Perched on a promontory along the Corniche in Marseille’s salubrious quartiers sud, the Monument aux Héros de l’Armée de l’Orient et des terres lointaines represents an ambiguous lieu de mémoire of conflict and colonialism. Built to commemorate those who died while serving in French forces during the First World War on the Balkan fronts, at the Dardanelles, and in colonial spheres of the conflict, the monument, commonly known as the Porte d’Orient, does de-centre the Western front in commemorative discourse and underline the global nature of the conflict. However, the symbolism embedded in the sculptural form of the monument and the subsequent commemorative interventions on the site elide the centrality of coercive system of colonialism to the histories of violence it claims to memorialise. This selective silence raises broader questions about cosmopolitan modes of commemoration on the Mediterranean’s Northern Shore, both past and present, that elevate limited conceptions of diversity over the harsh realities of domination and discrimination rooted in colonialism and the resistance which they have provoked.

Marseille’s status as the principal port of the French empire is embedded into the built environment of the city. The most emblematic and controversial example of the monumental staircase leading to the Gare Saint Charles, the city’s principal train station. This celebration of the city’s central role in the imperial project includes two racialized and exoticized sculptural representations of France’s colonial possessions in Asia and Africa that serve to legitimise and romanticise the whole colonial enterprise and have been the subject of critique from activists in the city in recent years. The staircase represents a permanent expression of the city’s colonial mission that had temporarily been embodied in the Colonial Exhibitions of 1906 and 1922, events that projected French imperial power through the direct exploitation and exhibiting of colonial subjects. Originally planned to be completed in time for the Colonial Exhibition in 1922, the project was pushed back due to the outbreak of the First World War, and was thus contemporaneous to and, entangled with the construction of the city’s major war memorial. Both were inaugurated on the same date, April 24 1927, with the archival photographic record of the ceremony at the monument on the Corniche noting that the delegation of dignitaries had earlier performed a similar ritual at the staircase. (Figure 1). Though the war memorial eschews the kind of racialised open celebration of colonialism that defines the staircase, it was, from the outset, integrated into the broader cultural project of presenting Marseille as the node of France’s empire.

Figure 1: The inauguration of the monumental stairway at the Gare Saint Charles. Archives Municipales de Marseille, 54 Fi 35.

When France turned to its empire for both material and men following the outbreak of the First World War, Marseille would prove central to the logistics of the colonial contribution. In the initial stages of the mobilisation, it was the port of entry for the contingents of the Army of Africa, a body of units drawn from the settler communities and from the populations of France’s North African colonies. As the war dragged on and France’s recruitment efforts intensified across the empire, especially in West Africa, ships carrying thousands upon thousands of men destined for the battlefields or the war industries were directed towards Marseille. The city’s docks were staffed in part by colonial workers from Indochina while the surrounding region was used for the ‘wintering’ of colonial troops from tropical climates. Marseille also hosted postal control centres where officials trawled through the correspondence of colonial troops and workers, censoring expressions of discontent, anti-colonial sentiment, and accounts of illicit encounters and/or romantic relationships with French women. Beyond the control of the civil and military officials, the city was the site of all kinds of encounters for colonial subjects with metropolitan citizens, other Europeans, and other inhabitants of the empire. While the multi-layered experiences of those colonial subjects who served in France during the war, the conditions of their recruitment, and their contribution to the war effort have all been the subject of a rich and expanding historiography, the service of colonial subjects on the other fronts of what was a global war has received less attention. And yet, thousands of the men from the empire who passed through the port of Marseille, both settlers and subjects, did not disembark to travel to the trenches of Northern France. Instead, they transferred to other ships bound for distant battlefields, especially those in the Balkans and at the Dardanelles, where they fought in challenging conditions, with many making the ultimate sacrifice. These are the men that the monument on the Corniche aspires to commemorate.

