The sea is an anarchic passage; it evades any borders, it cancels out any trace of appropriation, it contests the arché of order and subverts the nómos on land. For this reason, the sea also preserves the memory of another clandestinity, that of oppositions, resistances, struggles. Not the clandestinity of a stigma, but rather that of a decision (Di Cesare 2020, 125).

Perhaps this affirmation by the Italian philosopher Donatella Di Cesare is too neat. We know that even the waters of the oceans, seas and their depths are being appropriated and increasingly resourced. Nevertheless, it serves to mark a certain limit in our reasoning and political calculus. At sea something always exceeds and flees the semantics secured on land, in the territories, buildings, monuments and laws. Thinking of the Mediterranean, Fernand Braudel (1995) famously proposed considerations of the deep rhythms of time, more recently Peregrine Horden and Nicholas Purcell (2000) have encouraged us to confront the corruptive complications of multiple ecologies. The Mediterranean does not settle easily in predestined critical or cultural location. In immediate terms, contemporary European politics and legislation, concentrated in the figure of the ‘illegal’ migrant, inadvertently expose deeper archives; these invite us to revaluate this body of water and associated histories. Sea water is striated. It follows neither a single history nor a unique map. It is worked up and worked over not only by social, but also by physical, animal and chemical, processes. To insist on these overlapping configurations is to register what exceeds and enriches the picture. Unregistered histories invest, cross and construct unsuspected maritime archives.

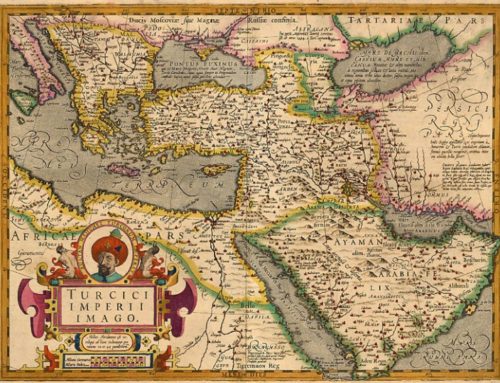

Further, to consider who gets to map, frame and configure the world, that is to understand geography as power, is also to ask who has the right to narrate. For the spatial organisation of knowledge is also a temporal device that logs, writes up and chronicles the political, cultural and philosophical administration of time. Commencing from the epistemological challenge of the sea, and abandoning national narratives and the prison houses of identity secured in the presumed stability of land-based institutions, we also discover that the objectivity of our intellectual anchors often fails to hold. As Merje Kuus has written: “Although nationalism and the nation-state are omnipresent categories of practice in our world, they are not necessarily the appropriate categories of analyzing that world”(Kuus 2017, 263). So, rather than simply adding the ocean and the marine world to existing understandings of political geography – from area studies and international relations to the renewed insistence of borders and the ubiquity of capitalist extraction through national and trans-national agencies – it might be instructive to look landwards from the sea precisely in order to bring fresh questions to the logic and languages of those categories and practices.

The sea is not merely a dialectical negation of the ground beneath our feet. It is something more than that; it breaks away from simply being an aquatic emptiness contrasted to the fullness of the land. Although claimed, administered and resourced by all the powers and technologies of modernity – from trade and tourism to energy supplies and pharmacological research (Steinberg 2001, 9) – we can choose to insist that the sea promotes an irreducible alterity. Beyond the heterotopic challenge of the slave, pirate and whaling ship, all charting modernity otherwise from the vessels of the maritime world (Gilroy 1993; Linebaugh and Rediker 2002; Casarino 2002), the challenge of the sea insists in its indifference to the powers ravaging its reaches and resources. It poses questions that cannot be readily captured in the representative logic that guides our rationalism. To echo Gilles Deleuze on the cinema, a theory of the sea is not ‘about’ the sea, but about the concepts that the sea gives rise to (Deleuze 1989, 280). At this point a maritime ontology, in this particular case tied to the Mediterranean, proposes the laboratory of another modernity.

