An Interview with Giancarlo Casale,

Rosita D’Amora

Salento University, Lecce

Giancarlo Casale is Chair of Early Modern Mediterranean History at the European University Institute in Florence, as well as a permanent member of the history faculty at the University of Minnesota. His new book, Prisoner of the Infidels: The Memoir of an Ottoman Muslim in Seventeenth-Century Europe will be released in summer 2021 from the University of California Press. Casale is also the author of award-winning Ottoman Age of Exploration (Oxford, 2011), and since 2010 has served as executive editor of the Journal of Early Modern History.

When we both started studying Ottoman history, this was not the most obvious choice of subject, especially for someone without a personal connection to the region. How did you get interested in Ottoman history and what have been the encounters, influences, personal choices and also fortuitous events that have shaped your intellectual and personal itinerary? Being an Ottoman historian, was it your ‘kismet’?

Complete kismet. Retrospective kismet, if there is such a thing. The truth is that I had no background at all in Ottoman history before beginning my PhD. I was originally a physics major as an undergraduate, but I failed out and ended up choosing history because I had already accumulated some credits, so it was a way of getting a degree without losing too much time. Of course, I could say that I was interested in physics because of a fascination with space and time and relativity, and was attracted to history as a way to study the same things without the math. There is some truth in this. But in the end, it was essentially a practical choice.

My subsequent encounter with Ottoman history was completely fortuitous too. When I decided to apply to graduate school, I had an astonishingly poor understanding of what doing a PhD might involve. I didn’t even really grasp, for example, that you were supposed to have a topic to propose as a dissertation! But it happened that my eventual advisor, Cemal Kafadar, was at that time planning to start a research project in Italy and thought it would be interesting for somebody who knew Italian and had a background in Mediterranean history to be studying with him. I was actually living in Padova, Italy, at the time, working odd jobs and because this was before email had really taken hold, in my application I had given my mother’s US phone number. Kafadar called my mother and the two of them more or less worked out the details on their own. I accepted without really knowing what I was getting into and, once I began, because my funding was based on the requirement of learning Arabic and Turkish, there was no turning back. I was like the Wizard of Oz on the balloon.

Another element of personal kismet is that, when I was born, because I have a relatively swarthy complexion, my grandmother called me u saracineddu, which means ‘the little Saracen’ in her dialect. Ever since, people have often assumed, from the way I look, that I am from the Middle East. So, who knows, maybe unconsciously this had something to do with my later choices in life.

This brings us directly to the next question. What do you think is the role that chance and serendipity play in your historical research and historical research more in general?

Historical research for me is almost completely serendipitous. This is not true for everyone. I see that for some of my colleagues and students, their idea of research is much more bureaucratic. You start by identifying a collection of documents, then you go and read the documents, and then you decide what sort of argument you can make based on that particular collection. But I never really have been able to do that. I always come across something by chance and, for some reason, it catches my attention. Later something else comes up that intersects with it and then I follow the lead. Maybe this is not a very good way to work, but…

As you know, this section of Cromohs is entitled ‘Historians and Their Craft.’ What is your personal definition of the historian’s craft? And what is the connection that you see between the craft of the historian and the contribution that historians can or should give to the understanding of the world we live in?

I think, first of all, that history is a very powerful discipline, much more powerful than we typically realise. At a fundamental level, everyone thinks about the world and tries to make sense of it, in terms of a story. This is just the way human beings’ minds work. So, whenever people ask really big, important questions, these questions are predetermined, consciously or unconsciously, by the stories about the past that they carry in their heads. And so, in the most general terms, the historian’s craft is to identify these stories and anticipate the way they predetermine the questions we ask about the world. And then, to the extent that it’s feasible, to open the door to asking questions in new ways, by changing the direction of these underlying stories.

I also think that Ottoman history is an incredibly interesting and challenging field for doing precisely this. As you know as well as I, over the course of our careers there has been a complete transformation in the way that people think about history in the part of the world that used to be the Ottoman Empire. You could even say that, until a couple of decades ago, Ottoman history didn’t really exist at all, in the sense that it was understood as a period of history instead of a field of history. One could study the Ottoman period of Bulgarian history, the Ottoman period of Turkish history, the Ottoman period of Egyptian history, and so forth, but there was very little sense that all these countries had a shared history as a result of once belonging to the same political entity. On the other hand, the one thing that almost everyone, working in all of these different national traditions, could agree on about the Ottoman past was that it was a failure, or a humiliating ‘dark age’ that should probably best be forgotten.