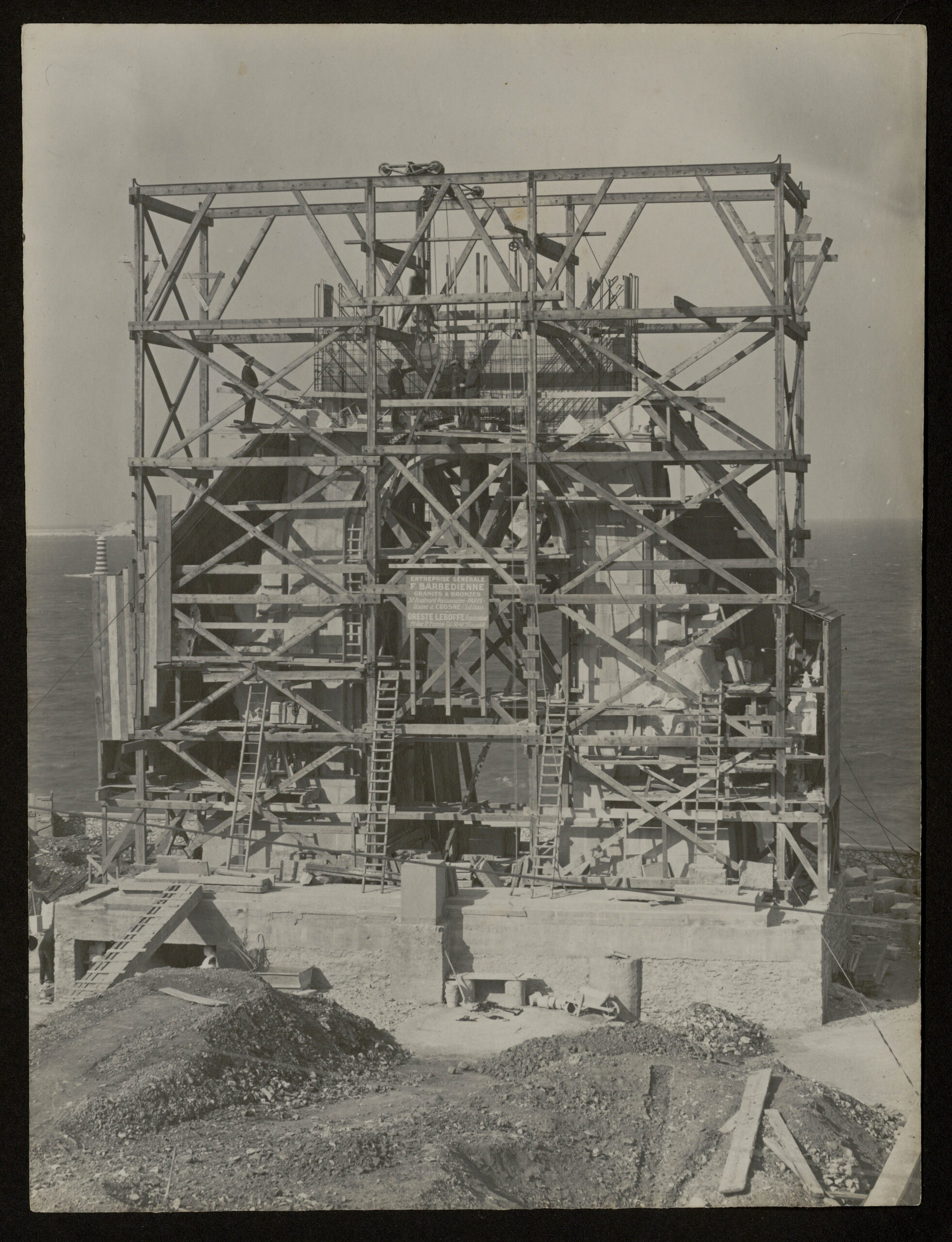

The origins of the monument date back to 1924, when a competition was launched for a commemorative sculpture in honour of the soldiers and sailors who had died on fronts other than the Western Front. The jury awarded the commission to local architect Gaston Castel, a veteran and former prisoner-of-war who had led the reconstruction of the Marseille Opera house that same year, and Antoine Sartorio, a fellow veteran specialising in monumental sculpture. Their project envisaged a triumphal arch with representations of soldiers on each flank following a winged Victory. In front of the arch, a sculpture of a female allegory of France would embody the joy of the nation at the announcement of the armistice. The monument was to be located on the Corniche, the seafront avenue that hugged the coast to the east of the centre of Marseille. The site was cleared and construction under the direction of Castel began in earnest in 1926 while Sartorio worked on the sculptural elements in his studio. The triumphal arch began to take shape in late 1926/ early 1927 (Figure 2), with the whole memorial complex completed in time for the inauguration in April 1927.

Figure 2: View of the construction site of the monument from February 1927, Archives Municipales de Marseille, 54 Fi 20.

