The aim of this brief document is to draw attention not only to totemic, highly symbolic objects and curiosa as three-dimensional evidence, but also to value hoaxes, forgeries and copies, which can be as interesting for researchers as the originals themselves, since, as Schlebecker (1977) pointed out, a replica can sometimes effectively substitute the “real thing”.

Starting from Omar Al Mukthar’s glasses (with which he was typically portrayed), stored in the warehouse housing the former Museo Coloniale of Rome, I will consider their “appearances” (in museums and shops) and evocations (on paper, in movies) in different contexts and scenarios, as they multiply like a modern-day relic. This short piece will also contribute to highlighting the extent to which the flow of (real or presumed) objects across the Mediterranean is deeply entangled in empire-building, nationalist reactions and postcolonial contestations.

Omar Al-Mukhtar (18581931) is known as the martyr who sacrificed his life while trying to free Libya from Italian colonialism. On 3 October 1911, as the Italians bombarded Tripoli in the first act of what was to be known as the Italo-Turkish War, the Ottoman military command decided to retreat, and launched resistance from the hinterland. Mukhtar repeatedly led his small groups in successful attacks, after which they would fade back into the desert terrain, skilfully attacking outposts, ambushing troops, and cutting lines of supply and communication. The Italian control over much of the Libyan interior remained ineffective until the late 1920s, when forces under Generals Pietro Badoglio and Rodolfo Graziani responded with ever-growing levels of brutality to eliminate support for the rebels. Mukhtar’s struggle of nearly twenty years came to an end on 16 September 1931, when he was hanged before his followers in the camp of Suluq, at the age of 73.

Immediately afterwards, the personal belongings, notably his leather wallet and eyeglasses, of the Senussian leader were sent to the Museo Coloniale of Rome, testifying that, finally, the complete conquest and pacification of Libya had taken place. The glasses and the wallet, rather banal everyday objects, of the man once symbol of the Libyan resistance were to be exhibited as “trophies”.

After his death, Omar Al-Mukhtar became a transnational icon and a Pan-Islamic banner, not only in the Arab world, but in Indonesia too, where the Dutch colonial government was quite aware of the issue’s sensitivity, and forbade newspapers from even mentioning Al-Mukhtar. The death of the Libyan leader gave impulse to an anti-Italian movement in the Muslim world; Italian products were also boycotted in many countries, and throughout the past century streets were named after the Libyan resistance leader in Kuwait, Gaza, Egypt, Doha, Tunisia, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Morocco, etc.

As Gaddafi and the Revolutionary Command Council (RCC) rose to power in 1969 and claimed his legacy, al-Mukhtar’s name and image suddenly became ubiquitous in Libya. Roads were named after him, his image (with the famous glasses) appeared on Libyan currency and the government financed a 1981 movie, “Lion of the Desert”, in which Al-Mukhtar was played by Anthony Quinn. While the film was shown regularly on Libyan state television, it was banned in Italy until its first broadcast on Italian TV in 2009.

In summer 2009 Muammar Gaddafi met President Silvio Berlusconi in Rome. Pinned to Gaddafi’s chest was a picture of the anticolonial leader Omar Al-Mukhtar (again wearing his glasses) in Italian captivity. What is more, during the visit he brought along Mukhtar’s elderly son.

With the start of the Libyan civil war on 17 February 2011, Al-Mukhtar’s picture was depicted on various flags and posters of the Free Libya movement and the rebel forces named one of their units the “Omar Mukhtar brigade”.

While at home and abroad the Libyan imam became an icon, bent to serve the political needs of various political factions, in the meantime what happened to Al-Mukhtar’s personal belongings?

In 1955 the Museo Coloniale of Rome received a formal request from the Libyan government for the return of Al-Mukhtar’s personal belongings, a request which apparently was ignored. In fact, still today, the eyeglasses of the Senussian leader are in the possession of the Museo delle Civiltà (MuCiv) in the EUR district in Rome, where the former colonial museum is stored in its warehouse (the Museo Coloniale is currently under construction and rearrangement, and is expected to open in 2021, under the controversial name “Museo Italo-Africano”).

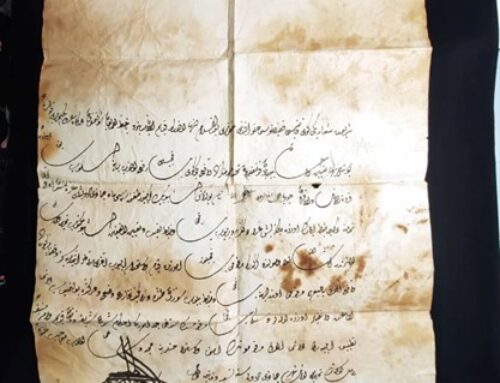

The story would end here were it not that a pair of glasses, exhibited as the authentic eyeglasses of the Senussian leader, are also on display in Tripoli at the Assaraya Alhamra Museum. The Assaraya Alhamra Museum, also known as the Red Castle Museum, is located in the historic building known as the Red Castle on the bay of Tripoli, and has its entrance in the historic Martyrs’ Square (former Piazza Italia). The museum was founded in 1919 by the Italians, who converted the castle that was originally used as an ammunition storehouse into Libya’s first big museum, to house some of the country’s countless archaeological artefacts. After Gaddafi’s coup d’état in 1969, a new wing was added, namely “The People’s Era Wing”, to document the Libyan struggle for independence (Falcucci, 2017). The new section commemorates some of the main figures of the Libyan resistance, displaying the personal belongings, photos and writings, among others, of Suleiman Al-Barouni and Omar Al-Mukhtar. Right there on display is a pair of old round eyeglasses, very similar to those worn by the leader of the Senussi in the photographs that portray him (Fig. 1).

