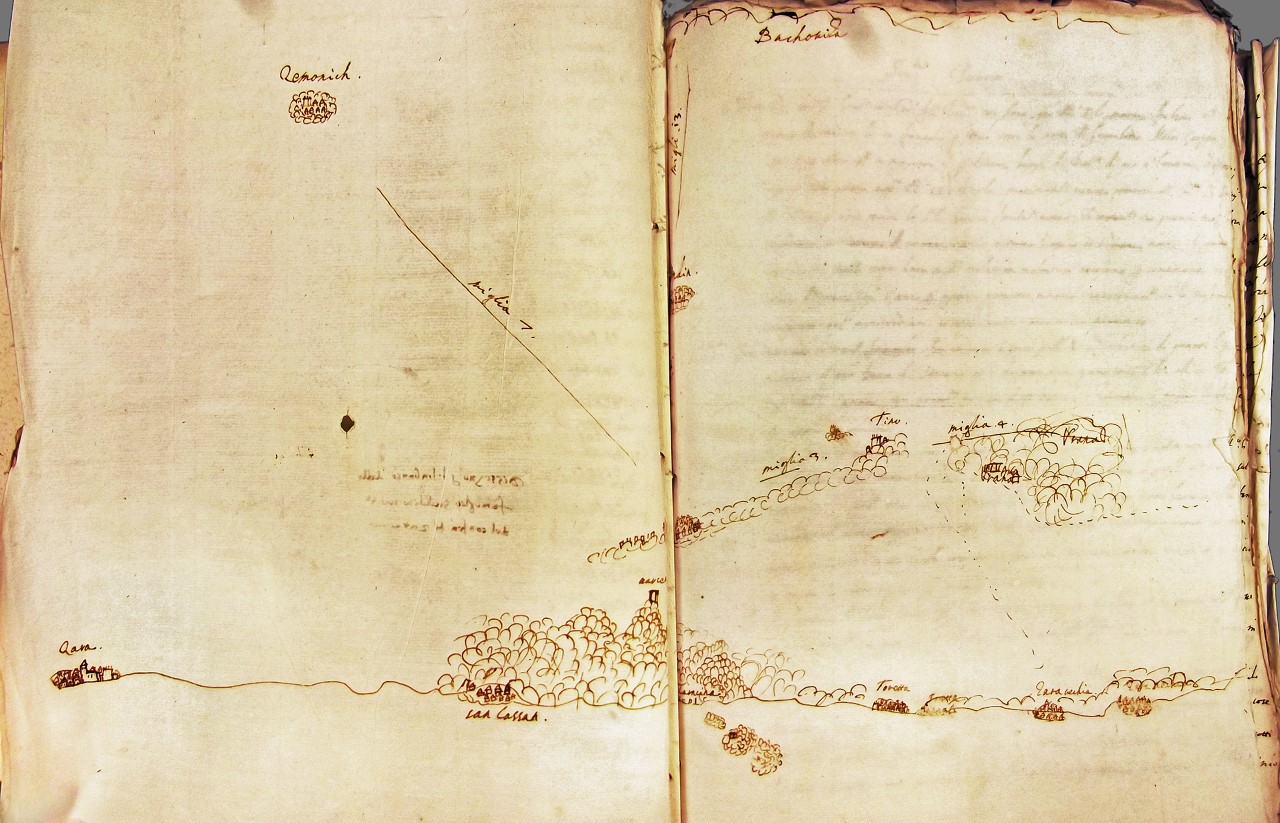

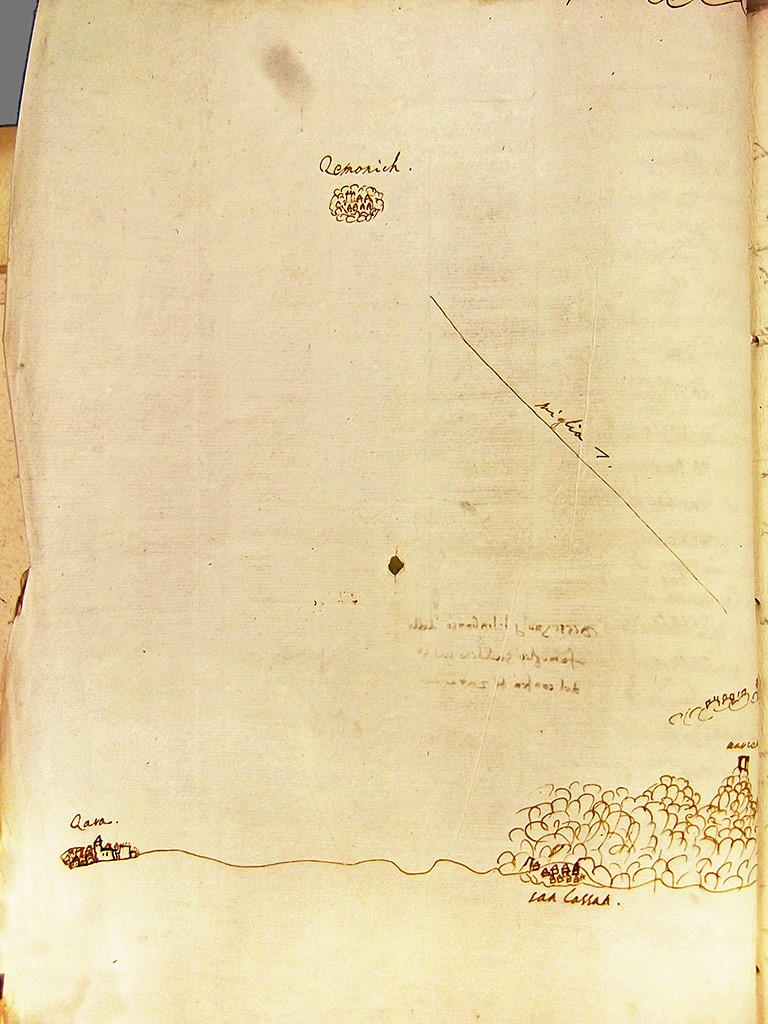

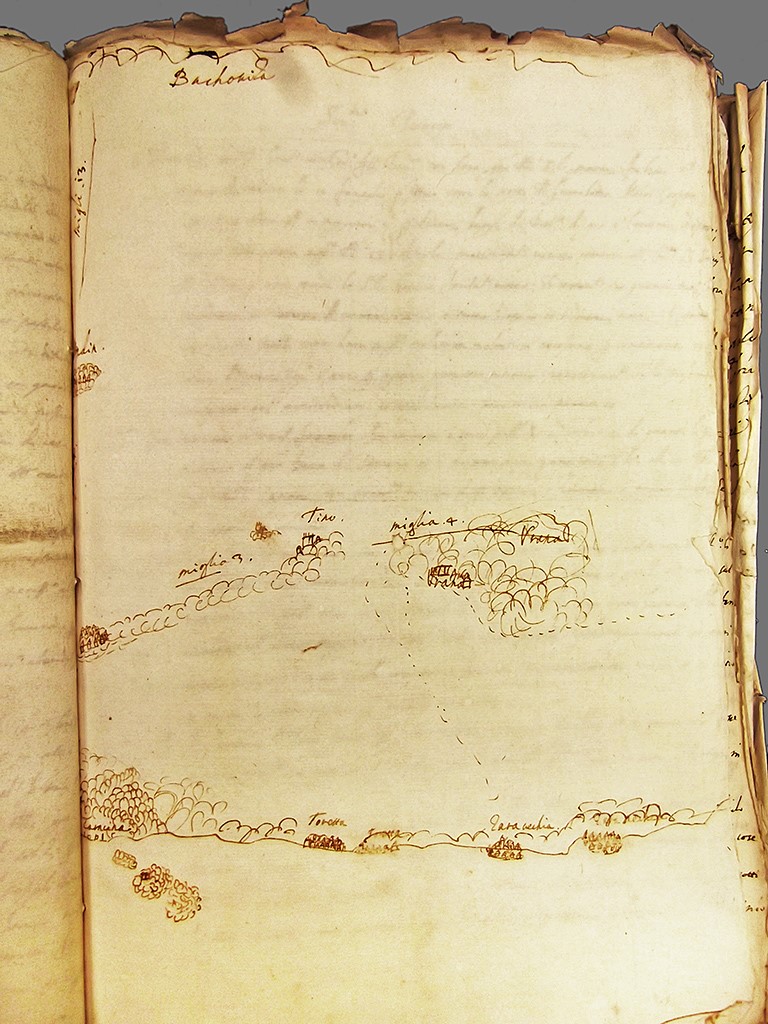

The sketched map presented here can be found on the back pages of a letter sent from Zadar to Venice concerning the organisation of such a transfer of settlers. The document was written on 23 April 1604 by the secretary Bartolomeo Comio in the name of two Vendramin brothers, Giacomo and Federico, who wanted to transfer 50 Christian families to Istria to settle them on their lands. In order to fulfil this transfer, they collaborated with the leader of the group to be moved, Milos Zuppanovich. In this case, the Vendramin brothers acted as intermediaries of the state and direct beneficiaries of the population transfer, with the purpose of populating and cultivating their lands in the hinterland of Rovigno. One of the issues they mention in their letter is the new settlers’ inability to adapt to the living conditions and climate of Istria and therefore these new settlers asked to be transferred from Istria to Puglia, another traditional destination for immigrants arriving from Ottoman territories. Furthermore, their letter emphasises immigration to Puglia as one of the challenges they encountered in the struggle for the well-being of the maritime provinces of the Venetian Stato da Mar. (Fig. 1 and 2)