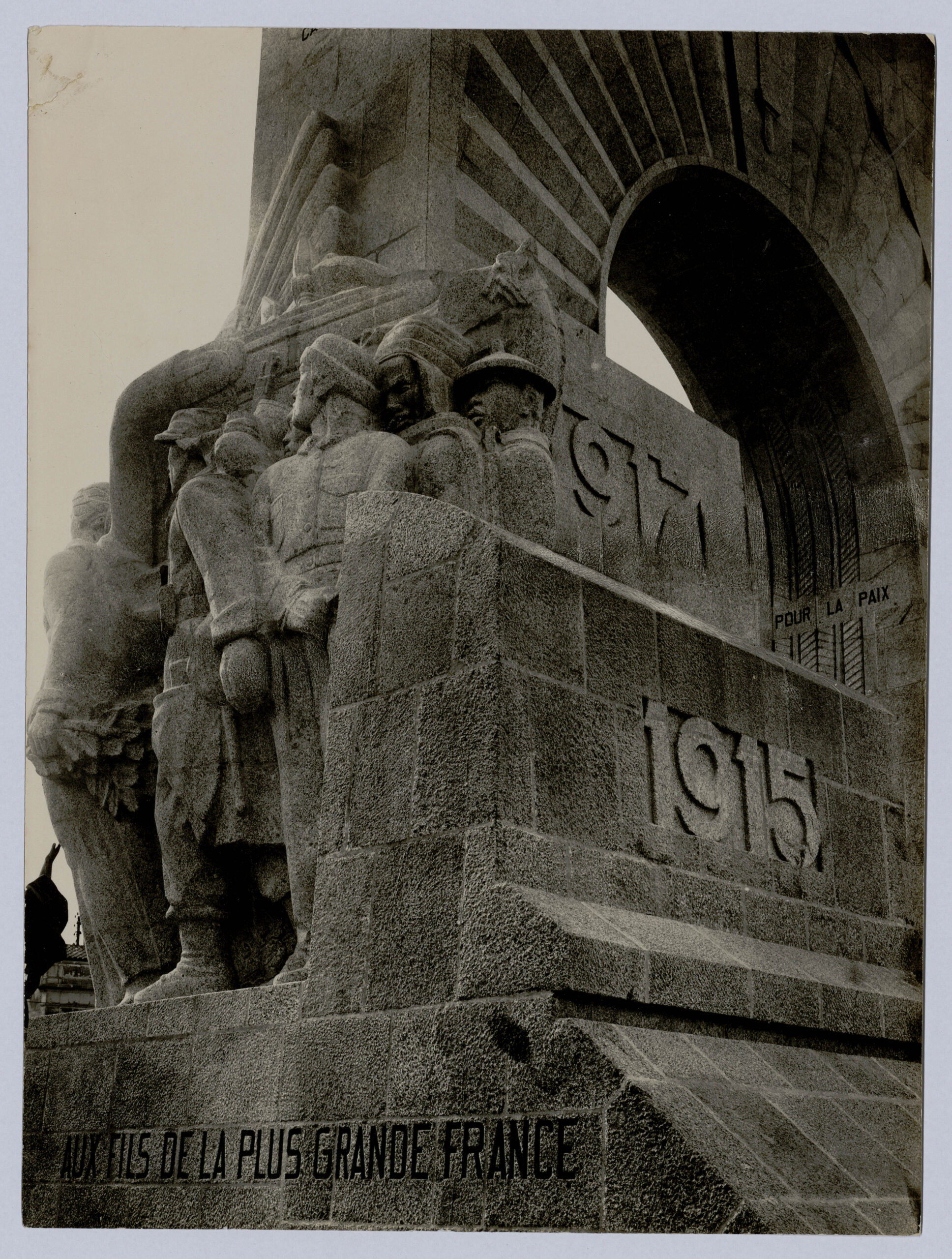

The two flanks of the monument represented two quite distinct elements of the commemorative narrative. The eastern flank was specifically dedicated to what the French called the Eastern Front. It included a list of the major zones of conflict in the Balkans and the Dardanelles and the dedication ‘Aux Poilus de l’Orient’, using the affectionate nickname given to French infantrymen (Figure 3). Among the group of soldiers and sailors represented on the eastern façade, we do note one figure wearing what appears to be a chéchia, a North African hat, decorated with the star and horizontal crescent moon that was the symbol of the Army of Africa. Hats like these were part of the uniform of both colonial subjects and colonial settlers from North Africa serving in units of France’s ‘Armée de l’Afrique’. This representation does underline the colonial contribution to the war effort on the Balkan fronts and in the Dardanelles, but the ethnic ambiguity of the figure in question means that we cannot be certain that either the intention or the effect of his inclusion was to honour those colonial subjects who, denied rights within the imperial polity, fought to defend it.

Figure 3: Eastern flank of the Monument aux Héros de l’Armée de l’Orient et des Terres Lointaines. Archives Municipales de Marseille, 54 Fi 28.

The western flank of the monument is much more explicit in commemorating colonial subjects’ involvement in the war. Dedicated to the ‘Sons of Greater France’, the sculptural representation includes what appears to be a colonial soldier in a combat uniform followed by clearly identifiable troops (tirailleurs) from West Africa, North Africa and Indochina (Figure 4). The vision here is one of imperial