This perception has changed so dramatically, and so quickly, it’s almost breath-taking. Today, in most places that were once part of the Ottoman Empire, the relationship with the Ottoman past is now understood as an extremely active and evolving project, and one that deserves constant scrutiny and discussion. Of course, there is a dark side of that too, which is that the stakes have become much, much higher. I am sure you and I both have the same number of friends who have been politically blacklisted, or who can’t go back to their countries as a consequence. But if this is happening, it is precisely because history means so much more now in the public sphere than it did, say, twenty years ago.

Going back to the craft of the historian, there are lot of specific challenges that Ottomanists face and special skills that they have to acquire. In which way do you think those skills and those challenges are different from the skills that other historians use and the challenges that they face?

During my very first Ottoman Turkish class, my rahmetli (‘late’) Ottoman Turkish professor, Şinasi Tekin, told us that to learn Ottoman Turkish, we had to follow what he called ‘Mickey Mouse Rules.’ The first Mickey Mouse Rule was this: ‘If somebody, anybody, tells you they know Ottoman Turkish, it is bullshit!’ He said this last word with particular emphasis, pounding his fist, and then explained: ‘You cannot learn Ottoman Turkish, you can only learn to use the dictionary!’ Then he moved on to his second Mickey Mouse Rule, which was perhaps even more alarming: ‘If you see a word you don’t know, look in the dictionary. If you see a word you do know… look in the dictionary!’ And again, the pounding fist.

I am very grateful to Şinasi Bey for teaching me these rules, above all because they prepared me for something that is extremely difficult for people not already trained as Ottomanists to appreciate: the basic act of reading something, almost anything, in Ottoman Turkish is just so difficult. And the result, for so many of us, is this perpetual feeling of charlatanism. I can’t tell you how many of my colleagues, even some of my teachers, have privately admitted to having the same feeling I do whenever I sit in front of a new Ottoman document: that first moment when you are looking at it, and you are trying to make sense of it, and you just feel so devastated – because it’s your job to understand, but you don’t! It’s such a challenge at the basic level of comprehension.

Of course, this is something that is gradually changing over time, in part because of technology. We now have access to digital catalogues of archival collections, we can do keyword searches in the archives, more and more critical editions of manuscripts are being published, online dictionaries are becoming quite sophisticated, and so forth. All of this is transforming research, making it possible to absorb and to process sources much more quickly than used to be the case. But it is still true that the basic bar for entry in Ottoman studies, in the sense of just being able to understand what a source is saying, remains extremely high.

Compounding this is another factor, that you might call ‘pressure from the outside.’ By this I mean the rising interest in Ottoman history by scholars who are not specifically in the field. This is a quite recent development and overall a welcome one. But the fact is that scholars more familiar with, say, early modern European history, or contemporary global history, have expectations about the availability of sources and about the possibilities of doing research, that are simply not realistic in Ottoman history. The result is often a kind of embarrassment at not being able to fulfil these expectations, and a temptation to close yourself off in the little world of people who share the same challenges and difficulties, and can fully appreciate your work. This is, I think, something that you can see continually playing out in Ottoman history, this unresolvable tension between wanting colleagues from outside the field to pay attention, but at the same time resenting their basic lack of comprehension. At some level, I imagine this is an experience shared by specialists in most fields of non-Western, pre-modern history – fields which most Ottomanists haven’t tried hard enough to engage with, in my opinion.

On the other side, in Turkey, and not only, there seems to be a general craze for all things Ottoman. In recent years we’ve seen an explosion of Ottoman themed ‘dizi’ (‘Turkish TV serials’), historical novels, films, reconstructions, and video games, whose historical accuracy is often quite dubious. What do you think about these media and about unorthodox ways of dealing with history? Is it possible to convey historical research differently?

I think this evolving media ecosystem is changing the way we think about narration fundamentally, and by no means only for Ottomanists. The old idea of a self-contained book – which you, as an author, have control over, obliging your reader to follow you from the beginning to the end – that model just isn’t operative anymore. Now, rather than reading a book from cover to cover, most people read a bit of something, they stop to google a word, they see a link and click it, this takes them to a video they decide to watch. Then, if you’re lucky, maybe they go back to your book. Like it or not, this is the way people experience and absorb information. And so, it only makes sense that we should try to rethink the way that we work as historians with this in mind. Expectations are fundamental to the way that we present our historical research. If we can’t work with people’s expectations, they won’t understand what we’re doing – another version of the same problem we just discussed with respect to our non-Ottomanist colleagues.

