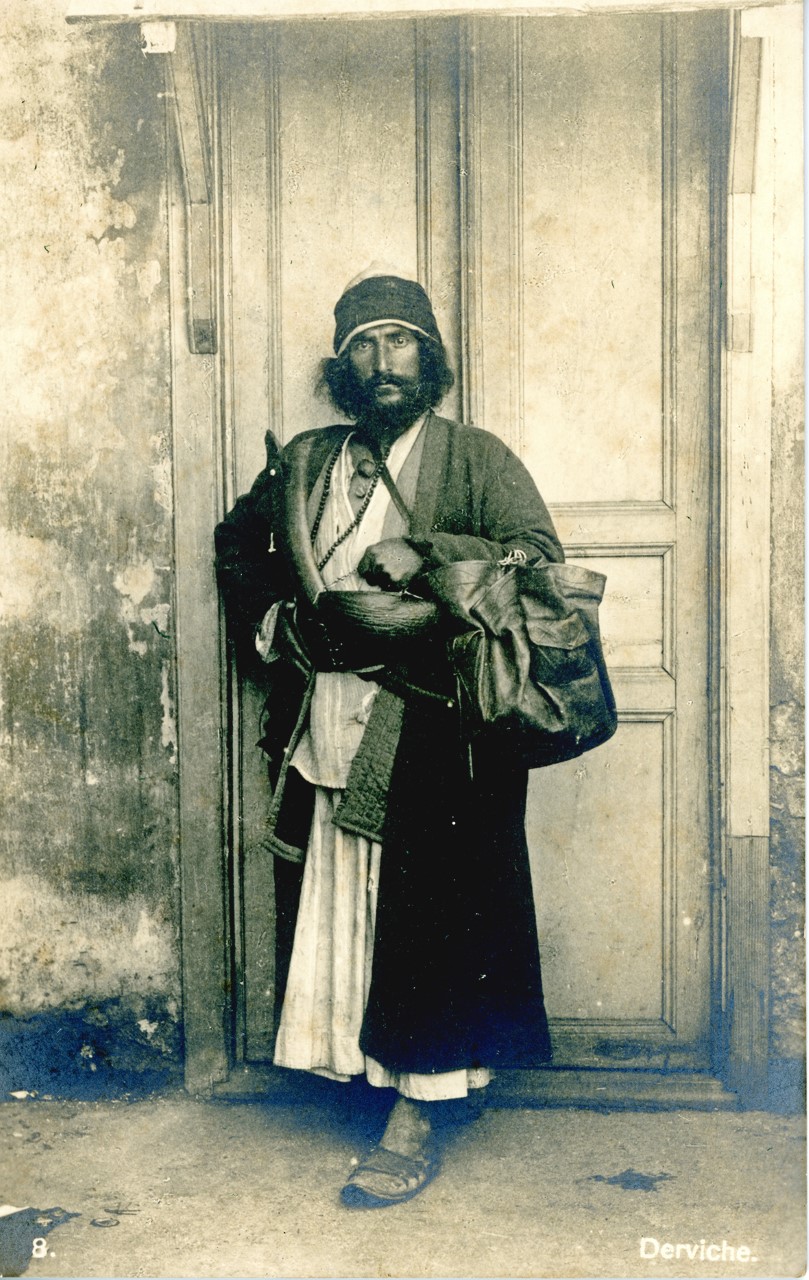

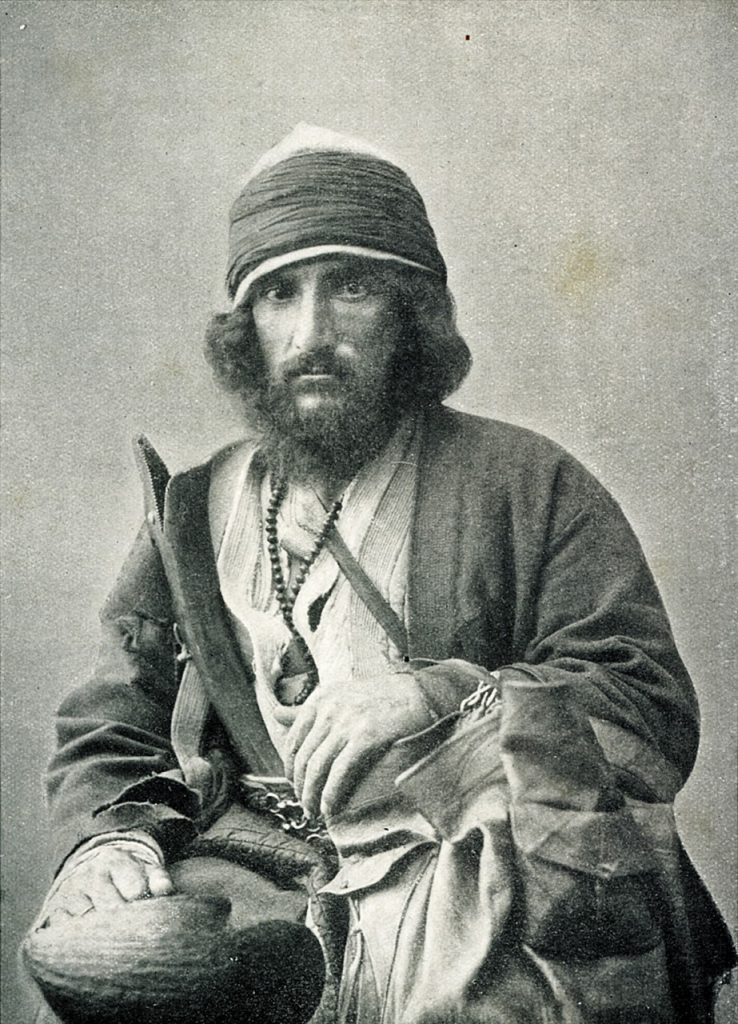

A man stands in front of a door and looks the observer directly and intensely in the eyes. Under a tight-fitting cap, long dark hair and a beard can be seen framing his serious-looking face. He wears several layers of clothing under a dark coat, jewellery around his neck and several implements typical of his profession or, in other words, of the image he is supposed to give: a large leather bag, a vessel made of half a sea coconut from the Seychelles or coco-de-mer with a carrying chain, a curved signalling horn whose tip with its eye represents the face of a fish with its mouth wide open.

A postcard from Istanbul from the early 20th century shows this motif (Fig. 1). Its content is explained and categorised as briefly as possible by a legend in French in the bottom right-hand corner: “Derviche”. At the bottom left, the number 8 indicates that this image is part of a series of pictures. The reverse of this card does not reveal much more: apart from lines to mark the demarcation between the correspondence and address sections and some address lines, a manufacturer’s signet with the three letters N, B and C in a triangular frame at the top right in the stamp box refers to the Berlin picture printing price cartel “Neue Bromsilber Convention”, which was active from 1909 until around 1930.

Figure 1: Postcard from Constantinople, first quarter of the 20th century. Private Collection.