unity, showing colonial soldiers rallying behind a winged victory to defend the Patrie. The reality of the coercion that accompanied practices of recruitment in the colonies, as well as the numerous anti-colonial rebellions that occurred during the war is completely elided here. Above these exoticised portrayals typical of the period we see a list of non-European spheres of conflict: Morocco, the Levant, Syria, Cilicia, and Cameroon (Figure 5). This juxtaposition is interesting in and of itself as it seems to conflate, at least in commemorative terms, the contribution of colonial troops, most of whom fought on European battlefields, with the colonial spheres of conflict themselves, with Otherness the main uniting category. The inclusion of Morocco here is striking in that unlike on the Middle Eastern Front, where the French and their Allies were facing off against the Ottomans, and in Cameroon, where French and British colonial forces fought the German Schutztruppe, the enemy against which French troops were fighting in the recently declared protectorate was in fact the putative ‘Sons of Greater France’ themselves. The conflict in Morocco predated the war, its origins lying in French invasion in 1911 and subsequent expansion, which met with fierce resistance. It would long outlast the war, with the Armistice celebrated in the monument not signalling an end to armed resistance to the French and the concomitant deaths of soldiers in French uniform (typically colonial subjects) in Morocco. The image of a united colonial family rallying to the cause of France was thus called into question within the commemorative monument of the language itself.

Figure 4: Western flank of the Monument. Archives Municipales de Marseille, 54 Fi 30.