To this end, I’m in the middle of writing a short article with a colleague, Nicolas Trépanier, on what videogames can teach about history. For me, the entry point is the realisation of just how important video games have become for my own students’ developing understanding of history. And while some might see this as a problem, I see it as the source of all kinds of new possibilities. To give just one example: when I first started teaching, there was clear expectation that the further away from ‘here and now’ you went in time and space, the less interesting and meaningful history would be for students. And you could see this clearly in hiring practices and in the way that academic departments were structured, especially in the United States. Almost everybody was doing twentieth-century history and all the classes were about identity, politics and contemporary topics that students didn’t have to work very hard to connect to. Recently, however, I can see a very different trend emerging: the further away in time and space you go, the more students are curious and engaged. And I think that video games have a lot to do with that, because they really help you to see long sweeps of history, to reconstruct realities of the past vividly and immersively, and to test counterfactuals in very sophisticated ways. That kind of experimentation is inherently fun, but especially when it takes place in completely new, distant, and unfamiliar environments. It’s another way to travel in space and time, to go back to the counterfactual physicist Casale from the beginning of this interview.

Of course, there is another important element to consider here, which is that the ‘real world’ outside of videogames doesn’t feel quite as real as it used to – a feeling that has been accelerated by COVID, but was already very present beforehand. The first time I travelled to Istanbul, for example, in 1997 – and you were there too, Rosita, so I’m sure you remember – we were completely immersed in that reality. There was no iPhone that you could carry around in your pocket. No GPS to help find your way. No translating app. There wasn’t even anything to watch on TV besides Turkish shows, or anybody to talk to that wasn’t a Turkish person. And that was, for me, the most intense intellectual experience that I have ever had: the experience of being in an unfamiliar place, completely cut off from everything that I knew, and forced to somehow make sense of the world. But that kind of experience just doesn’t exist anymore. I have since led groups of my own students on study abroad, and they have spent the whole time texting with their friends back home, sending selfies back to their parents, and so forth. It’s like they are physically present in a foreign country only in a very partial and attenuated way. But ironically, when they play a video game, they are completely in the video game. A good game is too absorbing to stop and text your friends or take pictures of yourself. So, it turns out real life isn’t immersive in the same way that a video game is. I find that completely fascinating and something that needs to be taken seriously.

Your writing style is very captivating, accurate, and rich. It is also very entertaining and, sometimes, you include unexpected personal details, such as references to some not entirely flattering reviews you have received. Should history writing be entertaining? Or is there a risk of not being taken seriously?

It absolutely is a risk. In fact, someone once said this to me directly. I was, I think, in Germany, giving a lecture and, as soon as I finished, somebody raised his hand and said: ‘Well, thank you for this talk. It was very enjoyable. In fact, it was so enjoyable that I feel it must somehow be wrong.’ So there absolutely is an idea that the more boring something is, the more credible it is. And this makes a certain amount of sense, because if you’re trying to get attention, then the obvious way to do that is to sacrifice accuracy for entertainment value, to tell people a good story without worrying about whether it’s true or not.

In this respect, history writing is a kind of spectrum. On one end of the spectrum is a historical novel, which is trying to be evocative and compelling without a claim to factual accuracy. And the opposite end of the spectrum would be, I guess, a bunch of documents that bore you to death. Neither of these extremes counts as a work of history, yet every historian has to wrestle with where to come down on the spectrum that lies between them. And this is a choice that has particular implications for Ottoman historians, due to one of the dirtiest secrets of the field: a lot of Ottoman documents are boring, really boring. When you stop to think, it’s almost cruel: millions of documents that are unspeakably difficult to read, but when you finally manage to understand them, they bore you to tears.

Now, why exactly are most Ottoman documents ‘boring’? I would say that it’s because, in a systematic way, they avoid recording individual lived experience. This is a reality that was made extremely clear to me while doing research for my book about the Indian Ocean, for which I divided my time between the Ottoman archives in Istanbul and the Torre do Tombo archives in Lisbon. In Istanbul, I was mostly reading the Mühimme Defterleri (‘Registers of Important Affairs’), in which were copied all of the important orders issued in the Sultan’s name and sent out into the world. Day after day, you can look through these registers and essentially read the Sultan’s outgoing mail. Often, you also have references to letters that are coming in, from which you can see that people are continually writing from all over the place. But these letters are not recorded: only the bureaucratic response of the central government was considered worthy of being entered into the record. The Portuguese archives, meanwhile, are almost the opposite. In the Corpo Cronológico, for example, you have literally thousands of letters from people stuck in some God-forsaken fort somewhere, trying to convince the central government to do something. They write about the things they have seen and done, the rumours they have heard, their hopes, their regrets. It’s all about self-presentation as a way of activating the attention of the people who make decisions.

