The low clicking of the cicadas combines with the gentle lapping of the sea to block out all other noises. The canopy of Aleppo pines offers some much-needed shade on a hot June day. The bulk of the holidaymakers who boarded the ferry with me that morning in Cannes are now sunning themselves in one of the coves that dot the southern shore of the Ile Sainte Marguerite. Some might have briefly visited the island’s Fort Royal, best known as the place of incarceration of the mysterious Man in the Iron Mask immortalised in ink by Alexandre Dumas. Few, if any, will have made it to where I now find myself. The ticket vendor at the Fort was puzzled at my request for directions and Google Maps barely works out here on the island. No matter. This is a place best discovered in tranquil solitude. Amidst the encroaching vegetation, I can clearly see the carefully arranged lines of stones, each one marking the resting place of a North African once imprisoned on the island for their resistance to French colonial rule. Here, in the heart of France’s Cote d’Azur, these graves, numbering over 200, represent an unexpected and moving reminder of the geographies of repression and incarceration that shaped movement in the colonial Mediterranean.

Now a popular tourist spot, the Ile Saint-Marguerite once stood at the centre of the metaphorical, and indeed sometimes quite literal, carceral archipelago of the emergent French imperial state. The Fort Royal had served as a prison under the Ancien Régime, specifically used for the incarceration of Protestants following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes. In the wake of the French invasion of Algeria in 1830, the island’s vocation as a place of incarceration was renewed, this time with a specifically colonial dimension. The brutal campaign of military conquest pursued by the French in Algeria was met with fierce resistance by large swathes of the Algerian population. In the west of the territory, the charismatic Emir ‘Add Al-Qādir emerged as the leader of a counter-state that variously struggled against and sought to negotiate with the French military. To the east, Ahmed Bey, the Ottoman governor of the province of Constantine, led a concerted campaign of resistance to French encroachment on his territory. The first North African prisoners incarcerated on Ile Sainte-Marguerite would come from the ranks of these resistance movements.

