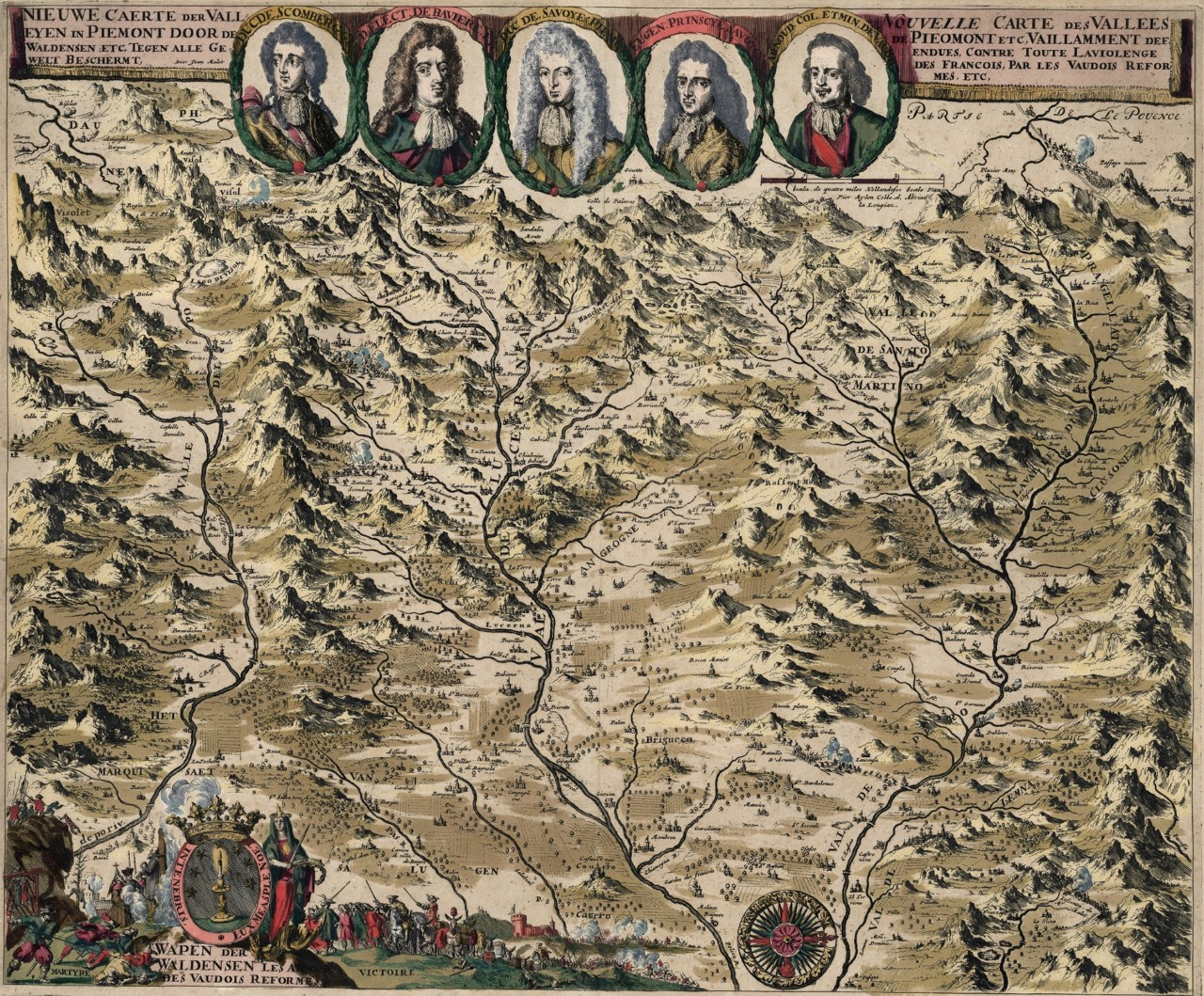

The gaze ranges over the territory of the three valleys of western Piedmont, now known as ‘Waldensian’ – because of the centuries-long presence of the Protestant minority of the same name in the heart of the Alps – ensconced between high mountains overlooking a plain seen from a bird’s eye view, crossed by three main waterways, and dotted with villages and hamlets.