Figure 5: Western flank of the monument with list of spheres of conflict. Author’s photo

Subsequent additions to the monument would further underline the tensions at the heart of both the colonial project and commemorative discourse. The plaque commemorating French colonial rule in Indochina that was erected alongside the statue celebrating the Armistice present a selective and reductive vision of colonial history (Figure 6). Rather than simply commemorating the war that ravaged Indochina from 1946 to 1954, ending in the humiliating withdrawal of the French and the triumph of the Vietnamese, it offers a different chronology, embracing the longer period from 1624 to 1956 that it describes as ‘three centuries of French presence’. During this period, it affirms that the ‘a solemn pact’ between ‘the French and the peoples of the Indochinese Union’, a creation of French colonial rule, was ‘sealed in spilled blood’. Here the sacrifice of the First World War, commemorated in the main monument, is tied into a broader colonial narrative of French sacrifice in Indochina that retrospectively sanitises and justifies French rule.

Figure 6: Monument to the French Presence in Indochina. Author’s photo.

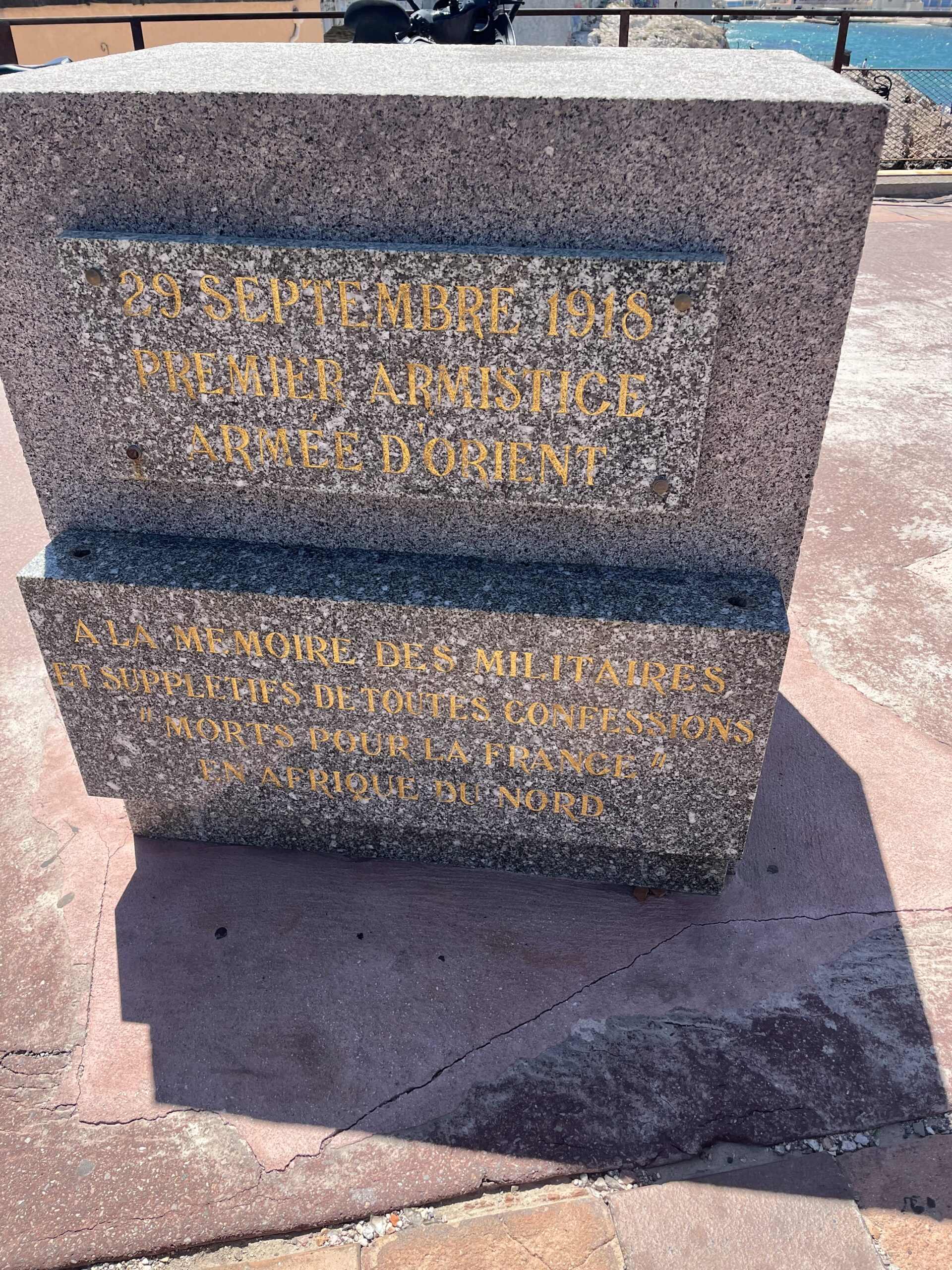

A similar sanitisation is evident in the nearby plaque dedicated to the ‘members of the military and suppletive forces of all religions who died for France in North Africa’ (Figure 7). In line with what was a longstanding French policy, reference to ‘war’ in Algeria was studiously avoided in the plaque and the decolonising essence of the conflict was obscured.

Figure 7: Monument to the memory of members of the military and suppletive forces of all religions who died for France in North Africa. Author’s photo.

