In the first half of the seventeenth century, Albania was already an Ottoman outpost. Indeed, it is very well known that the early modern Balkan peninsula, if we exclude the Dalmatian area, belonged to the sultans: Albania, in particular, despite the opposition organised by Skanderbeg, had been subjugated by the so-called ‘Turks’ in the last decades of the fifteenth century. Scutari (present-day Shkodër, in Albania) and Durazzo (present-day Durrës, Albania), formerly belonging to Venice, now lay under the flag of the Sublime Porte.

As it is commonly recognised, the Ottoman Empire was a multi-ethnic and multi-confessional entity, and Albania was no exception. The pre-Ottoman religious landscape was characterised by the substantial presence of Catholic groups in the northern part of the region, while in the south the orthodoxies represented the overriding majority among the Christian communities.

In fact, the Ottoman conquest did not result in mass conversions throughout the Balkan area: a significant number of conversions only occurred in a few, specific regions of the Balkans, as was the case with Bosnia and Albania. As early as the seventeenth century, the Islamisation process began increasing among the Albanians, slowly yet irreversibly: most conversions took place in the Catholic north, while, at a first stage, the south remained substantially Orthodox.

How did the Roman Catholic church react towards this worrying confessional haemorrhage? The papacy still had a glorious, thinly disguised dream of defeating the Ottomans and expelling them from the Mediterranean basin: the idea of crusades was still considered to be a proper and lawful response to the Ottoman threat, and the memory of the unexpected military success over the Ottoman army in Lepanto (1571) was somehow still alive.

On the other hand, the European kingdoms and states tended to be more cautious on the matter: they often switched from opportunistic, diplomatic alliances with the sultan (in this regard, we could mention the well-known network of alliances between the kingdom of France and the Sublime Porte, consolidated as early as the sixteenth century) to moments of collision and open conflict. Apart from the ineffective military approach, however, the Holy See progressively implemented a missionary project, especially after the foundation of the Propaganda Fide (1622), the ministry responsible for missionary activities all over the world. The purpose was clear: the papacy was keen to prevent conversions to Islam as well as forms of religious syncretism, and in this sense intended to use its missionaries, who became local agents of the Holy See.

The missionaries put a lot of effort into portraying the local Catholic minority and environment they were living in: the reports sent to the Congregazione de Propaganda Fide provided vivid descriptions of the territories the missionaries visited, the social customs they encountered, not to mention the local clergy and Catholic hierarchies they were working with. Due to the wealth and accuracy of this information, these documents are often an exceptional source of data to study the customs and social conditions of the people they visited: recording and describing were paramount duties, as the papacy, Propaganda and local Catholic hierarchies needed greater knowledge of the area in order to improve their pastoral work.