Entitled Nieuwe Caerte der Valleyen in Piemont door de Waldensen and printed in 1691 in Amsterdam by Joachim Ottens, the map provides a detailed depiction of the territory of the Pellice and Germanasca-Chisone valleys, including the Po valley. (Fig. 1)

Figure 1: [Romeyn de Hooghe], Nieuwe Caerte der Valleyen in Piemont door de Waldensen, [1691]; H476mm, W572mm (Torre Pellice, Museo Valdese, property of Archivio della Tavola Valdese). © Courtesy Museo Valdese, Torre Pellice

Both from the layout of the representation and most of the topographical information, the descriptive model for the map can be seen to be the Carta delle Tre Valli di Piemonte. Dated 1640, it is known only in a printed version signed by Valerio Grosso (ca. 1585–1649/50), a Waldensian minister native to Bobbio Pellice, one of only three ministers to have survived the plague of 1630. It is the first cartographic portrayal of the territory inhabited by the Waldensians, who produced it 15 years before the massacre in 1655 by the troops of the Duke of Savoy upon the desire of the regent Marie Christine de France. The event is best known as the ‘Pasque Piemontesi’ (Piedmontese Easter) or ‘Primavera di Sangue’ (Bloody Spring). The map circulated widely, both reproduced in printed works and as a model replicated in subsequent papers, until the nineteenth century. Its first printed reproduction dates back to 1658, when it was included in The History of the Evangelical Churches of the Valleys of Piemont (London 1658) by English ambassador Samuel Morland, followed 11 years later by the Histoire générale des Eglises Evangeliques des Vallees de Piémont; ou Vaudoises by Waldensian pastor and moderator, exiled in the Netherlands, Jean Léger – accompanied by the Waldensian coat of arms and the cartouche ‘Convallium Antiquissima Insignia.’

If Grosso’s map of 1640, published first in London and then in Leiden, for the first time expressed a territorial identity on the part of the Waldensians in the dramatic situation of the mid-seventeenth century, the political significance of the Nieuwe Caerte der Valleyen was set against the backdrop of a new event of great importance in the history of the minority.

With the Edict of Fontainebleau of 18 October 1685, which revoked the conditions granted to the subjects of the reformed confession in the Edict of Nantes, the Waldensians in the valleys of Piedmont – first those living on the left bank of the Chisone river (at that time under French rule), then, through a similar initiative of the Duke of Savoy Victor Amadeus II, also those in the adjacent valleys – experienced a new season of persecution. Refusing to abjure, after attempts at armed resistance, thousands were jailed in the prisons of Savoy and then, thanks to the intervention of representatives of the Swiss cantons, welcomed as exiles and partly sent to other Protestant lands, in particular Brandenburg, Palatinate and Württemberg. After two attempts, just under one thousand men managed to return to their native valleys in 1689 and then, thanks to the Duke of Savoy’s change of alliance in June 1690 and the support of the Protestant potentates, the Waldensians’ rights and possessions were officially reinstated in 1694.

