Exploring how the flows and counterflows of artefacts and materials shaped broader trans-Mediterranean affective spaces of shared interests and experiences, this brief contribution to ‘PIMo visual reflections’ is an appetiser for the forthcoming volume The Habsburg Mediterranean, 1500–1800, edited by myself and Dorothea McEwan. Thanks to the generous support of the COST Action PIMo People in Motion: Entangled Histories of Displacement across the Mediterranean (1492–1923), this volume will be published with the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna, in 2021.

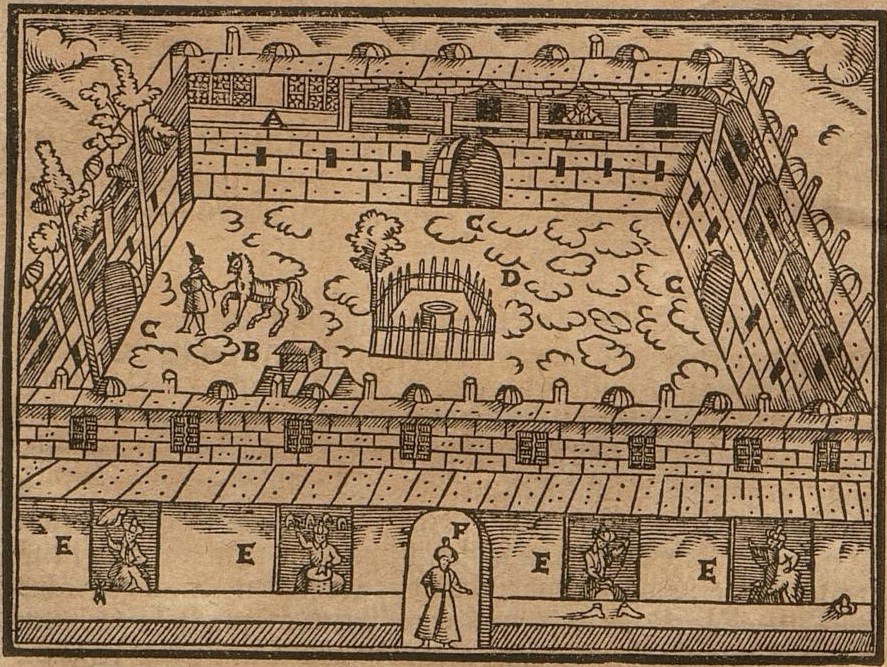

In my own chapter contribution to this volume, I take the imperial embassy (elçi han) in Istanbul as a starting point for a reconsideration of the cross-cultural dynamics of material exchanges. The Habsburg compound in Istanbul was a lively venue for fostering cultural contacts and exchange across the religious and imperial divide. Sixteenth-century chaplains to the imperial embassy portrayed the residence as a large building complex guarded by Ottoman personnel, five çavuşes and four janissaries (Fig. 1). The embassy building itself was constructed like caravanserais around an inner courtyard that accommodated a number of chambers, kitchens and stables with space for more than 400 horses. The balustrade of the second floor gave access to the large dining and residence hall and offered a view of the courtyard and all the comings and goings down below there. The windows of the residents’ rooms could be opened to the streets as well as to the building’s inner courtyard. Little stores run by craftsmen and artisans like dressmakers, shoemakers and blacksmiths further connected the inner part of the building with the busy streets of Istanbul.

Such sixteenth-century descriptions and visual representations, thus, illustrate that the residence cannot be considered a space of isolation and enclosure, but of contacts as well as of social and religious diversity. The imperial embassy was a lively space that stimulated contacts between Habsburg and Ottoman subjects, as well as between Christians, Jews and Muslims on the one hand and between noblemen and craftsmen on the other; contacts that made the imperial embassy a hub for the exchange of objects and a prime agent in the moulding of shared aesthetic styles and tastes. The imperial embassy in Istanbul, I argue in my book chapter, was a microcosm in which the Habsburg Mediterranean materialised. The embassy’s material dynamism connected the Holy Roman Empire with the material culture of the Ottoman Empire and the broader Mediterranean world.