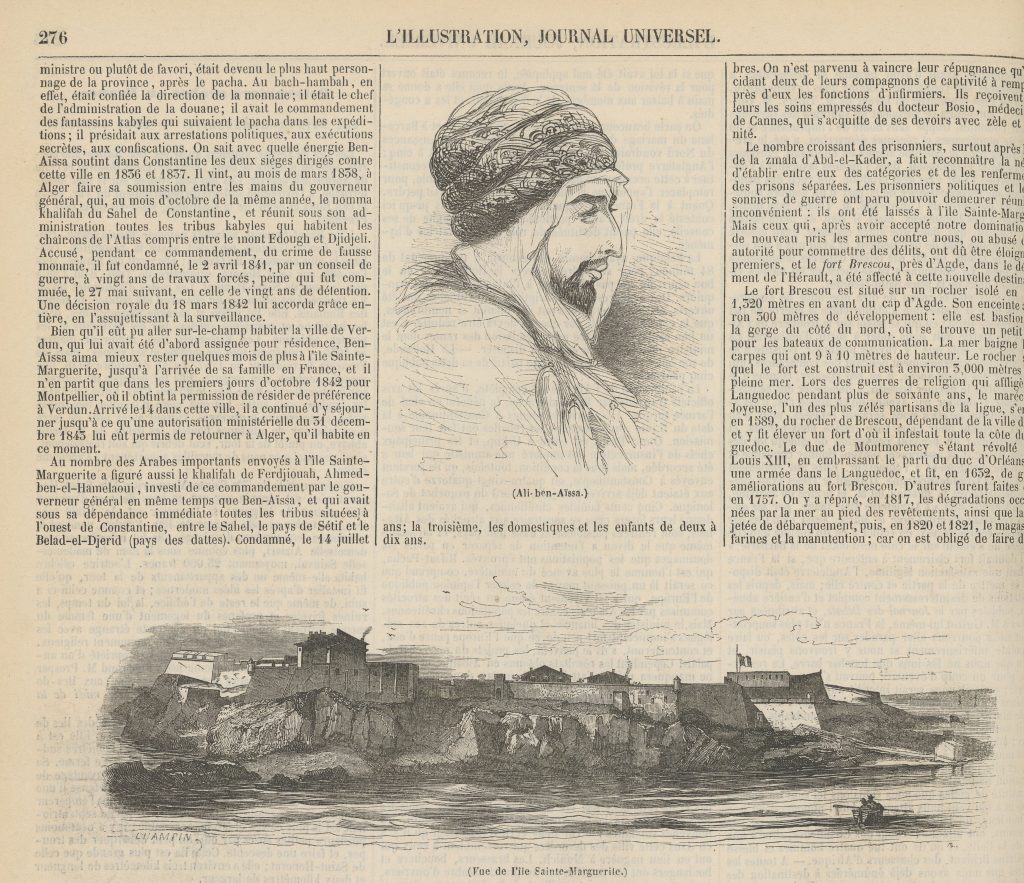

While the French authorities had begun deporting Algerians to the metropole for incarceration as early as 1836, it was in 1841 that the policy was officially instituted, and the Ile Sainte-Marguerite was designated for this purpose. The first prisoners arrived that year, including Ahmed Bey’s former leading general and administrator Ali Ben Aïssa, a prominent figure in the successful defeat of the French during the first siege of Constantine in 1836. Ben Aïssa had subsequently pledged allegiance to the French but, when he was accused of minting coins to support Ahmed Bey’s ongoing campaign of resistance, he was convicted of counterfeit and sentenced to 20 years hard labour and deportation to the metropole. Ben Aïssa’s case underlines the extent to which those imprisoned on the island, whether they were charged with explicitly political crimes (treason, sedition etc) or convicted for ordinary crimes (theft, forgery, assault), were primarily conceived of as a threat to the nascent colonial order in Algeria. (Figure 1)

Figure 1: L’Illustration: Journal Universel, No.70, 18/06/1844.

The numbers of prisoners detained on the island swelled dramatically in the wake of the defeat of ‘Abd Al-Qādir’s forces at the Battle of the Smala in May 1843. Over 300 men, women, and children captured in the Emir’s camp were deported to and detained on the island. This surge in the prisoner population led to a sharp decline in conditions, with the North African detainees suffering the consequences of overcrowding and poor diet. Efforts were made to improve the conditions of the prisoners, especially in the wake of the inspection visit of the noted colonial reformer and convert to Islam Ismaÿl Urbain in 1846-1847. Prisoners were ultimately allowed to leave the confines of the fort during the day and make use of the rest of the limited space on the island. They were allowed to prepare their own food, intermingle relatively freely and, when necessary, bury their own dead.

The numbers incarcerated on Ile Sainte-Margurite fluctuated for the rest of the period of the conquest. Historian Michel Renard estimates that the peak of the prisoner population was reached in April 1847, when 843 North Africans were detained there for a range of crimes related to their resistance to colonial rule. Even after the colony was formally “pacified” in 1847, the island continued to serve as a place of detention for those whose actions were considered a threat to the colonial order. Tribal leaders who resisted the encroachment of and expropriation by the expanding colonial state were joined in the prison by so-called “bandits” whose thefts of settler and/or military property were understood as acts of resistance by the colonial authorities themselves. The island continued to operate as a place of detention for North Africans until 1884.

The Ile Sainte-Marguerite was just one outpost of a much wider and constantly expanding network of penitentiary structures developed by the nascent colonial state in this period. Historian Sylvie Thénault has shown how the fortresses of France’s Mediterranean coast, including the island of Corsica, were increasingly deployed for the purposes of the incarceration of colonial prisoners from Algeria and subsequently Tunisia throughout the late 19th century. In the wake of the mass uprising against French rule in the Kabylia region of Algeria in 1871, the so-called Moqrani Revolt, a significant contingent of prisoners (around 250) were directed to the Fort Royal on Ile Saint-Marguerite. Others were sent much further afield, to penal colonies in French Guiana and, most famously, on the island of New Caledonia/Kanaky, where their descendants are living testaments to the broad and enduring reach both of the coercion of the carceral colonial state of the late 19th century and the resistance it provoked.