The Waldensians received extensive political, diplomatic, economic and military support in those years, especially from England and the United Provinces, where propaganda, not only in print, was widespread and made a great impression. The massacres of 1655 had also aroused emotion and apprehension in the Dutch public, thanks to the circulation of broadsheets, gazettes and chronicles of the events. Some were also accompanied by pictures, as in the case of the Wreede vervolginge En schrickelijcke moordt Aende Vaudoisen, Jn Piedmont geschiet in Iaer 1655 Ofte Droevige tijdinge over ’t onnosel bloet vande Gereformeerden vergoten door den Hartoog van Savoyen (Cruel persecution and horrendous massacre of the Waldensians in Piedmont in the year 1655, or Sad news about the innocent blood of the Reformed poured out by the Duke of Savoy), printed in the same year by Jacob Cornelissz and illustrated with seven woodcuts with scenes of capture, imprisonment, hangings, burnings and killings. In the same year, Jodocus Hondius printed a large-format manifesto entitled Growlyke wreede moord en vervolging, aan de Vaudoisen, in Piemont (Cruel and atrocious massacre of the Waldensians in Piedmont), divided into sixteen frames depicting the massacres, accompanied by a legend and a map of the Waldensian valleys.

In 1669, in Leiden, Jean Le Carpentier printed the aforementioned Histoire générale des Eglises Evangeliques des Vallées de Piémont by Jean Léger. He also printed Grosso’s map containing 26 scenes of the massacres perpetrated against the Waldensians in the valleys in 1655 which had already been proposed 11 years earlier in Morland’s book.

The presence of images of persecuted Waldensians in Dutch prints continued after 1685, even though compared to the great exodus of French Huguenots, they played a background role in the polemics concerning the policy of the king of France against the Reformed. Amsterdam-born engraver and illustrator Romeyn de Hooghe, closely linked to stadtholder William III of Orange, later King of England, is credited with the satirical manifesto entitled Mardi gras de cocq a l’ane, a carnivalesque poem in verse also including a character explicitly referred to as ‘Waldensian,’ to show the consequences of the French anti-Protestant policy.

Finally, a Dutch medal from 1686–7, which prompted a complex circulation of printed publications, showed the Waldensians together with the Huguenots not only at the moment of persecution, but also of the hoped-for redemption. Depicting both groups in the guise of ancient martyrs, the medal also prophesised their resurrection as the two witnesses of chapter eleven of the Revelation, in line with the contemporary predictions of Huguenot Pierre Jurieu from his chair in Rotterdam.

The Dutch reading public was therefore accustomed to the presence of the Waldensians in printed iconography, mainly in the bloody version of the persecutions. Following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes and in the context of the now harsh conflict between the Republic of the United Provinces and the Sun King’s France, the vicissitudes of the Waldensians were to take on a new role in the battle of images.

At the conclusion of the venture to return the Waldensians from exile – a decade later celebrated as a Glorieuse Rentrée – the Nieuwe Caerte der Valleyen published in 1691 is an effective synthesis of various aspects of the pro-Waldensian propaganda: the horror of persecution, the rescue, their role in the European geopolitical context of the conflict with France, and finally the depiction of the confessional identity of the area.