Going off-shore for a moment allows us to renegotiate our premises while being at sea (a term which also implies being lost). When we no longer think of the Mediterranean and, in particular the centrality of the in-between status of its marine ambient – the Medi-terranean – as the object of our geographical, historical, sociological and anthropological gaze, then a certain knowledge formation comes unstuck and begins to drift. Of course, the Mediterranean is itself an invention, object of a regime of knowledge produced by historical and political forces that since 1800 have bound it into the particular political economy that today dominates the globe (Chambers 2008). Yet from its African and Asian shorelines the Mediterranean has rarely been constructed and conceived in the fashion we are presently accustomed to. Let us simply consider that the most widely spoken language in the Mediterranean basin, in all its dialects and variations, is Arabic. Perhaps an ‘Arabic Mediterranean’, in the manner we Europeans are accustomed to consider it, does not exist. In fact, the term al-Muttawassit only begins to circulate in Arabic at the beginning of the Twentieth century (Matar 2019). Europe has imposed a unity on what elsewhere carried multiple names. This distinction and fracture draws attention to a more open archive: one whose languages are not merely of European provenance. It suggests other perspectives and lexicons that do not automatically mirror or mimic a subaltern and repressed version of what we on the northern shore have elaborated. Rather than propose a sharply separate and unregistered alternative, we need to consider the underside and unconscious dimensions of a Mediterranean which, when laid out flat as the map, betrays all the limits of its modern European inscription.

Other histories and cultures have traversed its waters. They have proposed temporalities that are irreducible to the crushing linearity imposed by Occidental ‘progress’. I have in mind the Fourteenth century journeys of Ibn Battuta from West Africa and the Atlantic coast to central Asia and China, or the temporal spirals of historical sociology elaborated by his slightly later contemporary Ibn Khaldūn. In the present order of knowledge these examples, if considered at all, are ‘minor’ proposals, exotic curiosities set in the margins of the modern academic machine and its self-assured epistemic order. What I am proposing here, following Walter Benjamin’s noted theses on the philosophy of history, is to shift the historiographical axis 180°. Adopting a view located not in a temporal lag, but from a contemporary below, interrupts the chronological axis. Rather than being secured in a linear narrative, we find ourselves in a constellation where the past does not simply pass but rather accumulates in the present as a set of interrogations and potential interruptions (Benjamin 2015).

Carlo Rovelli suggests that science is about a continual process of proposing possible views of the world through informed rebellion (Rovelli 2016). For Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari philosophy is fundamentally about the invention of concepts (Deleuze and Guattari 1994). Applying such perspectives, while avoiding the purported ‘cutting edge’ of neoliberalism always looking to capitalise on novelty, involves embarking on a radical trans-disciplinary approach to our habitual coordinates. This is to consider the structure of time not in terms of a flow in which events occur, but rather of understanding and experiencing time as it emerges from events. The latter can accelerate, slow and deviate the steady pulse of chronology. This intersects with the Gramscian invitation to consider time and space always in political, never in neutral, terms (Chambers 2015). It means, and now moving into our argument, to propose understandings of the Mediterranean that are always subject to contestation and reconfiguration; that is, to historical processes and shifting geographies of power.

Beneath the surface, beyond the purview of the intellectual panopticon that believes all can be rendered transparent to its will, we can consider the Mediterranean from what is sustained and suspended in its waters. This suggests the strategical move of beginning to think with the sea; no longer as a mute object or dumb accessory, but as an active participant in the political coordination of the world; no longer merely a physical space to be crossed and controlled, but a historical participant that permitted modern sea-borne empires and the Occidental fashioning of the planet (Steinberg 2001). What today rises to the surface and floats on its waters – dead mammals (both human and non), together with other disappearing life forms – brusquely and brutally returns the unregistered archives of a migrating modernity and its ecological breakdown to the present. The human migrant, denied passage over its waters by an Occidental legal apparatus that unilaterally appropriates the right to universal law while frequently denying the immediate ‘law of the sea’ to save and rescue, provides a central key with which to reopen and rerun the accredited narrative of Western modernity. The lives involved are apparently voiceless, reduced to objects in the brutal inflation of political discourse where the spectre of alien ‘invasions’ and the denial of climate catastrophe are deeply entwined in the maintenance of the status quo and white hegemony. Yet these bodies do speak. Whether alive or dead their presence interrogates the smug assurance of an official modernity that assures us all is under control, that further progress will find a solution for the wretched of the planet, for the wretched planet (Fanon 2004; Gray and Sheikh 2018). Pulled into an ‘ecological’ vision – one not simply restricted to ‘nature’ and its accompanying sciences – we enter darker spaces than their accommodation of counter-histories.