Of course, the coercive French colonial polity would continue to use a combination of detention and deportation to repress nationalist resistance in Algeria throughout the 20th century. The founder and first leader of the Algerian nationalist movement Messali Hadj spent much of his life either behind the bars of a French prison or in some form of forced exile, whether in remote regions of Algeria itself, small French provincial towns, a fortress on a French Atlantic island, or even a labour camp in the French colony of Congo. Many more foot-soldiers in the nationalist movement were imprisoned far away from their families either in labour camps in the harsh conditions of the Sahara or in the prisons of metropolitan France. Both restricting freedom of movement and forced displacement across, within and beyond the Mediterranean space were key coercive tools deployed by the French, and indeed other imperial powers in the region.

The community of prisoners established on the Ile Sainte-Marguerite constituted a micro-society, albeit one profoundly shaped and limited by the omnipresence of the coercive colonial state. Unlike the Emir ‘Abd al-Qādir and his extensive retinue, who were imprisoned in the castles of Pau and then Amboise on the French mainland, the prisoners of Ile Sainte-Marguerite had limited contact with the local French, though did live alongside a significant population of soldiers stationed in the fort. The colonial archive is largely indifferent to how these men, women, and children, built lives for themselves, conducted relationships within and beyond their communities and how they processed their experiences through their own cultural and religious structures of feeling. Fanny Colonna’s path-breaking work on North African prisoners in Corsica in the period shows the potential for thorough historical research to shine a new light on the lives of those incarcerated by the French colonial state in the Mediterranean but we have yet to see such a detailed study for the Ile Sainte-Marguerite.

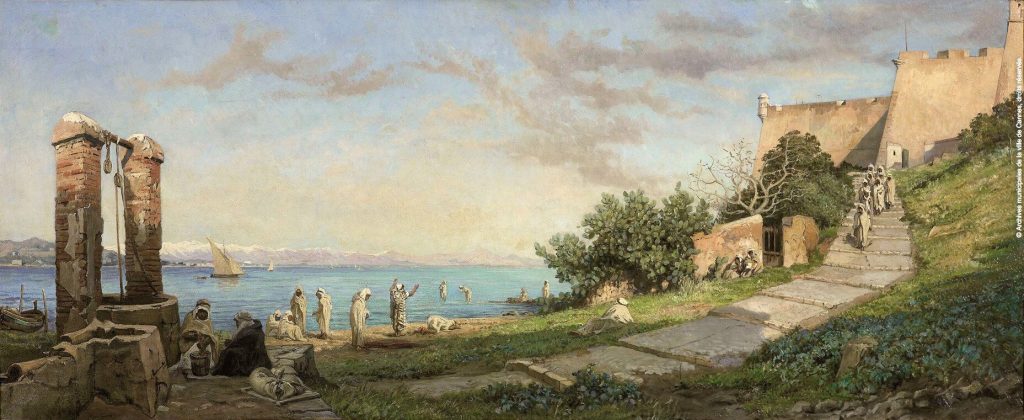

Instead, the prisoners appear to us today through the heavily mediated prisms of painting and photography, objects of display and subjects of imperial power whose agency has been negated. Incarcerated at the peak of the Orientalist craze, a trend that both reflected and reinforced the processes of Othering that underpinned colonial expansion, the prisoners of Ile Sainte-Marguerite soon attracted the attention of prominent French artists. Ernest Buttura, a Parisian painter who summered in Cannes, produced perhaps the best-known portrayal of the prisoners. His composition juxtaposed the familiar landscape of the Provencal coast with a simultaneously sanitised and exoticised image of the daily life of those incarcerated on the island. (Figure 2)

Figure 2: Ernest Battura, Prisonniers musulmans à l’île Sainte-Marguerite – Musée de la Castre, inv. 2006.0.69.