For the most part, Ottoman archival sources just aren’t like that. There are, of course, exceptions. But as a system – at least when speaking about periods before the nineteenth-century – the Ottoman archives seem to resist recording information in this way. Take, for example, the sicils, or Ottoman court records. There are thousands upon thousands of these from throughout the early modern period, and recently they have garnered a great deal of attention, and generated lots of excitement, because of all the possibilities they offer for new kinds of historical research. And they are, indeed, extremely rich sources with all kinds of applications. But compare a sicil with a case file from a typical early modern European court of law, or a related source like an inquisition file, and you immediately realise that you are dealing with documentation of a completely different order. In a typical sicil, you have almost no actual testimony, or opposing versions of events offered by the litigants, or theories of the case presented by advocates. Instead, you essentially have a brief synopsis composed by a judge or a scribe, summarizing the case, with barely a trace of the individual litigants’ voices. This is a huge limitation on an empirical level. But just as important, I don’t think that, as Ottomanists, we have thought enough about why, exactly, our archives are built this way.

Could the acknowledgment of such a limitation benefit Ottoman historical research?

Yes, absolutely. Plenty of other fields have richly benefitted from a heightened awareness of the archive and its limitations. Postcolonial studies, for example, was essentially born out of a recognition that, in places like South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, there really weren’t any archives except for those built by foreign, colonial empires. And this recognition posed the problem of how to write history without reproducing the perspectives and the hierarchies that the colonial authorities had inscribed into their archive – leading to a critical re-evaluation of the very nature of historical research, the need to read sources against the grain, and so forth.

In Ottoman history, this didn’t really happen. Instead, the attitude has sort of been ‘Wow, that’s too bad for those poor South Asians and sub-Saharan Africans, who don’t have their own archive. Luckily for us, our archive has 100 million documents!’ So, there is this fetishisation of documents and this idea that the ‘completeness’ of a historical study is in direct proportion to the number of archival sources one puts in the footnotes. I find this attitude extremely frustrating, although I’m also encouraged by some recent work by a younger generation of scholars who are clearly moving in new and different directions.

This brings us right to your latest work, Prisoners of the Infidels: The Memoir of an Ottoman Muslim in Seventeenth-Century Europe, which is a study and full English translation of the remarkable autobiographical account of Osman Agha, enslaved during the Ottoman-Habsburg Wars. Who was Osman Agha? And what was it about him that made you shift your attention, until now deeply rooted in the sea and sea exploration, towards central Europe?

As you say, Osman was a young Ottoman soldier who was taken prisoner and held captive by the Habsburgs for more than a decade. In this respect, he was no different from thousands of other Ottoman prisoners of war. But for some reason, after his safe return home, Osman got the idea of composing a full, book-length account of his experience abroad, including his impressions of his captors and their country, the details of his escape, and even his struggles to reintegrate to life back home.

For someone unfamiliar with Ottoman historical sources, this might not seem particularly unusual. There are, after all, literally thousands of first-person accounts by early modern Europeans who travelled to the Ottoman Empire as captives, or merchants, or diplomats, and there is a basic expectation among European historians that the same must be true in reverse. But it really isn’t. There are only a handful of very short Ottoman captivity narratives that predate Osman’s and none of them have anything approaching the narrative voice or the level of detail and introspection of Osman’s account.

Just as important, Osman’s memoir is more than a captivity narrative, since it recounts his entire life from the time he was born until well into the 1720s, more than two decades after his safe return to Ottoman territory. In this sense, it is a bona fide autobiography, and a very sophisticated one at that. It is earthy, and funny, with more than its share of plot twists and moments of high drama. But it also addresses extremely profound questions about the fragility of personhood, self-discovery through alienation, and the impossibility of ever truly ‘returning home’ after enslavement.

In short, Osman’s memoir is a precious source in its own right, but doubly so because it provides what the Ottoman archival record so often resists: an account by an individual, who records in his own words his experiences, his observations, his feelings, and his aspirations in the form of a completely coherent narrative. And who knows? Maybe some of the things in his memoir didn’t actually happen, but were included just for the sake of a good story.

As you mention in your introduction to Osman Agha’s memoir, this text has already been translated in several languages. Besides making it available to an English-speaking audience, why did you decide to present a new translation of the text? And, more generally, what do you think is the role of translation in historical practice? Is the importance of translation often overlooked?