Restricting ourselves to the human dimension, but the ecology of life and survival clearly precedes, exceeds and sustains the category, other histories emerge from the depths of modernity. Human migration is transferred from a peripheral question, confined to the social and economic margins, to joining the mainstream of the violent and enforced mobility of goods and capital in the making of the present-day world. Migration now becomes the history of modernity. The global and mobile exploitation of human labour, together with the world-wide raiding of material resources, that fuels capital accumulation and material development, not only persists, but insists. What was distanced, even hidden, far away in the colonial spaces of the plantations and the mines, the slave trade and subsequently in the politically refused slums of the industrial and post-industrial world, explicitly returns to triangulate our modernity with the constitutive coordinates of capitalism and colonialism and their moral endorsement in racialized distinctions. If this means to paint the picture with very broad brush strokes and register that the colonisation of the planet means that all Europeans are ultimately white settlers, it nevertheless allows us to begin to assemble the flotsam of the present into a certain critical coherence. This cuts into the apparently seamless sovereignty of the West on the world to retrieve other histories, and consider other horizons. Here the modern market economy and its dependence on subordinate labour, most dramatically rendered explicit in modern slavery and indentured labour – from Eighteenth century plantations in the Americas, to tomato pickers in southern Italy today – intersects the deeper tempos of ecological decomposition and re-composition that draw together time scales that are both human and beyond.

Much of the thinking expressed here matured in the company of a FLOATS (Floating Laboratory and Action at Sea) seminar near Samos in 2019, sailing between Greece and Turkey, Europe and Asia, on the Archipelagos Institute of Marine Conservation vessel Aegean Explorer.[1] Thinking on water, travelling by sea, further encourages the interruption of the claims of a single political and intellectual sovereignty over the world. On a horizontal plane, the historical, political and cultural construction of the Mediterranean is largely restricted to the spacetime paradigm of European provenance that pretends universality. Present day political and legal barriers against migrants crossing the sea, amounting to an undeclared war on the water (Chambers 2019), are the most potent signs of the limits of this purported universalism and its associated humanism. Meanwhile, dropping down the vertical axis brings into play the complex stratification of human and non-human life in the aquatic domain. This poses fundamental questions about the existing disciplinary divisions of knowledge and promotes an overspill between the social and natural sciences in an altogether more extensive ecological frame. The ready identification of ‘objects’ of scientific study and the positivism of their methods breaks up; the abstract endorsement of a-priori procedures and a single time frame is intercepted by the rigour of following a multiplication of material scales and processes. Against the progressive logic of fine-tuning and improving the existing knowledge apparatus to incorporate these critical proposals there now emerges a deeper set of epistemological questions: these challenge the present political economy of knowledge. Like the sea these questions can never be fully absorbed nor tamed, for they request a profound undoing and redoing – not a cancellation – of an intellectual arrangement that is also a historical and political settlement (Hallaq 2018).

So, if geography cannot be spliced apart from history then geopolitics and area studies, but also the sociology, historiography and anthropology, of the Mediterranean – all disciplines forged in the making of modern Europe and the West – can no longer pretend to hold their previous status as disinterested and neutral forms of knowledge. Their limits lie not in the failure to extend and further refine their appropriation, but rather in continuing to insist on extending sovereignty over the world thereby continuing the violence of the colonisation of the planet. Cancelling respect for alterity and refusing to engage with difference, is to exercise an exclusive knowledge over others and promote a divine reach untrammelled by the complexities and restrictions of the planetary habitat. At the end of the day, like all colonialisms (Memmi 2016), it amounts to intellectual fascism. Further, and perhaps even harder to accommodate, History, as a discipline seeking to collate, document and render the passage of the world legible, is itself fundamentally a colonial apparatus of power (Satia 2020). A purported objectivity that guarantees its universal and scientific claims slips into its own particularly history embedded in Occidental philosophy and its episteme. This, too, is the ‘coloniality of power’ (Quijano, Ascione, Seth).