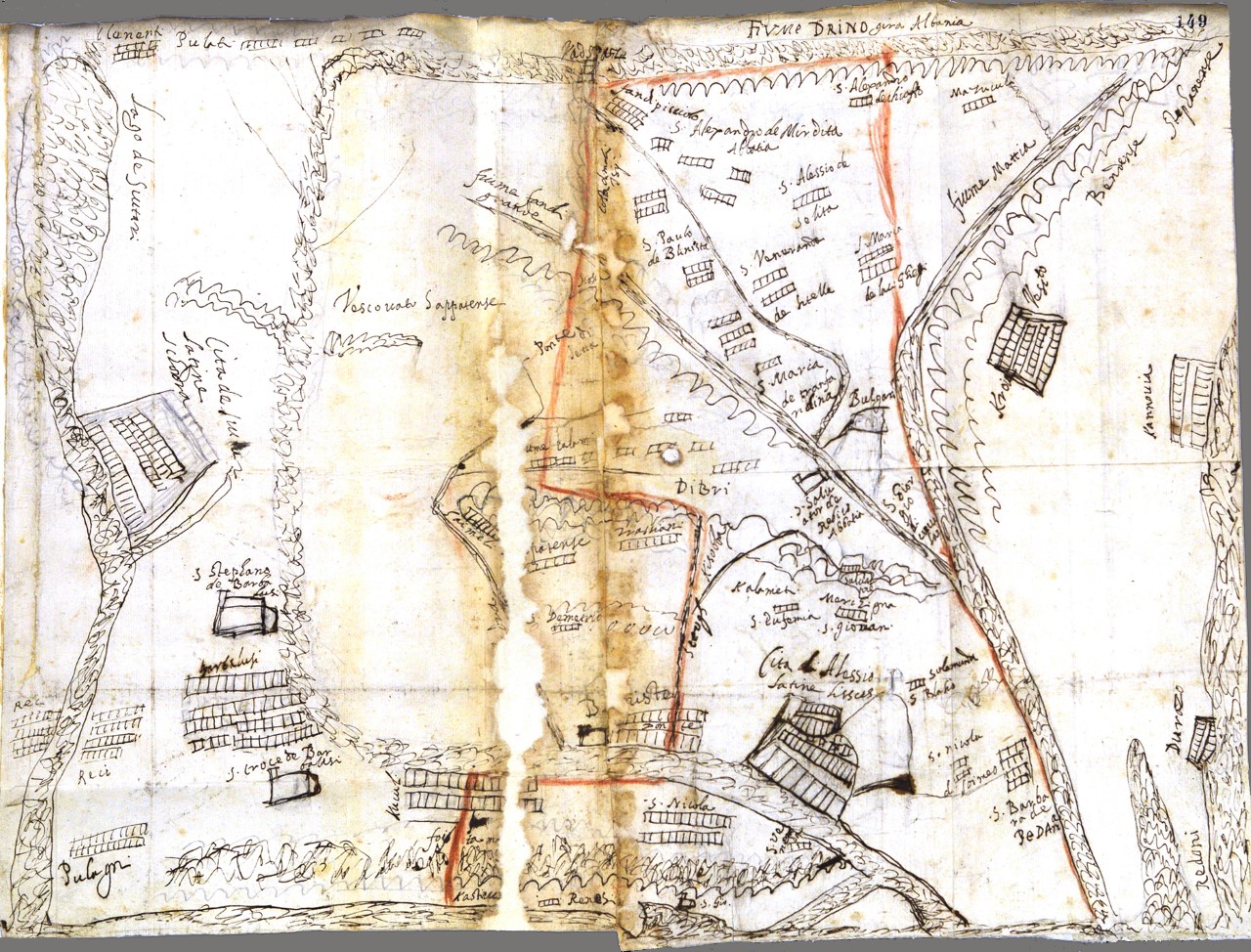

For instance, the handmade map on display here gives a visual outcome of these needs. It is an independent document included in a rich folder pertaining to Servia Albania Dalmatia Illyricum ab an. 1630 ad 1639 (APF, SOCG. 263, f. 149r.). (Fig. 1)

Figure 1: Catholic bishoprics in Northern Albania (first half of the 17th century), Archivio Storico di Propaganda Fide, Città del Vaticano, APF, SOCG. 263, f. 149r. © Archivio Storico di Propaganda Fide.

The map, primarily serving as an internal administrative tool, shows the territory between Shkodër and Durrës, where several Catholic communities were displaced. As we can see, the lake of Shkodër represented the border dividing northern Albania and southern Dalmatia; while the River Drin separates the ecclesiastical province of Albania from that of ‘Servia’.

More precisely, the map also sheds light on the boundaries dividing the Albanian bishoprics. Nevertheless, interestingly enough, it does not encompass Antivari (nowadays Bar, in Montenegro), which, at that time, was also included within the ecclesiastical province of Albania.

Indeed, on the right bank of the River Drin, there is the ‘Vescovado Sappatense’ (Sappatensis bishopric), while the River Mattia (today Mati) naturally defines the border of the ‘Bendensis and Stephanensis’ bishopric. The diocese of Alessio (Lezhë), for its part, is very clearly delimited by a thick red line. Evidently, the author devoted peculiar attention to the territory included within the Alessiensis bishopric.