The work of the Orientalist painters like Buttura was somewhat mirrored in the mass production of photographic images of the North African detainees. The multiple postcards portraying the island’s prisoners are a point of intersection between the growing market for photography of “exotic” people and places in the Empire at the time and the expanding use of photography as a tool of legibility and disciplinarity for the coercive colonial state. Both the alterity and captivity of the North Africans was foregrounded to underline the power of the emergent French trans-Mediterranean imperial polity. (Figure 3)

Figure 3: Postcard of Tunisian prisoners on the Ile Sainte Marguerite, 1881, Photographer Jean Gilletta, Archives Municipales de Cannes.

This same objectifying gaze is replicated in the principal form of commemoration of the North African prisoners on the island today. In 1992, the French artist Jean Le Gac was commissioned to complete a series of murals on the walls of the cells in which prisoners from Algeria had been detained. While undoubtedly striking, Le Gac’s murals remain firmly within an Orientalist register. The Kiplingesque colonial administrators, the Bedouin fantasia, the inexplicable bare-breasted African woman and semi-naked North African “belly-dancer”, are far more a reflection of the artist’s racialised and gendered colonial imaginary than of the experiences of the North African men and women once imprisoned there. Ironically, this artistic intervention unintentionally exposes the persistence of an objectifying and sanitising discourse that minimises the violent nature of the colonial state, even here at a site of incarceration, and dehumanises the victims of colonial oppression. (Figures 4 and 5).

Figures 4 and 5: Murals painted by Jean Le Gac in the cells of the prison of the Royal Fort, photo taken by author.

And yet the cemetery, a largely abandoned space on the margins of the island’s official tourist trail, does speak to the dignity and humanity of those who lived and died far from their native land, simultaneously victims of and resisters against French colonial rule. It was the prisoners who ensured that their dead were buried in accordance with their religious traditions, it was they who created this sacred space for their community to honour those whose lives were curtailed by the violence of the colonial state. The neat rows of stones marking the resting place of those forcibly displaced across the Mediterranean is a poignant reminder that mobility in the Mare Nostrum has long been shaped by the coercive logics of colonialism. As I stand in silence by these untended graves, I cannot help but think of those among the descendants of these men and women who have found their own watery graves at the bottom of the Mediterranean, victims of the ever-evolving coercive apparatus of border regimes that are, at least partially, grounded in these same, enduring logics. Movement within, across, and between Mediterranean spaces remains restricted by and reflective of geographies of incarceration and repression.

Author Bio: Dónal Hassett is a colonial historian of the French Empire with a special interest in North Africa. A Lecturer in the French Department at University College Cork, he is also the Science Communication Officer for the PIMo COST Action. He is currently working on a project on a failed settlement scheme for Irish peasants in Eastern Algeria in the late 19th century.

Bibliography

Amiri, Linda, « Exil pénal et circulations forcées dans l’Empire colonial français », L’Année du Maghreb, 20, (2019), 59-76.

André, Marc and Slyomovics, Susan, « L’inévitable prison. Éléments introductifs à une étude du système carcéral en Algérie de la conquête coloniale à la gestion de son héritage aujourd’hui », L’Année du Maghreb, 20, (2019), 9-31.

Colonna, Fanny, La vie ailleurs : Des « Arabes » en Corse à la fin du XIXe siècle, (Actes Sud, Paris, 2015)

Thénault, Sylvie, « Une circulation transméditerranéenne forcée : l’internement d’Algériens en France au XIXe siècle », Criminocorpus [En ligne], Justice et détention politique, mis en ligne le 06 février 2015. DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/criminocorpus.2922

Renard, Michel, « L’île Sainte-Marguerite, un épisode oublié de l’histoire coloniale », 2019, http://islamenfrance.canalblog.com/archives/2019/05/04/37323551.html.

Yacono Xavier, « Les Prisonniers de la smala d’Abd el-Kader », Revue de l’Occident musulman et de la Méditerranée, n°15-16, (1973), 415-434.