The dedication ‘Hommage to the harkis’ affixed to the back of the triumphal arch does not address either violent actions of those who served the French state in Algeria nor their severe neglect at the hands of the French state after the conflict ended (Figure 8). These commemorative interventions underlined that the political function of the space was not solely or even primarily to honour those from the colonies who died in conflict but rather to mobilise their sacrifice in defence of a vision of the colonial past (and its presents) that is strangely stripped of its inherent violence.

Figure 8: Plaque in homage to the Harkis. Author’s photo.

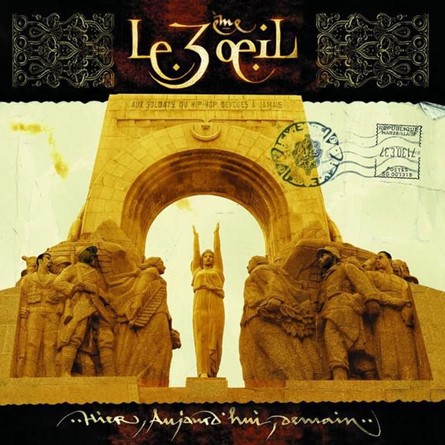

The dominance of this sanitised and glorifying narrative within the monument has been challenged by artists in Marseille. The presence of the monument on the cover of the best-selling rap album ‘Hier, Aujourd’hui, Demain’ released in 1999 by the group 3ème Oeil, two rappers from Marseille’s post-colonial Comorian community, was an act of symbolic appropriation that asserted ownership of the city by the descendants of those the memorial claimed to commemorate. The photomontage on the cover re-configured the monument, placing the sculptural groups from the flanks in the foreground and re-imagining them as representing not exoticized and anonymised visions of colonial troops but rather as the ascendants of the contemporary racialised and multicultural populations of Marseille. The dedication across the top of the arch was altered, with the monument no longer honouring ‘The Soldiers of the Army of the Orient and Distant Lands’, now celebrating instead ‘The Eternally Devoted Soldiers of Hip-Hop’. These post-colonial sons of Marseille were reclaiming the monument as their own.

Figure 9: Cover of Le 3ième Oeil’s album Hier, Aujourd’hui, Demain, 1999, Columbia.