It is clear that he has carefully sketched the villages and parishes of that area, even the smallest ones (for instance, ‘San Nicola [saint Nicholas] de Soimeo’ (Zojmeni) and S. Barbara [saint Barbara] de Pedana’ (Pëdhana) located in the vicinity of Alessio). On the contrary, the author only reports a few of the parishes pertaining to the other dioceses, such as Shkodër, Durrës and Kruja, the main cities of the area, ‘Clementi’ and ‘Pulati’ (upper left corner) or ‘Barbalussi’ (a parish on the left side of our map, close to the River Drin). Why does he do this?

As it has been demonstrated, jurisdictional quarrels over parishes, bishoprics and chapels were not at all uncommon in the early modern Ottoman Balkans, and, once again, Albania was no exception. Local bishops entered arguments in order to extend the boundaries of their territory, as proven – incidentally – by a wide variety of the documents included in the same folder. For instance, plenty of letters prove the existence of a lengthy, severe dispute over ‘Santo Stefano de Barbalussi’, aggressively contended between Gjergj Bardhi, archbishop of Antivari and Benedetto Orsini, bishop of Alessio and Scutari, between the 1620s and the 1630s.

Realistically speaking, the map we are focusing on should be seen in the light of this historical and jurisdictional background. To whom did a certain parish belong? Who was responsible for it? Who was supposed to collect tithes (decime) from a certain village? These questions were paramount in Ottoman-occupied Albania, where churches, priests as well as economic resources were incredibly scarce.

More often than not, Catholic communities were financially strapped and could not afford to build new churches or repair ones that had fallen into bad shape. Thus, they could barely celebrate holy mass. In addition to the lack of places of worship, local clergy could also represent a major problem for Albanian Catholicism: as a matter of fact, there was a serious shortage of well-educated priests whose expenses could be met and it is not rare to find reports of the missionaries’ frustration at the local priests’ ignorance, inability to speak Latin and corruption. The harsh conditions faced by the Albanian Catholics – both spiritually and socially – could easily pave the way for conversion to Islam, the missionaries claimed.

That is why the Propaganda and its local agents needed to take a census of the Catholic minority for the geolocation – as we would say nowadays – of the people and venues representing the bedrock of their work. Indeed, it was essential in order to distribute further missionaries and subsidies, but more importantly to get acquainted with the local environment – politically, socially and, of course, confessionally.

The overriding majority of conversions to Islam, in northern Albania, occurred among people who lived in urban environments, such as Shkodër and Lezhë, while those who inhabited the mountains tended to preserve their previous religious identity. As a matter of fact, the Ottoman army struggled to subjugate these communities, as the barren and rugged territory proved challenging and hard to control.

It comes as no surprise then that missionaries tried to pay particular attention to the Catholics living in the mountains. The Kelmendi tribe (Clementi in the picture), for instance, was considered to be a real outpost in this regard: the missionaries often described them as proper Catholic people (and in fact only a small number of them converted to Islam) and well-trained warriors who could give the Ottomans a hard time.

However, the reality of the matter was slightly different. Even those who identified themselves as Catholic showed peculiar religious identities, enmeshed with social customs as well as other confessions. Overall, they were living under the rule of an Islamic empire and Catholic confessionalisation, as developed in Western European countries, was far from being fulfilled.

References

P. Bartl, Albania Sacra. Geistliche Visitationsberichte aus Albanien. Voll. 4. Wiesbaden 2007-2017.

F. Cordignano. “Geografia ecclesiastica dell’Albania dagli ultimi decenni del secolo XVI alla meta del secolo XVII”. Orientalia Christiana 36. Pont. Institutum Orientalium Studiorum. Roma 1934.

N. Malcolm. Rebels, Believers, Survivors. Studies in the History of the Albanians. Oxford 2020.

N. Malcolm. Useful Enemies. Islam and The Ottoman Empire in Western Political Thought, 1450-1750. Oxford 2019.

A. Molnár. Confessionalization on the Frontier. The Balkan Catholics between Roman Reform and Ottoman Reality. Roma 2019.

I. Zamputi. Dokumente për historinë e Shqipërisë (1623-1653). St. Gallen- Prishtinë 2015.