Is Occidental knowledge intrinsically part and parcel of the historical processes that led to establishing the West as the universal measure of mankind? Is it possible to separate modern social and human sciences from the precise geo-historical matrix that formed, financed and institutionally established their legitimacy and authorised their knowledge? Just as they can be a history of the discipline and practices that have produced ‘history’, so, too, there can exist an anthropology of anthropology, a sociology of sociology. All of which is to reference a political geography of knowledge formations. Such self-reflection hardly begins to scratch the surface of the modern power-knowledge apparatus, its languages, premises and protocols. A deeper historical cut cannot avoid the intricate binding of our knowledge formation to the violent fashioning and colonisation of the world. The modern university, and the division of intellectual activities into fields of competence precisely gain in certitude as they lose sight of the brutal historical processes that sustain them. Rendering the world manageable by dissecting it in disciplinary competences is precisely to control, define, catalogue and control. Research and academic practices consistently expose the colonial constitution of Occident modernity in their assumptions and languages. If the physical extension and metaphysical justification for the appropriation of the planet continue to coordinate and frame the languages of knowing and understanding then any appeal to scientific ‘neutrality’ and purported objectivity can only be met with historical and epistemological scepticism.

Returning to the shorelines of this essay, in the intricate meshing of the Mediterranean and modernity today we persistently encounter Occidental violence and racism. It is intrinsic to the structure and exercise of power. Taught to consider such factors at a distance, confined to the past and extra-European spaces, what is occurring right now in the Mediterranean – from migration, mounting deaths at sea, dictatorships, uprisings and revolt on its African and Asian shores – returns that colonial past to the present. Further, it also reminds us that both modern colonialism and racial hierarchies initially emerged here. A century ago mass migration across the Mediterranean involved only Europeans as they journeyed to colonise Algeria, Libya, Tunisia and Palestine. The structural engagement and political appropriation of North Africa and the Middles East has in the modern era always been accompanied by race as ‘its ordering principle’ (Robinson 2000, xxx). For: “It was there—not Africa—that the ‘Negro’ was first manufactured.” (Robinson 2000, xiii). Alongside the contemporary situation in which black people everywhere in the ‘civilised world’ find themselves, one has only to register the continuing stereotypical subordination of the modern ‘Arab’ and ‘Muslim’ to capture the sense of these observations. Although studiously avoided, ironed away in the creaseless maps of political affairs and area studies, lost in the inevitable ‘progress’ of European histories and the bland benevolence of their cultural lexicons, the epistemological binding together of capitalism, colonialism and racism coordinating the making of Occidental modernity is recursive. European colonial violence, both from back there in Africa and the Americas, and last night on the waters of the Mediterranean, has produced a continuum of racial terror whose structure of power is persistently ghosted by those seeking social recognition and historical justice.

Today in the Mediterranean, Libyan patrol boats and concentration camps, financed by the European Union, are trying to block historical movement. To insist that modernity is itself a migratory apparatus that continually traverses waters and seas – highlighted in European maritime empires, in the slave trade from Africa to the Americas, in mass migrations from the rural poverty of Nineteenth-century Europe, and today in movements from the south of the planet – is to challenge stable referents of understanding. In the border regions where the modern state and its democracy seeks to regulate, control and deter migratory flows we most acutely register the limits of our grip on the world. In these marginal spaces, in the borderlands, the levelling mechanisms operated by Western reason as the tools and syntax of global management find themselves in deeper waters. The hegemony of the modern European subject, rendering the world objective through cancelling the specificities of the lives that disturb his and her order of knowledge, is set adrift. Precisely such a manner of thinking, making the world fully knowable and transparent to a particular will to power, today explains the “disregard for the lives lost on the streets of the United States and the Mediterranean Sea” (da Silva 2017). The presence of the contemporary migrant – her life and death – not only challenges the juridical definitions of rights and citizenship, and fragments the national collocations of belonging and cultural identity; it also opens up the complex constitution of what historically, culturally and juridically makes the West the West. A hole opens in time, the past is rendered proximate to contemporary concerns through the repressed archives of the present. Receiving and assembling a historical inheritance in this manner leads to building an alternative sense of the present. It leads to slicing up the body of modernity to produce another critical montage. This allows us to engage with the intertwining of the represented and the repressed in an emerging critical constellation. Here we cannot avoid registering the global injustice sustained by laws that guarantee, in its abstract and universal indifference, the general equivalence of capital.