Fig.1 Omar Al-Mukhtar’s glasses exhibited in the Assaraya Alhamra Museum

The eyeglasses are also featured in the aforementioned 1981 movie “The Lion of the Desert”, directed by Mustafa Akkad. In the movie, a young Gaddafi collects the imam’s glasses after his fall on the gallows; an anachronism, as Gaddafi was only born ten years after Al-Mukhtar’s execution. However, Gaddafi claimed many times that Al-Mukhtar was his childhood hero, and that his father, Abu Minyar, had fought under Al-Mukhtar against the Italians (though the latter claim is disputed, it can be corroborated by the fact that, like the Senussi leader, Gaddafi was also a member of a Murabtin tribe). Throughout his life, Gaddafi continued to represent himself as the heir of Omar Al-Mukhtar.

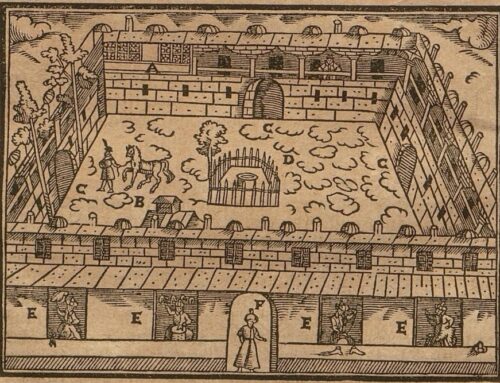

In 2015 a pair of eyeglasses, presented as belonging to Al-Mukhtar, appeared on the antiques market in Aleppo, Syria (Fig. 2). According to Abu Omar, the owner, they had been collected on the gallows in Suluq, where the Libyan resistance leader was executed, by a young student who had taken refuge in Syria to escape the Italian repression in Libya.

Fig. 2 Antique dealer Abu Omar in Aleppo (Getty Images)

During the eighteenth century, the display of “biographical objects” became popular entertainment: for example, Madame Tussaud made a common practice of displaying “biographical” objects, which were felt to “authenticate” the waxworks (Berridge, 2007). As a direct result of the eighteenth-century “culte des grands hommes” (Glover, 2000), during the Revolution objects, bodily remains, hair and ashes belonging to “great men” appeared in the first public museums in Paris.

The value of the glasses, and the fact that they belonged to a remarkable man, are never questioned by any of the actors at stake. However, Al-Mukhtar’s (many) eyeglasses (original or fake as they may be) take on a different value (sentimental, economic or political) depending on where and how they are exhibited. After all, the social construction of the relics’ value encompasses their trade (Geary, 1986), movement and politicization.

In the Museo Coloniale of Rome, the objects of Al-Mukhtar were exhibited like trophies, together with animal heads, the prizes of big game hunts. The very pictures of the elderly Libyan leader’s captivity suggest this same type of reflection: he is portrayed in chains, surrounded by Italian officers posing with him as they would have done with hunting prey. These photos are now “hidden” in a warehouse, away from the public eye.

On the contrary, the Red Castle Museum is a sanctuary of Libyan history, where the display of “relics” encourages devotion and veneration to the Libyan leader. Just like holy relics, these modern-day secular relics are not displayed for what they really are (a pair of eyeglasses) but for what they evoke (Al-Mukhtar’s legacy). The real value of such “divine” objects lies in their power as “advocates” for humankind to establish a connection with God: their authenticity is perhaps not so important, as they maintain their significance in the eyes of “believers” all the same. Therefore, just as the iconic holy relics of the True Cross of Jesus are claimed by many churches around the world, Al-Mukhtar’s glasses, difficult to verify as authentic, materialize in various places in the Mediterranean area, taking on different meanings on each occasion.

Beatrice Falcucci is a PhD candidate at the University of Florence, currently carrying out research on the colonial collections in Italian museums. She is author of “Il Museo di Storia Naturale di Tripoli, realtà contemporanea di un museo coloniale”, Museologia scientifica, 2017 and “Creating the Empire: The Colonial Collections of the Museo Agrario Tropicale in the Istituto Agricolo Coloniale Italiano of Florence”, Journal of the History of Collections, 2019. With Fausto Barbagli, she is author of the book Nello Puccioni. Affrica all’acqua di rose. Le missioni antropologiche in Cirenaica 1928-1929, Edizioni Polistampa, 2019.