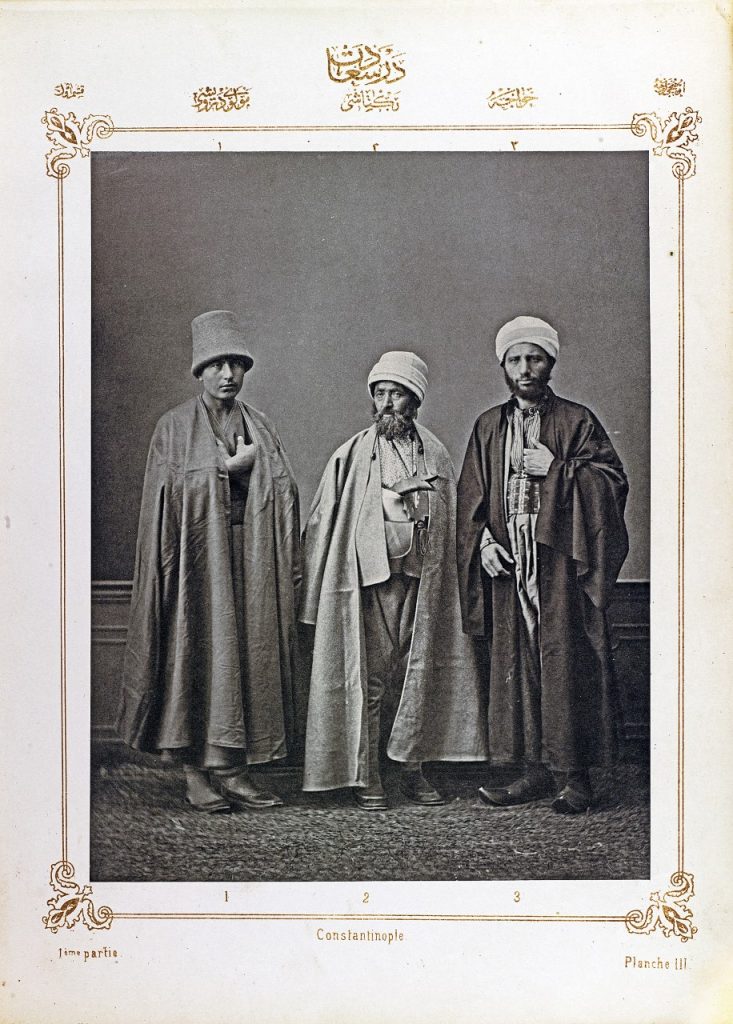

The photograph on this postcard is well-composed and conveys a view that goes back to a long tradition of reports and images and should thus fully meet the expectations of the tourists for whom such cards were produced. As in earlier times, travellers and visitors to the capital of the Ottoman Empire, well prepared by reading travelogues, could expect to encounter various groups of religious specialists in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. An image by the photographer Pascal Sébah (1823–1886), which found its way into the representative work Les costumes populaires de la Turquie en 1873 by Osman Hamdi Bey (1842–1910), makes clear, much simplified, what these groups of religious persons were.

Plate III of Part 1 of this richly illuminated work, which was illustrated in the modern medium of photography but in a rather traditional manner of staging people, produced to represent Turkey at the Vienna World’s Fair, shows a dervish of the Mevlevi Order, a member of the Bektashi Brotherhood and a mullah or hodja as a representative of official Islam, each in appropriate dress. (Fig. 2)

Figure 2: “Mevlevi Dervish, Bektashi, Hodja”. Print after a photograph by Pascal Sébah, in Osman Hamdi Bey, Les costumes populaires de la Turquie en 1873. Public Library Boston. Public Domain.

The depiction of typical groups of people against a neutral background goes back to long-established practices of display. In woodcuts and copper engravings of the widespread works of, for example, Nicolas de Nicolay (1517–1583), Salomon Schweigger (1551–1622), Paul Rycaut (1629–1700) and Ignatius Mouradgea d’Ohsson (1740–1807), a common way of depicting people in their costume became established; the early photographs that show an oriental population not only adopted the categorisation into representative groups of people from such previous works, but also the style of portraying people in their typical costume and with the attributes that made them recognisable and assignable.

The figure of the Bektashi brother is depicted in Sébah’s photograph with similar attributes to the person on the postcard mentioned above: bearded, carrying a bag and a characteristic bugle. In contrast to the Mevlevi Sufis, who gained notoriety as “Whirling Dervishes”, the Bektashi were often simplified as belonging to the “Howling Dervishes” along with other religious orders. As was known from many travel reports, the weekly evening events in the monasteries of both dervish categories could be attended by people from outside the order as well as by foreigners. The fascinating whirling dances of the Mevlevi as well as the trance ceremonies of the so-called howling dervishes, who loudly recited the Islamic creed or abbreviations of it, did not fail to make a powerful impression on the spectators. Visiting a monastery had been a common tourist attraction since the 17th century; accordingly, there was a great demand for suitable visual material to be taken home.