One of the sharpest forms this radical realignment takes today comes from Black critical thinking. Aimé Césaire’s and Frantz Fanon’s critique of European humanism, their insistence on a humanism “à la mesure du monde”, is now increasingly amplified in the ongoing disturbance and rearranging of Occidental archives. When in 1928, anticipating Frantz Fanon’s “Look! A Negro!” in Peau Noire, Masques Blancs (1952), the African American writer and anthropologist Zora Neal Hurston wrote “I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background”, she caught the essential: objectified, caught and captured in the dehumanising position of being black in white society (Hurston 1928). Such a critical vein acquires increasing force in the retrieval of the centrality of the Black Atlantic experience and its fundamental contribution to the economy, culture and political institutions of the West. More recently this has recently been carried over into fresh critical considerations that respond to the need “to conceptualise the politics of contemporary blackness” beyond “the reductive orthodoxies of institutional methodologies and sociological empiricism” (Brar and Shama 2020, 89). Beyond the historical passage from the 1980s to the 2000s, from Black British Cultural Studies to North American Black Critical Thought, this mobile assemblage – from Stuart Hall and Policing the Crisis (1978) to Christina Sharpe’s In the Wake (2016), to name just two key texts – points to the ongoing trans-Atlantic meshing of the diverse temporalities of being ‘black’ in the decaying imperial centres of the First World. It is also where the critical insistence of the black diaspora crosses the lives and deaths of today’s migrants in their mutual constitution of modernity through their shared negation by that very same modernity. Maritime archives oversee the collapse of simple chronologies and secure unsung connections, composing the contemporary constellation of the Black Atlantic and the Black Mediterranean.[2] This intellectual assemblage is destined for further configurations in and from the south of the planet announced, for example, in the work of the Cameroon philosopher Achille Mbembe and his insistence on the becoming black of the world (Mbembe 2017). Rather than a linear heritage, this is a constellation whose stars and planets provide different illuminations in diverse tempos and spaces: W.E.B. Du Bois and Zora Neale Hurston, James Baldwin and James Brown do not disappear, the bass of Jamaican reggae and dub is constantly present, and the repeating poetics of the Caribbean continues to echo. It is sedimented in what Paul Gilroy called the “slave sublime” of the blues in music, literature and the visual arts. Such a critical remapping has been accompanied and nurtured by the accelerating refusal to accept the “afterlife of slavery” (Hartman 2006) in the state authorised racism of the policing and surveillance of our broken democracies.

This suggests an epistemological shift: induced both from within a dismantled Occidental heritage and through an intrusion from the externalised and marginalised ‘outside’ (which given the planetary constitution of modernity is never outside). Among the results there has been the increasing intersection between archival work and postcolonial art; that is, between research in the disquieting and violent archives of Western modernity and art against the grain proposing the modernities of previously unauthorised subjects, histories and lives. As James Baldwin pointed out many decades ago, people who live beneath and below the power bloc, in the subaltern worlds of the marginalised, the negated and the forgotten of the multiple souths of the planet, know far more of the hegemonic world than that world knows about them (or of itself). In the asymmetrical relations of power that structure the histories of the present lies not only the registration of the powers of brutal appropriations but also the potential of a critical cut and epistemological interruption. In Peripeteia (2012), John Akomfrah’s reworking of Albrecht Dürer’s study of a black male and female figure at the beginning of the Sixteenth century, matter once considered out of place now pushes an established arrangement of knowing the world out of joint. Not only do we comprehend that the world is wider and far more than us, but we begin to hear and learn from what exceeds and refutes our authorisation. This means to crease the existing map and perforate it with other trajectories. It is where, and listening to non-white experience, fugitivity, lines of flight and exercises in opacity open up new understandings of critical and epistemological power.

I think that a radical practice is not directly accessible if one is not one of those naked humans, as Glissant spoke of the “naked migrant,” a figure of radicalism, an echo of the Maroon who must rebuild everything in the space of escape. At that precise moment, there is a form of contradictory power in destitution, a form of optimism in obligatory survival. It’s the fundamental optimism of the slave who has left the plantation, who walks without knowing where to go, carried by an enormous desire to live that will allow him to pass beyond death (Marbouef 2019).