More recently, the growing critical engagement with symbols of colonialism in the public space have seen artistic interventions that interrogate the monument’s colonial commemorative narrative. Marine Schütz’s work has detailed how the Marseille-based Moroccan artist Mohammed Laloui has integrated the monument into his artistic interrogations of the legacies of colonialism. His series ‘Ex-votos’, which involved him doing live tracings of some of the commemorative plaques at the monument critiqued the discourse of gratitude towards colonialism embedded in the memorial complex. His subsequent exhibition in Rabat used the Marseille monument as one of a series of points of departure for a broader critical discussion of the persistence of the colonial in public spaces on both sides of the Mediterranean. Laouli was a contributor to the 2020 exhibition Rue d’Alger hosted in the Italian Cultural Institute in Marseille that offered a broader artistic engagement with the cultural legacies of colonialism in the city’s public space. Featured alongside Laouli’s work, the artists Emma Grosbois and Agathe Rose’s series ‘20 Tonnes of Bronze, 215 of Granite’ ties together the history of the monument and the more recent Memorial to the Repatriated of Algeria (1971) that is located four kilometres to the west along the Corniche and honours the settlers of Algeria who left for France in the period of decolonisation. By juxtaposing images and accounts of the development of both monuments, they expose the continuities in colonial commemorative discourse over time and the enduring occlusion of critical voices and representations from the urban space in the city. The monument has thus become a lightning rod for a growing interrogation of the coloniality of commemoration in public spaces in a city where large swathes of the population of descended from those who were oppressed by colonial rule and continue to grapple with its legacies in the structures of exclusion that shape life in Marseille.

The Porte d’Orient thus offers a unique window into the shifting meanings of the commemorative culture developed around a conflict that was not only total and global but also profoundly colonial in nature. The discourse of imperial unity embodied in the monument’s sculptural representations, compounded by the subsequent memorial interventions obliquely commemorating the wars of decolonisation, fundamentally occlude the logics of violence and conflict under colonial rule. Alternative discourses that have emerged in recent years, particularly around the Centenary of the Great War, grounded in highlighting the diversity of the troops that fought for France avoid the direct reproduction of the exoticising depiction and racist hierarchies that underpinned the notion of the imperial family. And yet, unless they comprehensively account for the regimes of coercion that shaped colonial participation in the war and that underpinned the broader colonial system, they cannot form the basis for a truly shared commemorative discourse. The critical interrogations led by artists show us a potential path out of the dead-ends of selective silences and towards an honest discussion about the colonial pasts and its presents.

The research for this visual reflection was conducted during a Short Term Scientific Mission funded by PIMo and conducted in partnership with Dr Randi Deguilhem of the Université Aix-Marseille.

Biography

Dónal Hassett is a colonial historian of the French Empire with a special interest in North Africa. A Lecturer in the French Department at University College Cork, he is also the Science Communication Officer for the PIMo COST Action. He was recently awarded a European Research Council Starting Grant for a comparative project on colonial veterancy in the interwar period.

Bibliography

Robert Aldrich, ‘Memorials to French Colonial Soldiers from the Great War’, https://crid1418.org/doc/textes/aldrich.pdf

Christophe Asso, ‘Emma Grosbois & Agathe Rose: La fabrique du monument’, Photorama Marsellie, 14/11/2021, https://photorama-marseille.com/emma-grosbois-agathe-rosa-la-fabrique-du-monument/

Laurent Noet, ‘Autour de Gaston Castel. Promotion d’une sculpture monumentale parlante à Marseille’, In Situ. Revue des patrimoines, Vol.32, 2017.

Le 3ème Œil, Hier, Aujourd’hui, Demain, Columbia, 1999.

Christelle Rabier, ‘Vestiges d’Empire : Recension de Pierre Sintès, dir., Rue d’Alger, Art, mémoire, espace public, éditions MF 2022’, 2023.

Marine Schütz, ‘Rewriting Colonial Heritage in Bristol and Marseille: Contemporary Artworks as Decolonial Interventions’, Heritage & Society, Vol.13, Nos.1-2, 2020, 53-74.