I believe translation is one of the most creative intellectual activities that exists. If you think of the Renaissance, this basically started as a translation movement. The same could be said of what we used to call ‘Islamic Civilization,’ which began, again, with a massive translation movement. And yet, historians have a conflicted relationship with translation. On the one hand, anyone who works as a historian, except for a few colleagues focused narrowly on their own national history, necessarily has to use sources in different languages. Despite this, there is a deeply held belief that translation is not really creative work – a machine could have done the job just as well. In fact, this belief is embedded in the professional structures of our discipline: If you paraphrase or summarise a group of historical documents, adding some notations and a bit of analysis, no one would question this as an original work of history. But if you carefully translate the same documents, again with some notes and analysis, you’re likely to get no professional credit at all! Frankly, I find this outrageous. Translation is one of the deepest ways of engaging with historical sources: a complex process through which we recognise that words from a different time and place do not have quite the same meaning that they have for us, requiring us to re-insert them into a rich historical context to fully understand. That’s the very essence of history, from my perspective.

As for my specific interest in translating Osman Agha, I obviously wanted to make his writing more accessible and to encourage readers to think about his memoir as a really creative and original work of literature, rather than simply a ‘source.’ But that was really only one small part of the motivation. I was just so curious to try to learn how someone like him, with essentially no cultural models to guide him, could have written such a complex and sophisticated autobiographical text. So I decided to try to understand his writing as completely as possible, and the most obvious way to do that was to go through it meticulously and grapple with it word by word. Finally, I have to say that I also just really like the guy. You have to enjoy spending time with somebody to translate their writing.

I will confess one more thing about my reasons for doing a translation. Over the years, I’ve lost a little bit of confidence in my ability to communicate through historical narrative, partly from the experience of having some of my arguments systematically misunderstood by colleagues. To be clear, I’m not necessarily referring to critics: sometimes, it was rather the people who were ostensibly my most enthusiastic supporters that I could see attributing things to me that I hadn’t actually said, or at least not in a way that I had intended. And somehow, I felt that a translation could perhaps be less open to misunderstanding. In other words, by helping somebody else to communicate with his readers across a distance of several hundred years, it made me feel less ambiguous about my own ability to make a historical contribution. So, absolutely, we should be translating more and we should all get more credit for doing it.

What are you currently working on?

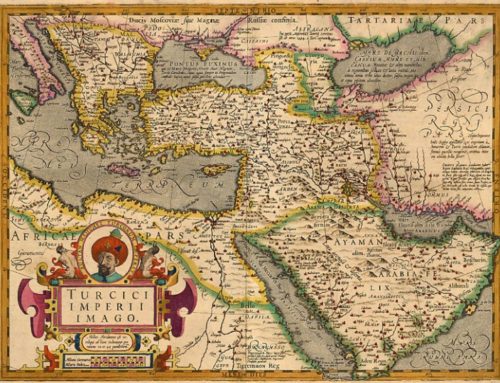

For more years than I can count, I have been ‘finishing’ a book about the connections between intellectual life in the Ottoman Empire and the thought world of the Italian Renaissance. The book basically involves a series of biographical chapters focused on different people who lived in the Ottoman Empire between the middle of the fifteenth and the end of the sixteenth century: a Greek philosopher, a sea captain, a judge, an architect, and so forth. What connects them is that all were engaged in various ways with the idea that the Ottoman Empire was the ‘new Rome’ and to that end were either translating texts, or writing histories, or describing monuments, or engaging in various kinds of mapping. I focus systematically on architecture and maps alongside texts, because these are two media that can be used to communicate very sophisticated ideas, particularly about time and space and sovereignty, between people who don’t necessarily share the same language.

One of my last chapters is about an Ottoman madrasa professor who compiled an encyclopaedia of world geography toward the end of the sixteenth century. It is, to be honest, about the most unoriginal and intellectually cowardly book you could possibly imagine, in which he describes the state of knowledge about the world in his time as if it were unchanged since the fourteenth century: no discovery of the New World, no circumnavigation of Africa, etc. He clearly knew better, but he apparently wrote what he did in the hopes of pleasing his superiors so they would give him a promotion – and they did. But then he spent the next fifteen years rewriting his book not once but twice, each time introducing progressively more radical ideas about the world and how the understanding of it was being transformed. Eventually, he was fired from his academic position and shipped off to work as a provincial judge. Thereafter, the last and most innovative version of his book was forgotten, while the earliest version was recopied hundreds of times, such that he was later remembered for having written only that one.

This might tell you something about the way I’m thinking about my own work, and how I expect to be remembered in the future.

Transcription of the interview by Wesley Lummus

First published in Cromohs 23 (2020)