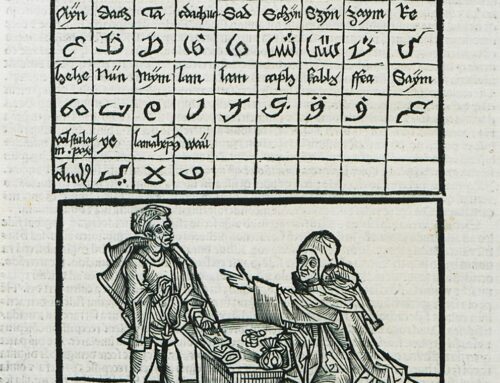

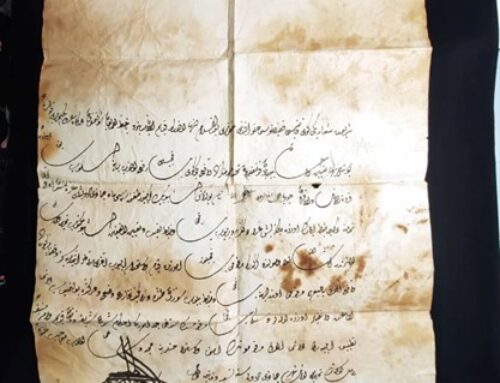

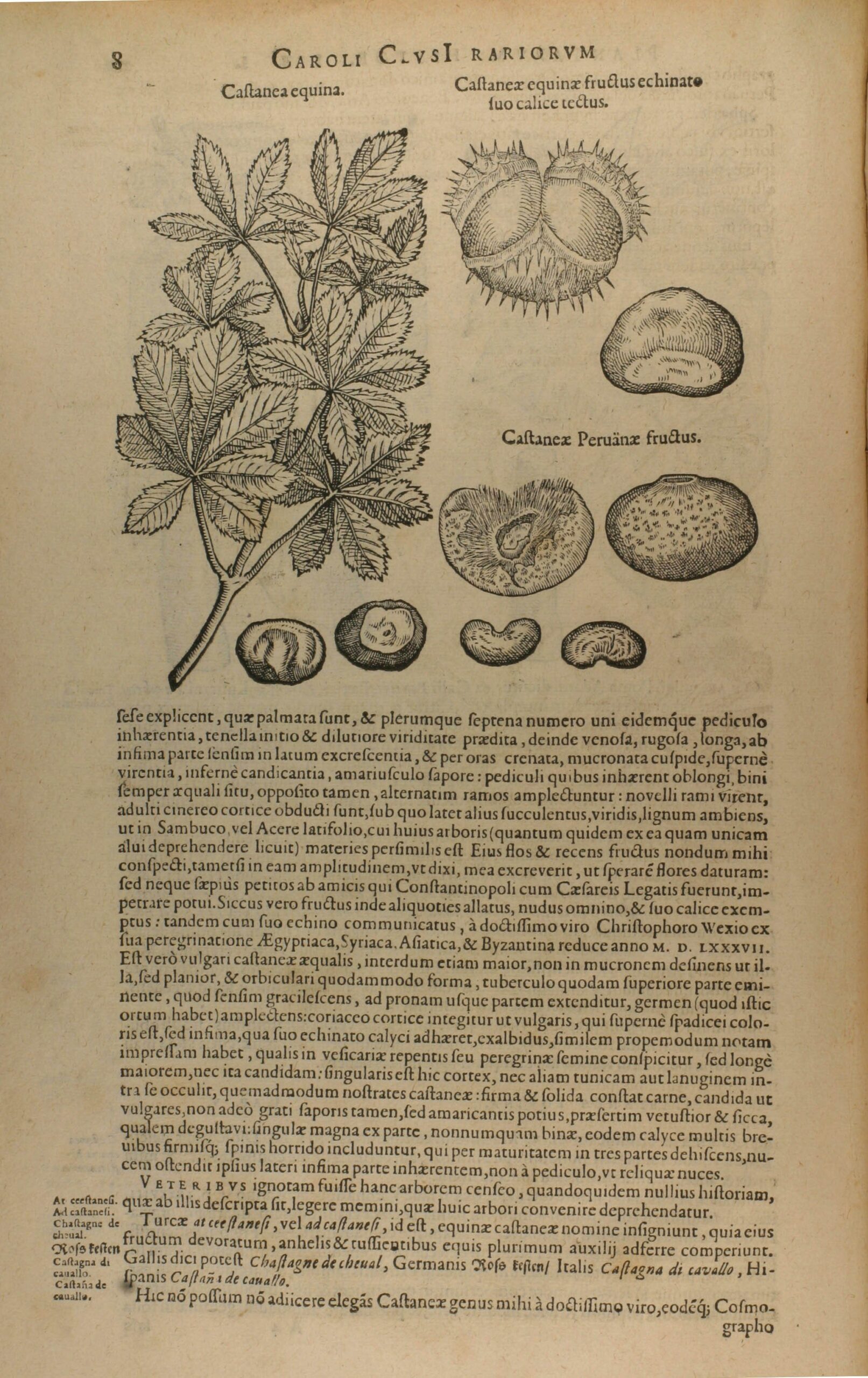

The particular location and spatial arrangement of the embassy fostered contacts across the religious divide and attuned the Habsburg ambassadorial entourage to engage with the broader material world of the Ottoman city. Many residents at the Habsburg embassy experienced Istanbul on a very material level. In my book chapter, I trace the complex history of a variety of sixteenth-century residents that purchased, produced and perceived objects that made up their knowledge about the city. For buying “many beautiful materials and things”, one resident states in his diary, he got in contact with “Arabs, Jews and Turks” living in Istanbul. He was no exception. A variety of the embassy’s residents made a collection of various items whilst in Istanbul. They purchased or collected sketches of Ottoman antiquities, Ottoman language materials and manuscripts, antiquities, remedies, clothing, shoes, weapons, and even horse chestnuts (fig. 2), which were sent back to the Habsburg heartlands in Central Europe. Here, they got marvelled and inspired further engagement with the Ottoman material world.

Fig. 2: Illustration and description of a horse chestnut sent to Vienna by the imperial ambassador in Istanbul. ©Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München, 2 Med 54#(Beibd.), S. 8, urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb11199942-9.

Such illustrations and descriptions document the general appreciation of Ottoman material culture by those living in the Habsburg imperial embassy’s residence on the one hand. On the other, they invite further reflection on the role of early modern material culture to establish, channel, and maintain broader affective trans-Mediterranean communities across assumed religious divides. I would be delighted if readers might take this blog entry as an invitation to read more about such fascinating stories in my forthcoming book chapter.

Stefan Hanß is Senior Lecturer at the University of Manchester. His research focuses on material culture and cultural encounters in the early modern world. Hanß was awarded a British Academy Rising Star Engagement Award and a Philip Leverhulme Prize in History. He has published widely on the Battle of Lepanto, Mediterranean slavery, Ottoman language-learning in the early modern period, as well as concepts of time. This PIMo visual reflection post is based on Stefan Hanß, ‘A Shared Taste? Material Culture and Intellectual Curiosity in the Habsburg Mediterranean’, in The Habsburg Mediterranean, 1500–1800, edited by Stefan Hanß and Dorothea McEwan (Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences, 2021, in press). His current research examines the history of early modern feather-working and hair.