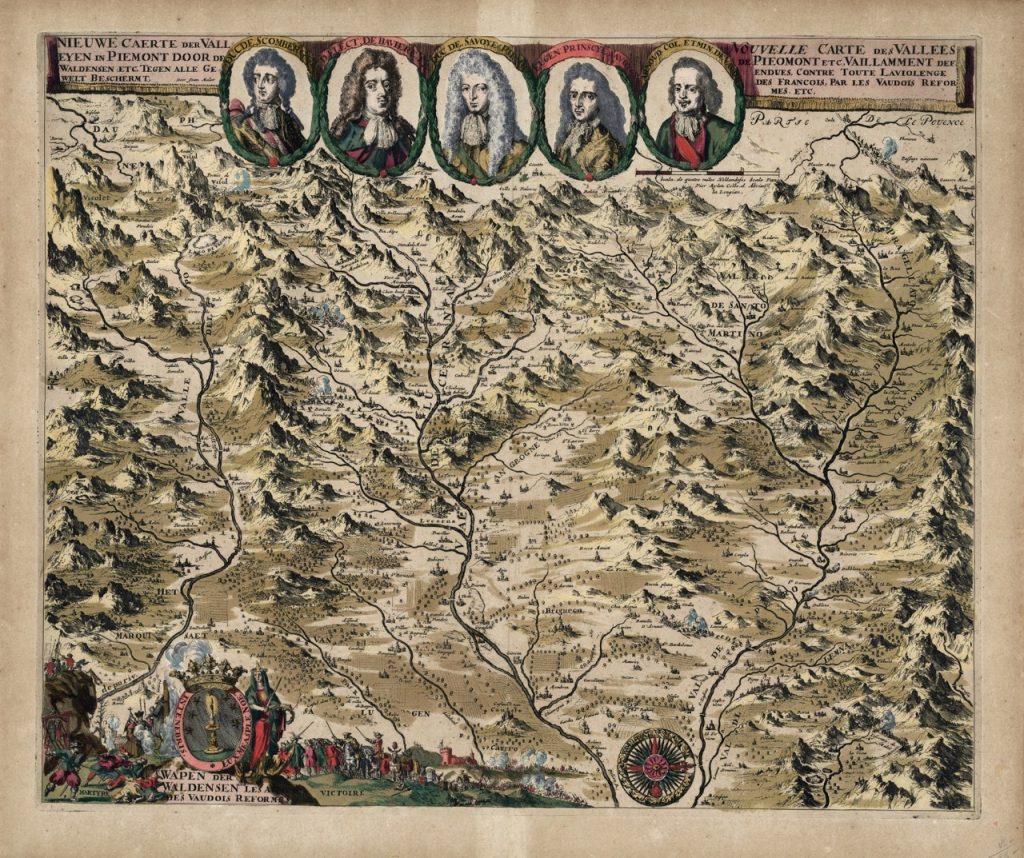

The description of the territory of those valleys – which within a few years the maps would begin to indicate as ‘Waldensian’ – contains not only references to natural and anthropic characteristics but also to the battles fought in the preceding years, which had seen the victory of the anti-French allies. The reference to the French responsibility for the exile of the Waldensians following the Edict of Fontainebleau is in fact made more explicit by the French title in the top right-hand corner: Nouvelle Carte des Vallees de Pieomont [sic], etc, Vaillamment defendues, contre Toute Laviolenge des Francois, Par les Vaudois Reformes, etc. Reinforcing this reading are the medallions in the upper band, depicting the leaders of the new anti-French alliance: Charles, Duke of Schomberg; Maximilian Emanuel II, Prince-Elector of Bavaria; Vittorio Amedeo II, Duke of Savoy; Prince Eugene of Savoy-Soissons; and Henri Arnaud, ‘col.[onel] et min.[istre] des Vaudois.’ (Fig. 2)

Figure 2: [Romeyn de Hooghe], Nieuwe Caerte der Valleyen in Piemont door de Waldensen, [1691], detail; from left to right: Charles, Duke of Schomberg; Maximilian Emanuel II, Prince-Elector of Bavaria; Vittorio Amedeo II, Duke of Savoy; Prince Eugene of Savoy-Soissons; and Henri Arnaud (Torre Pellice, Museo Valdese, property of Archivio della Tavola Valdese). © Courtesy Museo Valdese, Torre Pellice

The re-establishment of the Waldensians in their valleys following the intervention of the United Provinces and England created the conditions for a changed denominational geography in this part of Piedmont, governed by a Catholic sovereign. Made after the reconquest of the territory by the exiled Waldensians, the Nieuwe Caerte therefore contains a clear reference to contemporary events and personalities, reinforced by a symbolism that reaffirms the reconquest and the confessional belonging of those valleys.