The dervish depicted on the postcard proves to be a member of a mendicant order. Both the beggar’s pouch and the bowl made of half a coco-de-mer are used to receive charitable gifts. The bugle serves to announce his coming. The fact that this man is depicted in front of a door is a learned reference to the etymology of the term “dervish”, which, as derived from a composite of the word “dar” (Persian: “door”) and “wish” (from “wihtan” for “begging”), denotes persons who go from door to door and earn their living by begging. However, begging was not primarily based on compassion or charity, but represented a special form of religious interaction in which giving and receiving were in balance. The dervish imparted religious blessings, be it through his mere appearance as a person very close to the divine, be it through intercessions and advice or even through the intentional exploitation of the saintly status of a person who moved outside all convention and was therefore endowed with special powers. In return, he received worldly gifts that made his life as a man of God possible at all.

What is very remarkable about this photographic record is that the penetrating gaze of the dervish conveys a narrative and pictorial tradition that, with a certain ambivalence, has repeatedly been found worthy of mention in words or captured in photographs. Already the Hungarian lay brother Georgius (ca. 1422–1502), who published his experiences of his captivity in the Ottoman Empire in Rome in the late 15th century and is the first Western author to list the word “dervish” and to explain the Islamic orders encountered at that time in all their diversity and in all the shades of their manifestations, said of the appearance of these religious figures in the Tractatus de moribus, condictionibus et nequicia Turcorum (sheet 18rf., my translation): “Often, however, those who were our guests offered consolation to the audience with the sermons mentioned above. They are of such exemplary character in all their words and works and also display such piety in behaviour and appearance that they do not seem to be men but angels. For such spirituality is expressed in their traits that you could recognise any one of them immediately if you only looked him in the face – even if you had never seen him before.”

Ever since Georgius de Hungaria it was often never quite clear to the mostly suspicious observers what was authentic about the rather strange-seeming religious practices and behaviour of the monks and what was merely pretended or faked, and therefore, whether the religious motivation could be trusted. There was indeed a wide range of inner and external reasons that led men to walk through life in the garb of a wandering dervish. Dressing up in a religious outfit and thus assuming a clearly visible social position was sometimes a welcome way out of a perplexing life situation, which made it possible to feel a sense of belonging or to make a living. It is difficult to clearly separate from within such a way of life the people with true spiritual gifts and a deeply mystical orientation. In any case, taking on a role served the purpose of integration into a social group.

Created by the British James Justinian Morier (1782–1849), the figure of the Persian Hajji Baba, whose adventures the author initially published anonymously in 1824 and whose life story, omitting no cliché, leads through all realms of oriental life, also lives for a time among dervishes, who tell him their life stories and encourage him to equip himself as a dervish with the appropriate requisites. Morier paints a picture of wandering dervishes that mocks their hypocritical practices, but which, as the enthusiastic reception of Hajji Baba’s account in Persia at the time showed, was also perceived and widely shared by many locals themselves in just the same way. For the dervishes, in order to equip themselves in accordance with their status, there seem to have been specialised shops for dervish needs in the Orient. This is what the traveller Isabella L. Bishop Bird (1831–1904) wrote in her Journeys in Persia and Kurdistan of 1891 (vol. I., p. 238): “… a dervish at the door is still a sign of being great or rich, or both. Their cries, and their rude blasts on the buffalo horn, which is a usual part of their equipment, are most obnoxious. In the larger towns, such as Kûm and Kirmanshah, there are shops for the sale of their outfit – the tiger and panther skins, the axes, the knotted clubs, the alms bowls, etc.”

Equipment appropriate to the subject being portrayed is also visible in the studio photographs. Whether the people photographed in the studios were people taken off the street in their own garb or were just outfitted according to their role cannot be easily determined. There exists another photograph of the man depicted on the postcard under discussion, which William B. Seabrook (1884–1945), a most unorthodox American writer, published in his Adventures in Arabia. Among the Bedouins, Druses, Whirling Dervishes, & Yezidee Devil Worshipers without further reference. (Fig. 3)

Figure 3: Illustration in William B. Seabrook, Adventures in Arabia, on the right of p.284. Private Collection.