The return of this archive within the repetition of the history of the Occidental art canon, seeds aesthetics with an ethics bound to the measure of the world. This is what constitutes the potency and poetry of what I consider postcolonial art. Further, and to augment a critical disavowal and to take ‘Art’ and ‘aesthetics’ in hand, we need to recognise them as recent inventions of European modernity. They betray a precise historical formation and cultural configuration. What we identify as art is a limited exercise in the languages of our epistemic order, and not a judgement of universal validity. Remaining within the Mediterranean, the very idea of ‘Islamic art’ (invariably considered ‘ornamental’ with respect to the great tradition of Occidental provenance) underscores the mis-match historically arising between diverse cultural formations that are irreducible to a single measure. What falls outside the frame of Occidental concepts and conceit nevertheless persists and insists. What we call art, can appear in another assemblage of sense and sensibility that draws us beyond the categorisations of what we consider modernity. In other words, and digging deeper, the secularisation of Christianity as another name for modernity and its presumptive redemption of the world, fails to receive or respond to the cultural force of Islam through refusing its alterity as a component within the modernity it thinks it owns. This exploration of the “epistemological assumptions of the secular”, its inscription in the capitalist infrastructure of the modern nation state as political hegemony, together with the largely unexamined dependence, and not distinct separation, of the sacred and the secular, has been consistently exposed by Talal Asad (2003), and more recently extended by Irfan Ahmad (2017). To consider these wider coordinates means to rethink ‘art’ and undo the aesthetics that binds it to one particular order.

Art history has developed its paradigms through the analysis of Western art that might be better termed Christianate, underscoring the modern transposition of premises informed by European Christianity as culture which permeate secular Western societies and which often serve as a measure for the assimilation of those designated as other. Generously globalizing these paradigms, it has recognized the art of other cultures to the extent that it suits this filter. When applied outside Europe, the term ‘art’ represents a form of epistemic violence through the renegotiation of objects from the intrinsic logic of their cultural–social life into an extrinsic realm of analysis and modern commodification in private collections and museums. It denigrates the cultures in which works were produced as intellectually mute and lesser than the narratively produced, imaginary collective designated as ‘our (Christianate) own’(Shaw 2019, 11).

Here cultural differences, and their inevitable ranking via figurations of race, critically intersect definitions of art and aesthetics. This is what David Lloyd most effectively captures in his book Under Representation: The Racial Regime of Aesthetics. He insists that aesthetics is not merely about art, but “rather has functioned as a regulative discourse of the human on which the modern conception of the political and racial order of modernity rests”; it arises out of the necessity “to substitute for the immediacy of political demands and practices an aesthetic formation of the disinterested and ‘liberal’ subject” (Lloyd 2018). In this far longer and deeper wave we encounter our proximity to a past we presumed has passed, consigned to a closed chapter in the history of modernity. On the contrary, time flows back and forth, and returns us to the precedents that established a particular order and its contemporary distribution of wealth, political power and cultural authority in the ongoing colonial constitution of the present. As the artist Cameron Rowland, once again centring slavery and the sea, succinctly puts it: “Abolition preserved the property established by slavery. This property is maintained in the market and the state” (Rowland 2020).[3]

These are some of the lessons I have learnt from the sea.

This article, published here in preview, will appear in print and open access with De Gruyter in December 2021in the miscellany edited by Angela Fabris, Albert Göschl and Steffen Schneider, in the series Alpe Adria and surroundings. Mediterranean itineraries. Border literature and cinema (directed by Angela Fabris and Ilvano Caliaro). See: degruyter.com/serial/AAIM-B/html

References

Ahmad, I. (2017). Religion as Critique: Islamic Critical Thinking from Mecca to the Marketplace. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Asad, T. (2003). Formations of the Secular. Christianity, Islam, Modernity. Stamford.Stanford University Press.

Benjamin, W. ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’. Illuminations. London: The Bodley Head, 2015

Braudel, F. (1995). The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Brar, D. S. and Sharma, A. (2019) ‘What is this ‘Black’ in Black Studies? From

Black British Cultural Studies to Black Critical Thought in UK arts and higher education’, New Formations, 99.