The crowned Waldensian coat of arms stands out clearly on the lower left-hand side (‘T. Wapen der/ Waldensen’; ‘Les armes/ des Vaudois Reformes’), with the caption ‘Lux mea splenoet [sic!; i.e., splendet] in tenebris,’, accompanied by a female figure who can be identified as a symbol of the Church of Christ, depicted with a torch burning on her head, the crown of martyrdom, the Bible open in her left hand and a sword raised in her right, while with her feet she tramples a dragon with diabolical features. (Fig. 3)

Figure 3: [Romeyn de Hooghe], Nieuwe Caerte der Valleyen in Piemont door de Waldensen, [1691], detail of the Waldensian coat of arms and war scenes (Torre Pellice, Museo Valdese, property of Archivio della Tavola Valdese). © Courtesy Museo Valdese, Torre Pellice

On either side are two scenes of opposing outcomes for the Waldensians: on the left, defenceless civilians are thrown from a cliff, hanged, pierced by soldiers with swords and spears, impaled on a tree trunk, burnt at the stake with the complicity of Catholic missionaries, while a village is set on fire in the background. The inscription ‘Martyre’ provides a comment to these scenes. On the opposite side, a little further to the right over the inscription ‘Victoire,’ a long line of soldiers, including some on horseback, escort a group of prisoners wearing bulky, showy wigs, accompanied by mules probably carrying booty, while at the rear of the column men on foot, armed with long spears, repel the attack of other infantrymen and horsemen. The two extremes of the events experienced by the Waldensians in the space of a few years are thus linked by clearly symbolising the revenge and reconquest of the valleys, culminating in the re-establishment of the reformed faith.

The two opposing images thus portray a situation that changed within just a few years, up to the reintroduction of the reformed faith in the Piedmont valleys, which was also seen abroad as a victorious event, especially for the French Huguenots exiled in the Low Countries

Everything in this depiction of the Waldensian valleys shows the propagandist intent to magnify the exploits of the Protestant powers and the defeat of France: the severe portraits in the medallions, the battle scenes in the lower part, the Waldensian coat of arms and the frontal view of the valleys make it a clear political manifesto.

Until now it has not been possible to clarify whether the Nieuwe Caerte was produced for publication in a printed volume or for independent circulation. Later, from the 1720s onwards, it was included in atlases compiled with maps by various cartographers from different periods. Ottens’s sons included it (at no. 48) in the Catalogue Nouveau des Cartes Géographiques, which they printed and sold in Amsterdam between 1737 and 1750; it was then also included in the Atlas Nouveau contenant toutes les parties du monde by Johannes Covens I and Cornelis Mortier, which circulated throughout the second half of the century.

Marco Fratini is art historian and librarian at the Waldensian Cultural Center Foundation (Torre Pellice, Italy). His studies focus on Waldensian history, the history of Piedmontese art and historical cartography.

Bibliography

de Lange, A. (ed.). Dall’Europa alle Valli valdesi. Proceedings of the XXIX international conference on history ‘Il Glorioso Rimpatrio (1686–1989. Contesto – significato – immagine.’ Torre Pellice, 3-7 September 1989. Turin, 1990.

Fratini, Marco. ‘Una frontiera confessionale. La territorializzazione delle Valli valdesi del Piemonte nella cartografia del Seicento.’ In Confini e frontiere: un confronto fra discipline, edited by Alessandro Pastore. Milan, 2007, 127–43.

Fratini, Marco. ‘Waldenzen Predikanten. Pastori valdesi alla fine del Seicento, in due incisioni di Romeyn de Hooghe.’ Riforma e Movimenti Religiosi 10 (2021): 59–88.

Fratini, Marco. ‘Les Vaudois dans la propagande visuelle des Provinces-Unies à la fin du XVIIe siècle.’ Revue d’Histoire du Protestantisme 4 (2021): 401–40.

Tarantino, Giovanni. ‘Mapping Religion (and Emotions) in the Protestant Valleys of Piedmont.’ ASDIWAL. Revue genevoise d’anthropologie et d’histoire des religions 9 (2014): 91–105.

Tron, Daniele. ‘La definizione territoriale delle Valli valdesi dall’adesione alla Riforma alla Rivoluzione francese.’ Bollettino della Società di Studi Valdesi 189 (2001): 5–26.