Here the dervish, the same person as on the postcard, dressed in his paraphernalia, is shown in a sitting position, and here, too, his special gaze is striking. In the caption, this person is described as follows: “A sheik of the Rufai or Howling Dervishes, who slash themselves with knives” – an intriguing attribution, which in turn refers to another pictorial tradition not discussed here, but very old: that of the self-harming dervishes.

Focusing on visual considerations, it can be concluded that pictoriality is an important, probably indispensable component of social group formation, which on the one hand is fixed, but on the other hand can also be managed flexibly. Visuality confronts us in two ways: As an image that people give of themselves (and which they can also actively take on, depending on the situation), and as an image that spreads as a product. Groups differ from each other in their costume, their appearance. The adoption of a social identity happens by dressing accordingly, by appearing as a bearer of a specific image. On another level, such images are reproduced and thus become what we understand by images in the narrower sense: Drawings, images reproduced in print and photographs. The spread of these images, in turn, perpetuates and reinforces the fixedness of socially cultivated images.

For the social image to function, i.e. to take on its social task, it must be as unambiguous and typical as possible. It relies on being understood. The reproduced, flat images have the same effect. Especially, if they are made for tourists, they build on the familiar, they simplify and reinforce typologies. Similar to the image of the “dervish” as a begging subject who travels through the world with the greatest possible disdain for mundane circumstances and carrying heavenly blessings with him, the image of him on the postcard or in books travels away from the place of origin and the real circumstances and, in a grand transformation into image ciphers, reaches the fascinated recipients, whereby, if people presenting themselves as dervishes fit the image, they may well regain social relevance and earnings.

Andreas Isler is Curator at the Ethnographic Museum of the University of Zurich with responsibility for the Department of the Orient and Southeast Asia.

Bibliography

Bishop Bird, Isabella L., Journeys in Persia and Kurdistan. John Murray: London 1891.

Georgius de Hungaria, Tractatus de moribus, condictionibus et nequicia Turcorum. Georg Herolt: Rome [ca. 1481].

Hamdi Bey, Osman, Les costumes populaires de la Turquie en 1873. Levante Times & Shipping Gazette: Constantinople 1873.

Isler, Andreas, and von Wyss-Giacosa, Paola, Gemachte Bilder – Derwische als Orient-Chiffre und Faszinosum. Ethnographic Museum of the University of Zurich: Zurich 2017.

Isler, Andreas, Alles Derwische? Anschauungen, Begriffe, Bilder. Zur Darstellung von islamischen Ordensleuten in westlichen Orientwerken der frühen Neuzeit. Ethnographic Museum of the University of Zurich: Zurich 2019.

Klockow, Reinhard (Hrsg.), Georgius de Hungaria. Tractatus de moribus, condictionibus et nequicia Turcorum. Traktat über die Sitten, die Lebensverhältnisse und die Arglist der Türken. Nach der Erstausgabe von 1481 herausgegeben, übersetzt und eingeleitet. Böhlau: Köln, Weimar, Wien 1993.

Morier, James Justinian, The Adventures of Hajji Baba of Ispahan. John Murray: London 1824.

de Nicolay, Nicolas, Les Quatre Premiers Livres des Navigations et Pérégrinations Orientales. Guillaume Rouille: Lyon 1567.

d’Ohsson, Ignatius Mouradgea, Tableau général de l’Empire Othoman. L’imprimerie de Monsieur: Paris 1790.

Rycaut, Paul, The Present State of the Ottoman Empire. John Starkey and Henry Brome: London 1667.

Schweigger, Salomon, Ein newe Reyßbeschreibung auß Teutschland Nach Constantinopel vnd Jerusalem… Mit hundert schönen newen Figuren. Johann Lantzenberger: Nuremberg 1608.

Seabrook, William B., Adventures in Arabia. Among the Bedouins, Druses, Whirling Dervishes, & Yezidee Devil Worshipers. Harcourt, Brace and Company: New York 1927.