Figure 1 and Figure 2: Dissegnio et l’imbarco delle fameglie suddite turchesche del contea di Zara, file 10: Dissegnio et l’imbarco delle fameglie suddite turchesche del contea di Zara, Archivio di Stato di Venezia, reproduced by kind permission of the Archivio di Stato di Venezia, © Archivio di Stato di Venezia

Another aspect of interest resulting from this document are the steps detailed in order to obtain the permission from the state to transfer the families to Istria. They expressed their intention to travel to Dalmatia to discuss their plans with men who knew about families from the Ottoman territories willing to move to Istria and with the leaders of the families who were interested. The Vendramins mention previous transfer attempts of which they were aware: in 1600 four men (not named) facilitated the transfer of the Vratković Morlachs to the hinterland of Siena, or the case from 1602 of discussions with Chisanochi and Matteo Jugovich from Herzegovina, leaders of 60 families, to obtain their transfer and settlement in the rural hinterland of the island of Brazza. The group mentioned in our document was gathered by the harambaša Miloš Zuppanović, man of value and connoisseur of Ottoman military practices. Zuppanović prepared the people to be transferred to Istria by gathering all those interested from the villages of Goriza and Grastiani in Banadego (province of Croatia situated north-east of Dalmatia), and with the help of the general governor of Dalmatia transferred them to the hinterland of Zadar to wait for state approval and support for their settlement in Istria. A group of 300 individuals, of whom 80 men good to become soldiers, 3,000 small animals, 100 horses and 300 large animals were all waiting to cross into Istria. Assuring the senate of the full dedication of these new subjects, whose leaders had taken an oath on their bayonet, the Vendramin brothers asked for the central authorities to mediate with the local authorities from Istria (especially with the captain of Raspo, along with the police in charge of the villages occupied by the new settlers) which were not always keen to close their eyes to the accommodation difficulties that the new settlers might experience. They also expected to be helped with the expenses for the transfer and the gifts needed to prepare for it.

This short resumé of a four- to five-month transaction is but a glimpse at the organised transfer of people across the territories of the Venetian Stato da Mar. Throughout the sixteenth century, countless Ottoman subjects left their nido antiquo and became subjects of Venice. Some of them (Morlachs, Greeks, Albanians, Bosnians, etc.) later returned to Ottoman Banadego or Bosnia, some of them returned to Dalmatia (e.g., morlacchi Istriani settled in the hinterland of Zadar), others left Istria for the Italian states, but most of them remained in Istria and gradually became part of the province. What is to be considered even more from this briefly outlined case study is the fact that different individuals – Venetian citizens – were actively involved in organising the transfer of people, out of personal interest, but in respect of the rules and collaboration with the state. They became active agents in transimperial shared spaces (in our case, Dalmatia) and were careful to reach their goal without starting a diplomatic conflict. Attentive preparations, necessary waiting periods and useful local networks were put together to find solutions to the lack of resources. Even the sketchy drawing of the map provides us with an insight into the men who carefully calculated the distances between the villages where the people to be transferred to Istria were located, while waiting for the move to happen.

The role of the drawings presented here is to provide a pictorial statement of an individual initiative to obtain the approval and the support of the state administration. It puts together personal experiences, personal knowledge of spaces and people, and a mathematical approach to a deal with benefits for personal and general prosperity. In an era in which the art of political and military maps was quite advanced, and more and more experts dedicated their lives to creating more explicit and detailed representations of spaces and people, the sketched map drawn for the Vendramin brothers in 1604 puts the researcher in front of a more personal experience. Together with the document, the map emphasises once more the awareness and mobility of subjects who were not necessarily the most prominent state figures, and the significance of human networks and interactions.

*** More details about the case of the immigrants transferred by the Vendramin brothers can be found in Lia de Luca, Venezia e le immigrazioni in Istria nel Cinque e Seicento, PhD thesis, 2011, 147–49. However, the document presented here is new, so it adds to the information contained in the thesis.

Dana Caciur is researcher at the “Nicolae Iorga” Institute of History, Bucharest, Romania.