Casarino, C. (2002). Modernity at Sea. Melville, Marx, Conrad in Crisis. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Chambers, I. (2008). Mediterranean Crossings. The Politics of an Interrupted Modernity. Durham: Duke University Press.

Chambers, I. (2015). The Southern Question… again. Andrea Mammone, Ercole Giap Parini, Giuseppe A Veltri, eds. The Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Italy. London: Routledge.

Chambers, I (2019). War on the Water. Sink without trace. Exhibition catalogue. Available at : https://mediterranean-blues.blog/2019/08/08/sink-without-trace/ (Accessed 20 August 2019).

da Silva, D.F. (2007). ‘1 (life) ÷ 0 (blackness) = ∞ − ∞ or ∞ / ∞: On Matter Beyond the Equation of Value’, e-flux #79: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/79/94686/1-life-0-blackness-or-on-matter-beyond-the-equation-of-value/.

Deleuze, G. (1989). Cinema 2: The Time Image. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. (1994). What is Philosophy? London: Verso.

Fanon, F. (2004). The Wretched of the Earth. New York: Grove Press.

Gilroy, P. (1993). The Black Atlantic. Modernity and Double Consciousness. London: Verso.

Gray, R. & Sheikh, S. (2018). The Wretched Earth: Botanical Conflicts and Artistic Interventions’, Third Text. Vol. 32, 2-3. 163-175.

Hall, S., Critcher, C., Jefferson, T., Clarke, J., Roberts, B. (1978/2013), Policing the Crisis. Mugging, the State and Law and Order. London: Red Globe Press.

Hallaq, W.B. (2018). Restating Orientalism: A Critique of Modern Knowledge. New York: Columbia University Press.

Hartman, S. (2006). Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Horden, P. & Purcell, N. (2000). The Corrupting Sea: A Study of Mediterranean History. Oxford: Basil-Wiley.

Hurston, Z. N. (1928) ‘How It Feels To Be Colored Me’: thoughtco.com/how-it-feels-to-be-colored-me-by-zora-neale-hurston-1688772.

Kuus, M. (2017). Locating Europe’s power, or the difference between passports and passporting, Political Geography 60. 261 – 271.

Linebaugh, P. & Rediker, M (2002). The Many-Headed Hydra. Sailors, Slaves, Commoners, and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic. Boston: Beacon Press.

Lloyd, D. (2018). Under Representation: The Racial Regime of Aesthetics. New York: Fordham University Press.

Marbouef, O. (2019). ‘Decolonial variations. A conversation between Olivier Marboeuf and Joachim Ben Yakoub (May 2019): https://oliviermarboeuf.files.wordpress.com/2019/05/variations_decoloniales_eng_def.pdf

Matar, N. (2019). ‘The ‘Mediterranean’ through Arab Eyes in the Early Modern Period: From Rūmī to “White In-Between Sea”’, in The Making of the Modern Mediterranean. Views from the South, ed. Judith E. Tucker Berkeley: University of California Press.

Mbembe, A. (2017). Critique of Black Reason. Durham: Duke University Press.

Memmi, A. (2016). The Colonizer and the Colonized. London: Souvenir Press.

Proglio, G. (2020). The Horn of Africa. Diasporas in Italy. An Oral History, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Robinson, C. (2000). Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition, Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press.

Rovelli, C. (2016). Anaximander. Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing.

Rowland, C. (2020) ‘3 & 4 Will. IV c. 73’. Exhibition booklet, ICA, London, 29 January – 12 April: https://www.ica.art/media/03875.pdf.

Satia, P. (2020). Time’s Monster: History, Conscience and Britain’s Empire. London: Penguin.

Sharpe, C. (2016). In the Wake: On Blackness and Being. Durham: Duke University Press.

Shaw, W.M.K. (2019). What is ‘Islamic’ Art? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Steinberg, P. (2001). The Social Construction of the Ocean. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[1] https://floatsea.org

[2] For an excellent overview of the discussion on the Black Mediterranean, see chapter 4 ‘The Black Mediterranean’ in Proglio 2020.

[3] See also, Guy Mannes-Abbott, ‘Cameron Rowland, ‘3 & 4 Will. IV c. 73’’, Third Text: http://www.thirdtext.org/mannes-abbott-rowland